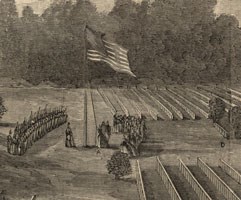

Library of Congress On August 17, 1865, a small ceremony was held in the newly established Andersonville National Cemetery. Clara Barton was given the honor of raising the American flag during this service, which also featured the playing of the Star Spangled Banner. Barton later claimed that the expedition to Andersonville was her idea, and the Harper's Ferry illustration of her raising the flag helped fuel this perception. However, the expedition to Andersonville was neither her idea, nor did she lead it.

Library of Congress On September 11, 1861, the War Department issued orders directing the U.S. Army Quartermaster General to assume responsibility for the burial and documentation of the nation's war dead. The first national cemeteries were established the next year in 1862. Between 1862 and 1871, the U.S. Army Quartermaster created 73 national cemeteries at battlefields, hospitals, and prison sites throughout the north and south. Many of these were established between April 1865 and 1871 as part of what was known as the Federal Reburial Program. Under this program, more than 300,000 American soldiers were moved into the cemeteries, although only around 58% were identified. Among these national cemeteries established by the US Army Quartermaster during the Federal Reburial Program was Andersonville. The establishment of Andersonville National Cemetery was not Barton's idea, and was planned as part of a larger program well before she became involved. The expedition to Andersonville was led by Captain James Moore, Assistant Quartermaster General, and he was a veteran of the cemetery system. Moore organized the burial efforts at Fort Stevens in 1864. In the summer of 1865 he was assigned to lead expeditions to the Wilderness & Spotsylvania, which he did in June, and to Andersonville, which he did in late July and early August. After leaving Andersonville, Moore was assigned the responsibility for all cemeteries and burials in Virginia. He also supervised the burial details at Antietam in preparation for the 5th anniversary of the battle. All total, Moore supervised the burial of more than 50,000 soldiers in cemeteries around the South. Moore and Barton bickered throughout the journey to and from Andersonville. For example, while staying in Augusta en route to the prison site, Barton complained that Moore refused to wait for her at dinner. Moore considered Barton a nuisance to the work, complaining, "Some people don't deserve to go anywhere. And what in hell does she want to go for?" The tension between the two combined with the popularity of Barton ensured that Barton's version of the story was what the public saw.

National Archives Barton's involvement in the Andersonville story began relatively late. At that time, the Army had no system in place to notify next of kin when a soldier died. Barton had already been visiting field hospitals and even battlefields to bring soldiers sorely needed supplies. By the spring of 1865, families from around the country were sending Barton letters asking for her help in finding missing loved ones who had gone off to war. Barton began publishing lists of missing soldiers in the newspapers. On June 22, 1865, Atwater wrote Barton a letter introducing himself and asking for a copy of her missing soldiers lists. He suggested that he could provide information on many of those listed. Barton then contacted Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and asked that she be given access to the Atwater lists, which by this point were in the possession of the Army and being copied. Granting her request for access, Stanton invited Barton to accompany the expedition, which left Washington, DC, on July 8, 1865. Arriving at Andersonville on the 25th, the team worked with members of 137th USCT out of Macon, GA, to physically replace the numbered boards in the cemetery with proper headboards that listed each soldier's name, rank, unit, and date of death. At Andersonville, Barton had access to the burial lists, and she spent much of her time responding to countless letters from loved ones. She also worked as a nurse for the work teams, several of whom became quite ill. Barton also spent a great deal of time meeting with area civilians, both black and white, discussing their thoughts about the prison and their plans for the future.

NPS/Eric Leonard You can learn more about Barton's work at Andersonville here. You can also learn more about her postwar efforts to identify soldiers at the Clara Barton's Missing Soldiers Office and her later work with the American Red Cross at Clara Barton National Historic Site. |

Last updated: November 27, 2017