NPS/Irene Owsley Valles Caldera National Preserve has the honor of protecting and interpreting the resources, stories, and voices that represent at least 12,000 years of human history and influence on this landscape. Native American HeritageValles Caldera is of spiritual and ceremonial importance to numerous Native American peoples in the greater Southwest region. These cultural connections are both contemporary and of great antiquity, and the National Park Service respectfully seeks to uphold the values and prioritize the voices of the Tribes and Pueblos for whom this special place continues to be part of their practices, beliefs, identity, and history:

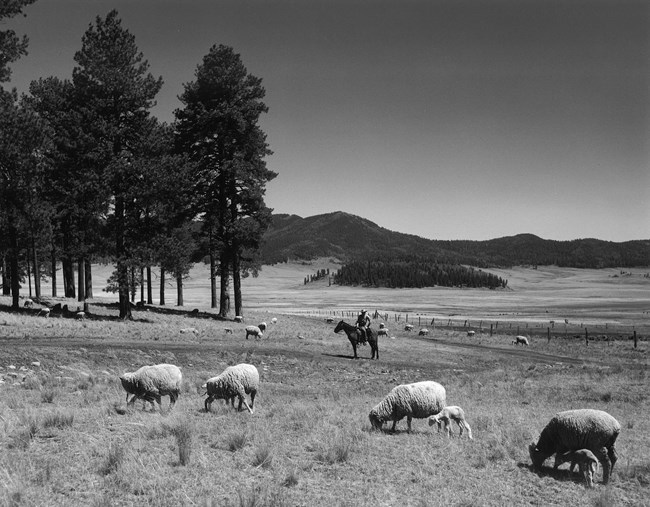

Paleo-Indian and Archaic Periods (10,000 BC - 1,000 AD)For most of the 12,000-year human history at Valles Caldera, people have interacted with this landscape in a nomadic and sustainable way. Before the adoption of agriculture, people lived in seasonal camps and villages as they moved across large territories in pursuit of food and favorable living conditions. Several small villages within Valles Caldera would have buzzed with activity during the summers as villagers spent their days hunting, fishing, foraging, and fashioning obsidian tools. They would move on to warmer climates during the long winter season, allowing seasonal periods of rest for the landscape. Pueblo Period (600s - 1600s AD)Starting around the 600s AD, people began practicing agriculture in the Jemez Mountains, leading to more permanent settlements called pueblos. The word “pueblo” can refer to a community of people (spelled with a capital “P”) or to the masonry structures that they built and occupied (lowercase “p”). Pueblos were often situated on flat mesa tops or near waterways that drained down from the mountains. Occupants farmed corn, beans, squash, and other crops to supplement their diets and sustain their communities. They continued hunting game and gathering plants for food, medicine, and ceremony. Pueblo runners traveled to and from Valles Caldera along traditional routes to procure important resources that only the mountains could provide. Every part of the Valles Caldera landscape was considered sacred, and it was treated as such. Many descendant Pueblo communities continue these traditional lifeways today. Spanish SettlementSpanish settlers began arriving in the 1500s, bringing sheep and other livestock to the montane grasslands of the Jemez Mountains. Sheepherding quickly became one of the primary uses of this landscape. We know very little about the Hispanic sheepherders who used this land, but most of what we do know comes from carvings they left on the trunks of aspen trees. These historic carvings are called dendroglyphs, and more than 3,000 of them have been documented by volunteers and historians at Valles Caldera National Preserve. By matching the names, dates, and towns from these dendroglyphs to U.S. census records, we can begin piecing together and preserving the histories of people who have otherwise been excluded from the historical record of this landscape. Can you decipher this dendroglyph?

Left image

Right image

Courtesy of Mary Ann Bond Bunten Private OwnershipValles Caldera also chronicles the history of New Mexico’s enchantment and exploitation—from 19th century land use after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and sheep grazing under the partido system to subsequent cattle grazing, timber harvesting, and geothermal exploration. Beginning as a land grant in 1860, private ownership was held by a series of four families. Cabeza de Baca (1860-1899)A decades-long legal battle over rights to a 500,000-acre Spanish land grant near Las Vegas, New Mexico, was resolved when the heirs of Luis Maria Cabeza de Baca offered to give up their claim to the land, provided they get an equivalent amount of land elsewhere. On June 21, 1860, the U.S. Congress authorized the heirs to select 5 equal-sized vacant tracts in the Territory of New Mexico. Their first choice was a 100,000-acre tract in the Jemez Mountains that became known as Baca Location No. 1. Otero (1899-1917)In 1875, Tomás Dolores (one of 40+ Cabeza de Baca heirs) mortgaged his claimed interest in the Baca Location to José Leandro Perea for $10,000. In 1890, Perea passed away, and his son-in-law, Mariano Otero, inherited his interest in the land grant. Otero and his uncle, Miguel Antonio Otero, had spent the past decade planning a commercial resort in nearby Jemez Springs, and this inheritance offered the possibility of expansion in the future. Mariano Otero and his son, Frederico (F.J.), immediately began buying additional interests in the Baca Location from other Baca heirs until finally, in 1899, Mariano Otero purchased the entire property. Bond (1917-1963)Redondo Development Company contracted with Frank Bond and his brother George W. Bond for the sale of the Baca Location in 1917, excepting and reserving all of the tract's timber and one half of its mineral resources for a period of 99 years. The Bond brothers expanded sheep grazing on the property through the partido system, which employed and exploited poor Hispanic workers from nearby communities like Cuba, Española, and San Ysidro. Learn more in the callout box above titled "Exploitation of Hispanic Workers: The Partido System." Dunigan (1963-2000)James Patrick Dunigan of the Dunigan Tool & Supply Company purchased the Baca Location in January of 1963 and established the Baca Land and Cattle Company. Despite his investors' wishes for the new acquisition, Dunigan was committed to maintaining a working cattle ranch and preserving the beauty of the landscape. He immediately sought to end the damaging logging practices that had decimated the property's forests since the 1930s, so in 1964, he sued the New Mexico Timber Company. Persistence paid off, as he was able to buy back the timber rights in 1971 and halt unsustainable logging practices forevermore. Public OwnershipValles Caldera TrustValles Caldera National Preserve was established on July 25, 2000, as an unprecedented national experiment in public land management through the creation of the Valles Caldera Trust. The Valles Caldera Trust was a wholly-owned government corporation overseen by a board of trustees appointed by the president of the United States. Through the Valles Caldera Trust, the U.S. Congress sought to evaluate the efficiency, economy, and effectiveness of decentralized public land management and ecosystem restoration. This 15-year experiment in public land management continues to contribute to the national dialogue on the role of protected areas for long-term economic and environmental sustainability along with innovative approaches to place-based and science-based adaptive management. National Park ServiceOn December 19, 2014, Valles Caldera National Preserve was designated as a unit of the national park system. After a brief transition period, the National Park Service assumed management of the preserve on October 1, 2015. As you explore the park, consider your place in the rich legacy of human travel to and through this landscape. The roads and trails you will follow here are likely the same routes that people have been using for thousands of years—from indigenous hunter-gatherers searching for obsidian sources to ancestral peoples procuring medicinal plants, Hispanic sheepherders leading their flocks to greener pastures, and American cowboys riding on horseback to secure the ranch perimeter.

|

Last updated: December 16, 2025