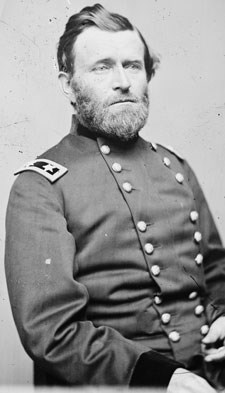

Library of Congress "It is hard on our men held in Southern prisons not to exchange them, but it is humanity to those left in the ranks to fight our battles. Every man we hold, when released on parole or otherwise, becomes an active soldier against us at once either directly or indirectly. If we commence a system of exchange which liberates all prisoners taken, we will have to fight on until the whole South is exterminated. If we hold those caught they amount to no more than dead men. At this particular time to release all rebel prisoners North would insure Sherman's defeat and would compromise our safety here." – General Ulysses S. Grant, August 18, 1864. This quote from General Grant is often cited as evidence that he stopped prisoner exchanges and that he did it because of the callous arithmetic of the war – calculating that by stopping exchanges the Union armies could simply outlast the Confederates. His statement is so ingrained into the common interpretation of Civil War prisons that it was engraved on the Wirz Monument in the town of Andersonville. However, the prisoner exchange issue was far more complicated, and the timeline of exchanges does not support the notion that Grant stopped the prisoner exchange.

Library of Congress

NPS/C. Barr Grant's statement was made in a different context. In the late summer of 1864, a year after the Dix-Hill Cartel was suspended, Confederate officials approached Union General Benjamin Butler about resuming the cartel and exchanges, including black prisoners. Butler, the Union Commissioner of Exchange, contacted Grant for guidance on the issue. Grant responded on August 18, 1864 with his now famous statement. In their conversation, Grant informed Butler that he approved an equal exchange of soldier for soldier, but did not approve a full resumption of the Dix-Hill Cartel. His issue was with the cartel's stipulation that the balance after equal exchanges were to be paroled and sent home to await formal exchange. By August 1864, Confederate prisoners far outnumbered Union prisoners, so a resumption of the cartel would release thousands more Confederates. Grant also felt that once released, Confederate prisoners would likely violate their paroles and rejoin their units. Many of the Union prisoners, on the other hand, had already fulfilled their enlistments and would likely go home. An agreement for resuming prisoner exchanges would not be reached until the winter of 1864-1865.

NPS Archival Image Even if exchanges were resumed in late August 1864, Andersonville would still be the deadliest prison of the war with some 8,000 dead by that time. It is therefore inaccurate to attribute the breakdown of the prisoner exchange and all of the sufferings of prisoners of war to a callous military directive by General Ulysses S. Grant. Although Grant was not responsible for the cessation of the Dix-Hill Cartel, he does bear a portion of the responsibility for the failure to resume the exchange. The United States government's policy was to halt the cartel until the Confederacy agreed to include black prisoners. When the Confederacy finally agreed to do so after more than a year, Grant failed to fulfill the Union's end of the agreement by refusing to fully resume the Dix-Hill Cartel as it existed in 1862-1863. |

Last updated: November 27, 2017