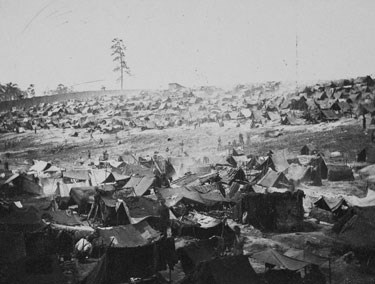

NPS/Andersonville National Historic Site In August of 1864, nearly 33,000 prisoners war were confined into an immensely crowded twenty-six acres. During this one month alone, approximately 3,000 died – an average of around 100 per day. This is the Andersonville as most people think about it and is depicted in film and literature. The only photographs taken of Andersonville show Andersonville in mid-August and its most crowded. However, many people are surprised to learn that for 10 of the 14 months the prison was open, it had a population well under 10,000 – its intended capacity. The first prisoners began arriving in late February and the prison population did not exceed 10,000 until May 1864. By mid-June the population hovered around 15,000 – overcrowded but manageable. The continuation of the Overland Campaign in Virginia combined with General Sherman's campaigns around Atlanta finally pushed to the prison site to its maximum occupancy in mid-August, when it held approximately 33,000 prisoners. However, this was a brief moment in Andersonville's operation. General Sherman captured Atlanta on September 2, and within days the Confederate command, concerned that Sherman would move to liberate the prison, began evacuating the stockade. Thousands of prisoners healthy enough to move were sent to prisons throughout the south, most notably Florence, SC; Salisbury, NC; and Savannah, GA. In less than a month, 25,000 prisoners were transferred and the prison population was a little more than 8,000. By November 1, the population had dwindled to 4,000. By mid-December there were as few as 2,000 prisoners at Camp Sumter and most of them were in the hospital – the stockade was virtually empty. The prison population spiked back up to a little more than 5,000 as some prisoners were evacuated from Savannah and Camp Lawton and returned to Andersonville in late December 1864 and early January 1865. From then until the end of the war the population declined as large scale exchanges resumed.

NPS/Andersonville National Historic Site The fall of 1864 through the spring of 1865 was a very different experience at Andersonville than during the summer of 1864. In an effort to differentiate the experience of prisoners in the fall and winter, one recent historian has even referred to this period as "The Second Andersonville." The decrease in numbers and the elimination of the overcrowding did not translate into an improvement in conditions, and death rates actually skyrocketed as the prison population declined. For example, of the 4,000 prisoners held in October, around 1,800 died – a death rate of 45%. Many people attribute the bulk of the problems at Andersonville to issues related to overcrowding, but suffering at Andersonville was far more complicated than that. The majority of the prisoners who died at Andersonville did so when the prison was much less crowded, and those that were held in the fall & winter of 1864 endured brutal cold without adequate blankets, coats, or access to firewood. For an account of Andersonville during these less crowded months you can read the recent published diary of Sgt. Lyle Adair, "They Have Left Us Here to Die" or the prisoner memoir of William B. Smith, "On Wheels and How I Came There" which is available online at http://archive.org/details/onwheelshowicame00smit |

Last updated: April 14, 2015