Sporting architecture was a unique feature of country house life in America. Playhouses, as they were generally known, were an entirely American tradition—the great houses of Europe have no equivalent. Typically, a playhouse might include a squash or tennis court, swimming pool, bowling alley, gymnasium, billiard room, or sauna. The playhouse reflects the enthusiasm for sport in America in the late nineteenth century. Embraced by the wealthy class, “manly sport” was seen as a means for combating the unhealthy environment of an office. The harder one worked, the more urgently he needed exercise. Architectural critics Harry Desmond and Herbert Croly observed in 1903 in their book Stately Homes in America: We Americans are too officious about our diversions, and the appropriate habitation for a contemporary house-party, far from consisting of a series of well-fashioned rooms, would consist rather of a casino with billiard and card tables, bowling-alleys, a tank, and a tennis-court as the chief items of equipment. The office and the play room symbolize the two characteristic and natural extremes of American life.

Casino was a term borrowed from the Renaissance meaning “pleasure house” and often applied to the playhouse. These buildings also included living rooms, bedrooms, dressing rooms, baths, kitchens, and servant quarters. McKim, Mead and White were the leading architects of such buildings and designed the sporting pavilion for the Vanderbilts at Hyde Park. Though modest compared to playhouses for other stately homes, the Vanderbilts’ sporting pavilion, called simply “The Pavilion,” was conceived in the same tradition. There was no accommodation for indoor sport here, but the location in proximity to the grass tennis lawn outdoors and a shower room denote the building’s intended purpose. Even the interior decoration symbolically perpetuated the idea of a sporting life.

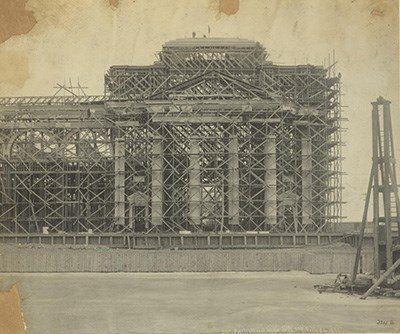

Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University. The Pavilion was the first new structure erected at Hyde Park shortly after the Vanderbilts purchased the property in May 1895. Design and construction of the new mansion would take nearly four years. But American millionaires were not known for their patience. Frederick and Louise’s desire to make use of the property immediately and observe progress on the estate necessitated the need for a livable space. Thus, the Pavilion was designed quickly, and built in just sixty-six days, facilitated in part by cost-effective solutions architects employed in the temporary architecture of the international world’s fairs. The Pavilion is constructed of wood, plaster, shingles, staff, and pebble dash. The structural strength of the Doric columns located at the east and west entrances of the Pavilion are actually pillars of brick concealed by fluted forms made of staff. Sometimes described as “counterfeit marble,” staff is a mixture of plaster, jute fibers, horsehair, and other ingredients. It was employed most notably to form the classical marble-like facades of the buildings at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle and Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Charles McKim, architct of the Pavilion, was among the principal architects that oversaw the building program of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Not only does the Pavilion reflect the materials used to create the exposition buildings, but also the neo-classical revival that followed in America for decades. The Pavilion is a compact, classical building that resides solidly on the landscape. It is composed of symmetrical east and west facades with centered projecting porticos supported by Doric columns. An open veranda was placed on the south elevation to balance the north and south wings. Later, by 1909, the veranda was enclosed with glazed panels to create a sun room. At the top of the Pavilion, the four gabled sides are united by a shingled attic surmounted by a balustrade. The exterior walls are finished in a rough course plaster called roughcast or pebbledash (lime mixed with cement, sand, small shells, and pebbles) and received a surface coating of limewash, a mixture of lime putty and water used as an architectural finish throughout the world for thousands of years. Inside, a two-story hall is paneled in oak at the first story level and surrounded by a second story open balcony. A large fireplace dominates the center of the south wall. A large 32-light brass chandelier is suspended from the ceiling beneath a circular laylight. Large mounted trophies of elk, buffalo and a ram decorate the walls. The room has the overall feel of the gentlemen’s lodges of the late nineteenth century. Surrounding the central hall, the first floor included a living room, bedroom, kitchen, scullery, pantry, a bath room, and shower room. A staircase hall on the north side of the hall provided access to six bedrooms (three of these for servants), a linen closet, a bath room, and lavatory. An additional bath room, likely for use by the servants, was located in the basement. Drawings for the Pavilion were completed in August 1895. Work began in September and was completed on November 24. An uncertain description of the Pavilion was published in the Poughkeepsie Sunday Courier on July 19, 1896: A bachelor’s lodge has been constructed, built on the site of the old carriage-house of which the general outlines have been carefully followed. The broad driveway of the carriage-house has been turned into the entrance hall of the Lodge. This contains an immense fireplace, and is to be used as the general assembly room, and lounging place. The furnishings of the lodge show traces of a feminine hand. The entrance hall is nearly covered with a large and beautiful rug. One may judge the size of the room when he learns that upon the rug stands a dining table ,a writing table, and a completely equipped card table. Around the room are scattered every variety of comfortable couch and lounging-chairs, making the hall the beau ideal of a bachelor’s headquarters. Opening off this hall on the north are small rooms, just the depth of the old stalls. On the north is the butler’s pantry, and beyond is the kitchen. Besides these there are on this floor several bath rooms, with eight curtain shower baths. The purpose of this building being to furnish free and easy accommodations for bachelor friends of Mr. Vanderbilt, the bath rooms are for their refreshment on coming in from golf or tennis, the kitchen appointments for the concoction of game suppers, and the main hall for smoking parties and story telling and gossip so dear to the masculine heart. There will no doubt be much merriment in this snug little pavilion in the time to come, but at present it wears the aspect of quiet domesticity, since Mrs. Vanderbilt has taken up her residence there in the dismantled condition of the Hall. Her rooms on the second floor, thought small, are brightened by a variety of exquisite feminine trifles. Carpets in plain color cover the floors, and the walls are beautifully decorated. A novel arrangement in curtains drapes the doors. It has always been a problem how to retain in a room the doors, which on often wants to close and still have the graceful effect of portieres. This is managed in the Vanderbilt cottage by a jointed curtain pole, which being fastened to the door itself opens and shuts with it. Drapery on another pole above the door conceals the upper moulding, and gives a dainty finish to the whole. On the other side of the door is hung another curtain so that when the door is open you still have the draped doorway. As the curtains are of the softest and richest kind, the effect is very charming. A gallery surrounds the large central hall, and from it opens the rooms in the second story. Above this one ascends by a narrow stairway to the roof, and here you step out through a veritable hatchway on what seems to be a veritable deck with gunwhale, canvas floor and all complete. It is easy to imagine a merry party of men gathered up here among the tops of the trees on a summer night for a comfortable smoke before turning in. The Vanderbilts utilized the Pavilion as their primary residence at Hyde Park until April of 1899. At the end of that month, furniture was moved into the completed mansion, where on May 12, 1899, the Vanderbilts entertained their first house party. From that time, the Pavilion functioned as intended, as a playhouse and bachelors lodge. The Vanderbilts stayed at the Pavilion on occasion in winter when the mansion was “put to bed” for the season. |

Last updated: November 6, 2024