NPS Photo The Vanderbilt Mansion is a home built expressly for the aristocratic lifestyle for a family whose name is the very definition of wealth and privilege. The children of William Henry Vanderbilt—at one time the wealthiest man in America—were the most prolific home builders of their era. The houses, often overbearing in their display of opulence, are a stark contrast to the stately house architects McKim, Mead & White designed for Frederick and Louise Vanderbilt at Hyde Park—an understated masterpiece of American design. By the time Frederick Vanderbilt purchased Hyde Park in 1895, it already possessed an appealing and illustrious history. Prior to Vanderbilt ownership, it was home to Dr. Samuel Bard (physician to George Washington during the American Revolution), David Hosack, the noted horticulturist, and the Langdon family, descendants of John Jacob Astor. Though members of elite, wealthy society, Frederick and Louise Vanderbilt lived graciously without spectacle. Hyde Park was a seasonal residence, one of a portfolio of homes the Vanderbilts owned in New York City, Bar Harbor, Newport, and the Adirondacks. Typical of the grand estates along the Hudson River, life at Hyde Park was rooted in the pleasures of the outdoors and genteel agrarian pursuits. House parties were leisurely and intimate, marked by games of golf or lawn tennis, carriage rides, and tea at neighboring estates. At Hyde Park, an extensive complex of greenhouses, formal gardens, and a model farm supplied flowers, produce, meats, and dairy for the Vanderbilt table wherever they were in residence.

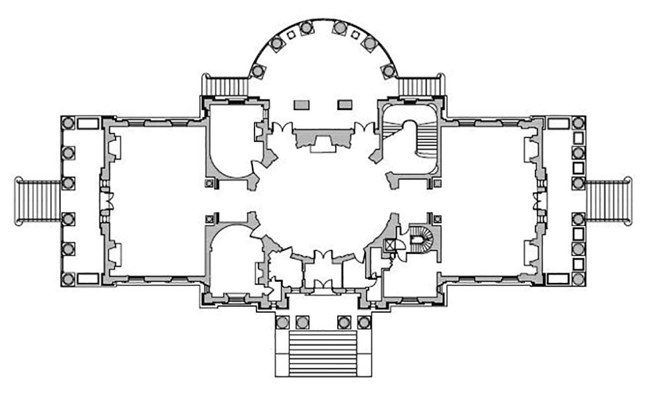

Charles Follen McKim (centre) with his business partners William Rutherford Mead (left) and Stanford White (right). The Vanderbilts’ selection of McKim, Mead & White, the leading architectural firm at the turn-of-the-century, is not surprising. The firm had designed numerous residences for New York society, but the house they design for Henry Villard on Madison Avenue in New York (1882-1886) marked a new era with emphasis on explicit high classicism—a style that would come to represent the extravagance and success of wealthy American capitalists. As the lead partner for the Vanderbilt commission, McKim’s, sober academic styling is evident at Hyde Park. Buildings by his architectural partner, Stanford White, displayed more relaxed, colorful interpretations of classicism. The architectural lines of new house built for the Vanderbilts was derived from the 1847 Langdon mansion that preceded it. Both houses exhibit the same classical concepts of simple blocks articulated by pilasters and a semicircular portico on the river facade. The new mansion, distinguished by its sturdy classicism, is grand, but not overwrought—a testament to McKim’s reserved use of classical vocabulary. The formal rooms of the ground floor are arranged in a concise, classical plan. A large living room and corresponding dining room accentuate the north and south end of the transverse axis. A series of subsidiary rooms—the reception room, the den, Mr. Vanderbilt’s office, and the grand staircase—are arranged around an elegant elliptical hall that provides access to the great semicircular portico overlooking the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains.

First floor plan. House for Frederick and Louise Vanderbilt, Hyde Park New York. McKim, Mead & White, Architects. Though modest compared to the grand houses of Vanderbilt’s siblings, the Hyde Park interiors spared no expense and are richly appointed with exotic wood paneling, imported marble, lush velvets, French tapestries, and, as was the custom, antique building components salvaged from the great houses of Europe. In the construction of Gilded Age country houses, prominent architects like McKim, Mead & White, generally collaborated with an interior decorator. The curious distinction of Hyde Park is that at least four decorating firms were independently and simultaneously at work on the design and execution of the interiors under the general supervision of McKim and the Vanderbilts—Georges Glaenzer, Herter Brothers, A. H. Davenport, and Ogden Codman. A further distinction is the rare overall carte blanche seemingly given McKim as chief architect on the design and furnishing of the ground floor reception rooms. Herter Brothers would carry out the architectural decoration of the entrance vestibule, the elliptical hall and the dining room and A. H. Davenport, the living room. Ogden Codman would design Louise Vanderbilt’s suite, and Georges Glaenzer would design Mr. Vanderbilt’s bedroom, his office, the den, and the reception room.

Dining Room, House for Frederick and Louise Vanderbilt, Hyde Park, New York. McKim, Mead & White Architects. NPS Photo. Mr. Vanderbilt wrote the firm placing the sum of $50,000 at the disposal of Stanford White to purchase articles of furniture and architectural salvage obtained in Europe. White’s acquisitions were guided by McKim’s wishes, a rare illustration of his aesthetic judgement, as well as a reflection of White’s effective decorating eye. McKim identified key furnishings for the hall, staircase, reception room, lobbies, dining room, living room and porticoes. In execution, the concept was followed with remarkable diligence. The local paper noted in mid-April 1899 that “Mr. and Mrs. Vanderbilt will shortly take up their residence in the handsome mansion.” On May 14, 1899, the paper reported that “Mr. and Mrs. F. W. Vanderbilt entertained a large party of guests who came by special train at their mansion on Friday last." Most likely, this was a reference to the Vanderbilts’ first house party at Hyde Park. Despite their overall delight with Hyde Park, the Vanderbilts were not entirely pleased with certain aspects of its design. They consulted interior decorators, including Jules Allard et Fils, about possible alterations, but as Frederick Vanderbilt explained in 1906, “so far the problem has not been solved to our satisfaction, and I fear will not be this time.” Rather than engaging McKim, Mead and White to undertake renovations, the Vanderbilts turned to another prominent New York architect, Whitney Warren, who had recently designed the New York Yacht Club and was then at work on Grand Central Terminal. Warren developed a scheme that would transform the halls on the first and second floors of the mansion and alter the living room. This was the only major change the Vanderbilts made to the house. Louise Vanderbilt died in 1926. In the years that followed, Frederick lived quietly at Hyde Park, maintaining the house much as it was left after Louise’s passing. Frederick died in 1938. Without children of his own, he left the house to Louise’s niece, Margaret Van Alen. At the suggestion of Vanderbilt’s neighbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Van Alen conveyed the house and furnishings along with 200 acres to the United States government. The house entered the National Park Service and was open to the public in 1940. It survives today in a remarkable state of preservation. |

Last updated: February 19, 2021