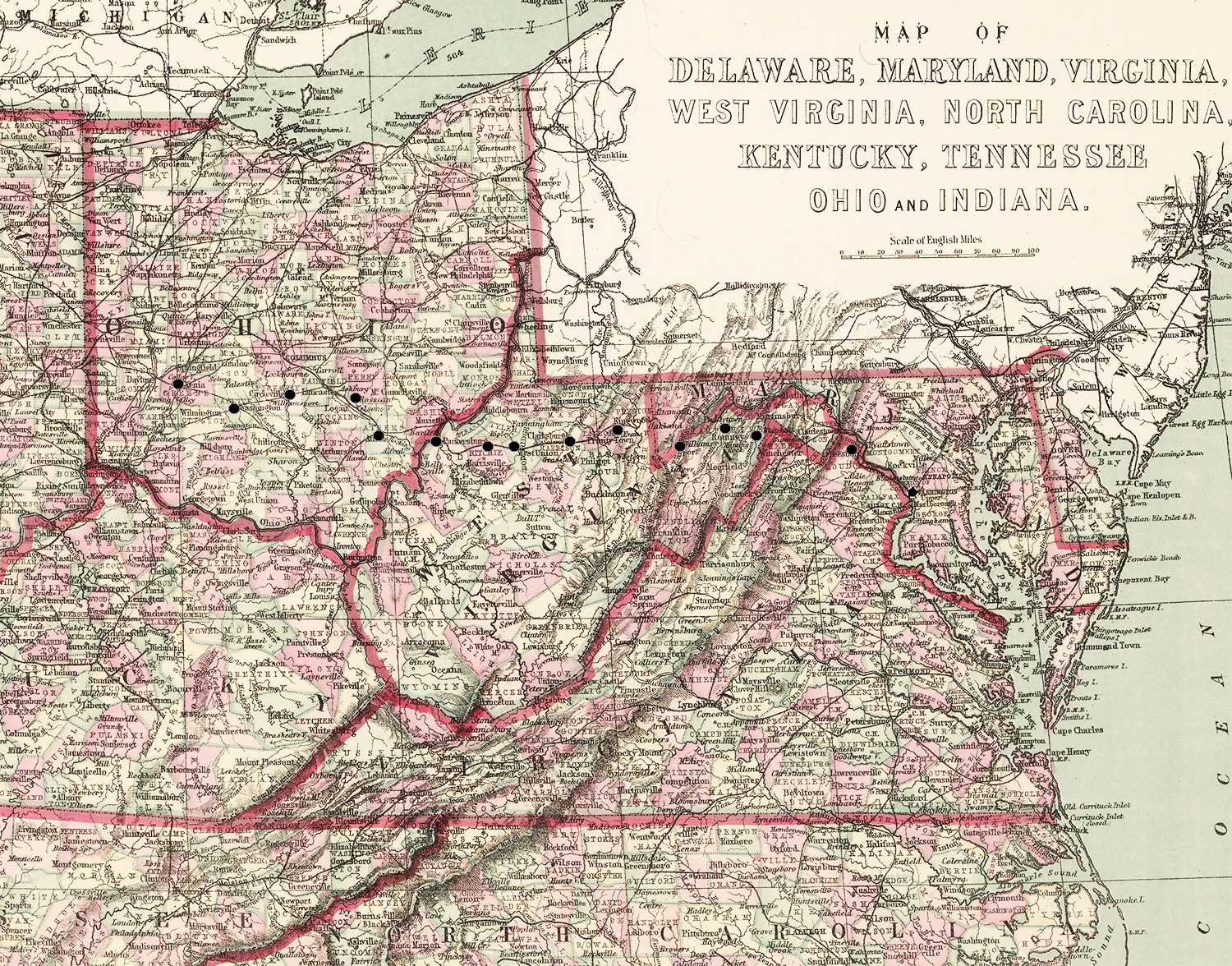

(Credit: Rumsey Map Collection & National Afro-American Museum & Cultural Center )

Contents

| Introduction

| Materials in the Lesson (Maps, Readings, Visual Evidence)

| Post-Lesson Activities

| Where it Fits Into the Curriculum (Objectives and Standards)

| More Resources

| About

What motivated African Americans to volunteer for a segregated military during WWI?

When the United States entered World War I, segregation was entrenched in military culture as well as civilian society. It put barriers up to prevent African Americans from enlisting. Despite this, about 380,000 African Americans served in the U.S. military during the war.

Colonel Charles Young was the highest-ranking African American Army officer in 1918. Despite an impressive leadership record, the Army refused Young’s request to command troops in Europe. Military leaders told him he was not healthy enough to serve.

To prove his fitness, Young made a difficult ride on horseback from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio to Washington, D.C. His brave display failed to persuade the Secretary of War. Young did not lead soldiers in Europe, but he fought for respect on the Homefront.

Materials Found in the Full Lesson

Accompanying Question Sets are paired with all materials in the Full Lesson (PDF).

Map 1: Map of the mid-Atlantic region showing Colonel Charles Young’s route with marked stops from Wilberforce, Ohio, to D.C.

• Text: Primary and secondary source readings provide content and spark critical analysis.

Reading 1: Essay, “Colonel Charles Young’s Biography and His Ride for Respect.”

Reading 2: Letter from Colonel Young, 1918, addressed to the Secretary of War.

Photo 1: The Colonel Charles Young House, 1910.

• Activity 1: “The First Draft of History”: News Reporting and the Historian’s Challenge

• Activity 2: Breaking Barriers to Military Service in American History.

• Activity 3: Buried But Not Forgotten: WWI History In A Local Cemetery

Where it Fits into the Curriculum

This lesson can be used in history and social studies curricula to cover topics related to civil rights and military service, African American history, World War I, and history investigations through local cemeteries.

Time Period: Late 19th and Early 20th Century through World War I.

Objectives

1. Describe how racism affected African American service men in the early 20th century and how Colonel Charles Young challenged it;

2. Develop and defend a theory to explain why men and women volunteer to serve in the Army;

3. Investigate, analyze, and report on one of three topics covered in an optional activity: 1) Bias in news reporting and its challenge for historians; 2) Civil rights and the U.S. military; 3) A local history investigation at a nearby cemetery to study WWI.

National Standards for History, Social Studies, and Common Core

• Standard 3A: The student understands social tensions and their consequences in the postwar era.

• Standard 2C: The student understands the impact at home and abroad of the United States involvement in World War I.

This lesson relates to Thematic Strands from the National Council for the Social Studies' National Standards:

• Theme II: Time, Continuity, and Change

• Theme III: People, Places, and Environments

• Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

• Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

This lesson relates to the Common Core Standards in History/Social Studies (6-8, 9-10, 10-11):

• CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.2

Craft and Structure

• CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.6

• CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.4

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

• CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.7

• CSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.9

Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity

• CSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.6-12.10

See the Full Lesson (PDF) for details about how the these Standards and Themes relate to the lesson. Search our Lesson Plans by National History Standards or Lesson Plans by Social Studies Standards to identify lessons that correspond with the eras and themes you want to teach.

The National Park Service manages the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument in Wilberforce Ohio, the historic home of Colonel Charles Young and his family. It is open to the public and offers a museum, guided ranger tours, and an archive. Click here to visit the Park website.

The National Park Service also offers a dedicated World War I online hub. This website provides visitors with links to related Park content, distance learning activities for all ages, engaging digital interactives, and rich historical and scientific content related to the "Great War." Click here to access these resources.

Ohio Historical Society

The Ohio History Connection website's The African American Experience in Ohio 1850-920 offers free access to over 100 primary sources from the life of Colonel Charles Young, including creative writing, military documents, and letters from family and individuals like W.E.B. Dubois, R.R. Moton, and Booker T. Washington. Young’s letters relate his own thoughts about experiencing racism, including racism in school and in the Army. Click here to visit the Charles Young archive.

The same collection of African American history includes the Ralph Tyler Collection. Tyler was an African American journalist and his articles that chronicle African American life during World War I. These articles can also be accessed free online here.

Ohio Memory

Another World War I lesson plan by Paul LaRue is available at the Ohio Memory website, along with several other teacher and classroom resources. Click here to access them or download his second lesson plan by clicking here.

The United States World War One Centennial Commission

The US WWI Centennial Commission's mission is in part to educate Americans about the World War. Its robust website provides teachers and facilitators with lessons, timelines, and interactives to support student exploration and curricula. Click here to access a searchable database of materials and reources on its website.

The Modernist Journal Project

Formed through a partnership between Brown University and the University of Tulsa, the project provides digitized copies of The Crisis, published between 1910 and 1922 by the NAACP. The collection is a treasure trove of information on African American World War I soldiers, including Colonel Charles Young. Other topics such as lynchings and civil rights issues are profiled. Click here to visit the Modernist Journals Project's Crisis series.

This lesson, Discover Colonel Young's Protest Ride for Equality and Country: A Lightning Lesson from Teaching with Historic Places, featuring the historic Colonel Charles Young House, is is based on the National Register of Historic Places nomination for the Colonel Charles Young House, also known as “Youngsholm.” Paul LaRue, a retired history teacher, and Sarah Nestor wrote this lesson, with editing assistance from National Park Service Historian Katie Orr and the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education staff in Washington, D.C. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Last updated: October 23, 2017