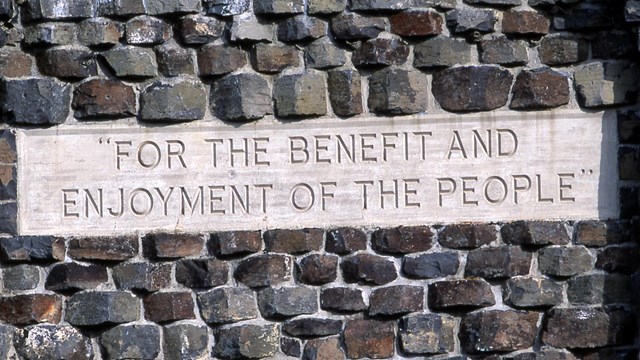

NPS / Thomas Moran, YELL 29 The crowning achievement of the returning expeditions was helping to save Yellowstone from private development. Langford and several of his companions promoted a bill in Washington in late 1871 and early 1872 that drew upon the precedent of the Yosemite Act of 1864, which reserved Yosemite Valley from settlement and entrusted it to the care of the state of California. To permanently close to settlement an expanse of the public domain the size of Yellowstone would depart from the established policy of transferring public lands to private ownership. But the wonders of Yellowstone—shown through Jackson’s photographs, Moran’s paintings, and Elliot’s sketches—had captured the imagination of Congress. Thanks to their reports, the United States Congress established Yellowstone National Park just six months after the Hayden Expedition. On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act into law. The world’s first national park was born. The Yellowstone National Park Protection Act says “the headwaters of the Yellowstone River … is hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale … and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” In an era of expansion, the federal government had the foresight to set aside land deemed too valuable in natural wonders to develop.

NPS Formative YearsThe park’s promoters envisioned Yellowstone National Park would exist at no expense to the government. Nathaniel P. Langford, member of the Washburn Expedition and advocate of the Yellowstone National Park Act, was appointed to the unpaid post of superintendent. (He earned his living elsewhere.) He entered the park at least twice during five years in office—as part of the 1872 Hayden Expedition and to evict a squatter in 1874. Langford did what he could without laws protecting wildlife and other natural features, and without money to build basic structures and hire law enforcement rangers. Political pressure forced Langford’s removal in 1877. Philetus W. Norris was appointed the second superintendent, and the next year, Congress authorized appropriations “to protect, preserve, and improve the Park.” Norris constructed roads, built a park headquarters at Mammoth Hot Springs, hired the first “gamekeeper,” and campaigned against hunters and vandals. Much of the primitive road system he laid out remains as the Grand Loop Road. Through constant exploration, Norris also added immensely to geographical knowledge of the park. Norris’s tenure occurred during an era of warfare between the United States and many Native American tribes. To reassure the public that they faced no threat from these conflicts, he promoted the idea that Native Americans shunned this area because they feared the hydrothermal features, especially the geysers. This idea belied evidence to the contrary, but the myth endured. Norris fell victim to political maneuvering and was removed from his post in 1882. He was succeeded by three ineffectual superintendents who could not protect the park. Even when ten assistant superintendents were authorized to act as police, they failed to stop the destruction of wildlife. Poachers, squatters, woodcutters, and vandals ravaged Yellowstone.

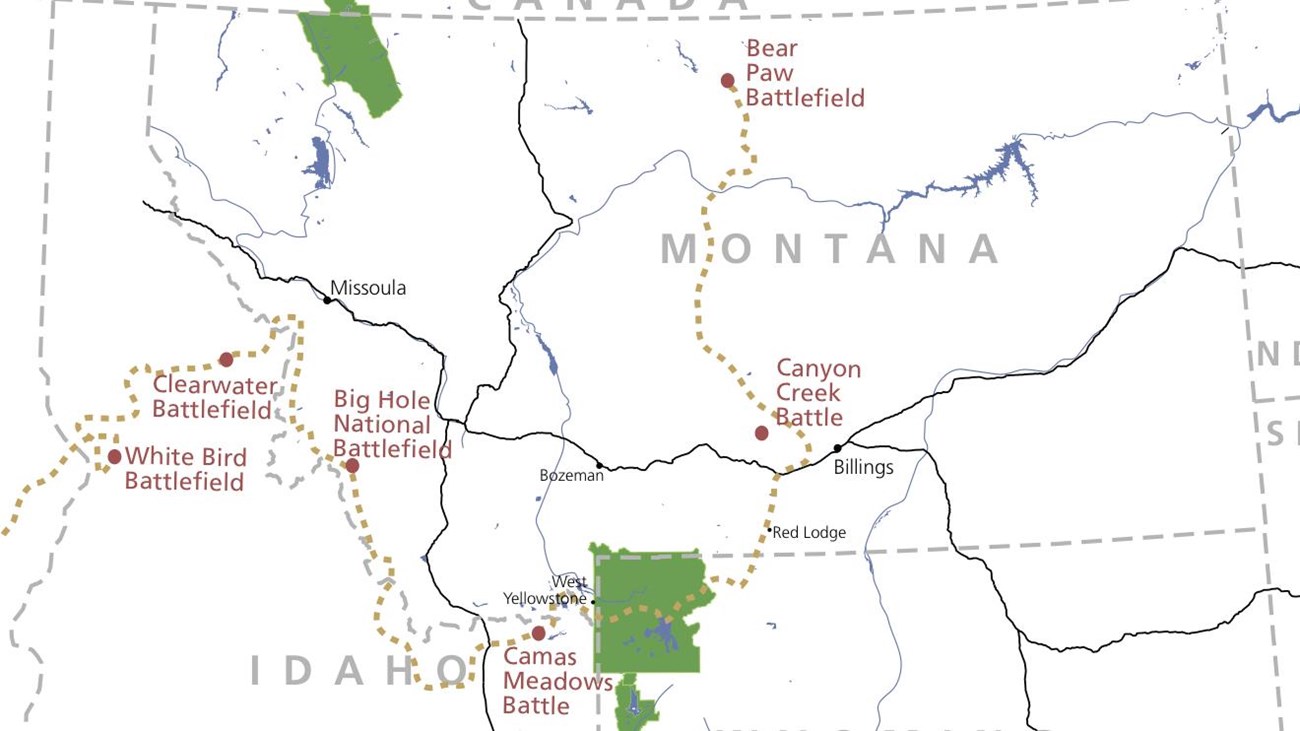

Flight of the Nez Perce (Nimi'ipu)

Summer 1877 brought tragedy to the Nez Perce (Nimi'ipu).

NPS The Army ArrivesIn 1886 Congress refused to appropriate money for ineffective administration.The Secretary of the Interior, under authority given by the Congress, called on the Secretary of War for assistance. On August 20, 1886, the US Army took charge of Yellowstone. The Army strengthened, posted, and enforced regulations in the park. Troops guarded the major attractions and evicted troublemakers, and cavalry patrolled the vast interior. The most persistent menace came from poachers, whose activities threatened to exterminate animals such as the bison. In 1894, soldiers arrested a man named Ed Howell for slaughtering bison in Pelican Valley. The maximum sentence possible was banishment from the park. Emerson Hough, a well-known journalist, was present at the arrest and wired his report to Forest & Stream, a popular magazine of the time. Its editor, renowned naturalist George Bird Grinnell, helped create a national outcry. Within two months Congress passed the National Park Protection Act, which increased the Army’s authority for protecting park treasures. (This law is known as the Lacey Act, and is the first of two laws with this name.) Running a park was not the Army’s usual line of work. The troops could protect the park and ensure access, but they could not fully satisfy the visitor’s desire for knowledge. Moreover, each of the 14 other national parks established in the late 1800s and early 1900s was separately administered, resulting in uneven management, inefficiency, and a lack of direction.

NPS The National Park Service BeginsNational parks clearly needed coordinated administration by professionals attuned to the special requirements of these preserves. The management of Yellowstone from 1872 through the early 1900s helped set the stage for the creation of an agency whose sole purpose was to manage the national parks. Promoters of this idea gathered support from influential journalists, railroads likely to profit from increased park tourism, and members of Congress. The National Park Service Organic Act was passed by Congress and approved by President Woodrow Wilson on August 25, 1916. Yellowstone’s first rangers, which included veterans of Army service in the park, became responsible for Yellowstone in 1918. The park’s first superintendent under the new National Park Service was Horace M. Albright, who served simultaneously as assistant to Stephen T. Mather, Director of the National Park Service. Albright established a management framework that guided administration of Yellowstone for decades.

NPS Boundary AdjustmentsAlmost as soon as the park was established, people began suggesting that the boundaries be revised to conform more closely to natural topographic features, such as the ridgeline of the Absaroka Range along the east boundary. Although these people had the ear of influential politicians, so did their opponents— which at one time included the United States Forest Service. Eventually a compromise was reached, and, in 1929, President Hoover signed the first bill changing the park’s boundaries: The northwest corner now included a significant area of petrified trees; the northeast corner was defined by the watershed of Pebble Creek; the eastern boundary included the headwaters of the Lamar River and part of the watershed of the Yellowstone River. (The Yellowstone’s headwaters remain outside the park in Bridger-Teton National Forest.) In 1932, President Hoover issued an executive order that added more than 7,000 acres between the north boundary and the Yellowstone River, west of Gardiner. These lands provided winter range for elk and other ungulates. Efforts to exploit the park also expanded during this time. Water users, from the town of Gardiner to the potato farmers of Idaho, wanted the park’s water. Proposals included damming the southwest corner of the park—the Bechler region. The failure of these schemes confirmed that Yellowstone’s wonders were so special that they should be forever preserved from exploitation.

Guidance for Protecting Yellowstone

Various legislation provides guidance for protecting Yellowstone National Park. World War IIWorld War II drew away employees, visitors, and money from all national parks, including Yellowstone. The money needed to maintain the park’s facilities, much less construct new ones, was directed to the war effort. Among other projects, the road from Old Faithful to Craig Pass was unfinished. Proposals again surfaced to use the park’s natural resources—this time in the war effort. As before, the park’s wonders were preserved. Visitation jumped as soon as the war ended. By 1948, park visitation reached one million people per year. The park’s budget did not keep pace, and the neglect of the war years quickly caught up with the park. Mission 66Neglected during World War II, the infrastructure in national parks continued to deteriorate as visitation soared afterward, leading to widespread complaints. In 1955, National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth persuaded Congress to fund an improvement program for completion by the National Park Service’s 50th anniversary in 1966. Although also designed to increase education programs and employee housing, Mission 66 focused mainly on visitor facilities and roads. Trained as an architect, Wirth encouraged the use of modern materials and prefabricated components to quickly and inexpensively construct low-maintenance buildings. This architectural style, which became known as Park Service Modern, was a deliberate departure from the picturesque, rustic buildings associated with national parks; their “fantasy land” quality was considered outmoded and too labor-intensive for the needed scale of construction. Mission 66 revitalized many national parks; in Yellowstone, intended to be the program’s showpiece, its legacy is still visible. It was a momentous chapter in the park’s history, and as the park continues to reflect changing ideas about how to enhance the visitor experience while protecting the natural and cultural resources, the question of how to preserve the story of Mission 66 is being addressed. Work in Yellowstone included the development of Canyon Village. Aging visitor use facilities were replaced with modernistic visitor use facilities designed to reflect American attitudes of the 1950s. Visitor services were arranged around a large parking plaza with small cabins a short distance away. The first Mission 66 project initiated by the National Park Service, Canyon Village opened in July 1957.

The Earliest Humans in Yellowstone

Human occupation of this area seems to follow environmental changes of the last 15,000 years.

Historic Tribes

Many tribes have a traditional connection to this region and its resources.

European Americans Arrive

In the late 1700s, fur traders traveled the Yellowstone River in search of Native Americans with whom to trade.

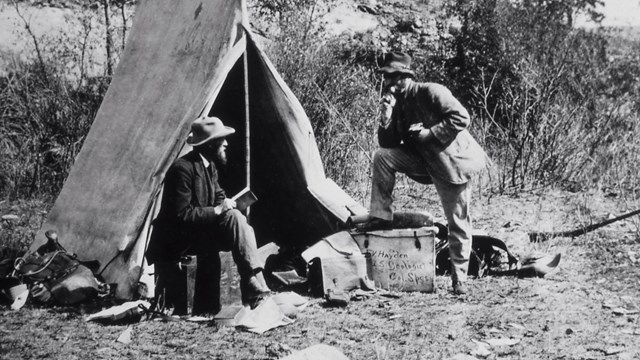

Expeditions Explore Yellowstone

Formal expeditions mapped and explored the area, leading to the nation's understanding of the region.

Timeline of Human History in Yellowstone

The human history of the Yellowstone region goes back more than 11,000 years.

Modern Management

Managing the national park has evolved over time and dealt with some complex issues.

Today's National Park Service

The National Park Service manages over 80 million acres in all 50 states, the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Guam, and American Samoa.

Park History

Learn about Yellowstone's story from the earliest humans to today. |

Last updated: September 22, 2025