|

"It is certainly a most healthy life. How a man does sleep, and how he enjoys the coarse fare!"

Dickinson State University The Investment Theodore Roosevelt originally came to Dakota Territory in 1883 to hunt bison. The locals showed little interest in helping this eastern tenderfoot. The promise of quick cash, however, convinced Joe Ferris - a 25-year-old Canadian living in the Badlands - to act as Roosevelt's hunting guide. Through terrible weather and awful luck, Roosevelt showed a determination which surprised his exasperated hunting guide. Finding a bison proved difficult; most of the herds had been slaughtered in recent years by commercial hunters. When they were not sleeping outdoors, Roosevelt and Ferris used the small ranch cabin of Gregor Lang as a base camp. Evenings at Lang's ranch saw an exhausted Ferris falling asleep to conversations between Roosevelt and their host. Spirited debates on politics gave way to discussions about ranching, and Roosevelt became interested in raising cattle in the Badlands. Cattle ranching in Dakota was a boom business in the 1880s. With the northern plains recently devoid of bison, cattle were being driven north from Texas to feed on the nutritious grasses. The Northern Pacific Railroad offered a quick route to eastern markets without long drives that reduced the quality of the meat. Entrepreneurs like the Marquis de Morès were bringing money and infrastructure to the region. The opportunity struck Roosevelt as a sound business opportunity. With Roosevelt's interest sparked, he entered into business with his guide's brother, Sylvane Ferris, and Bill Merrifield, another Dakota cattleman. Roosevelt put down an initial investment of $14,000 - significantly more than his annual salary. Roosevelt returned to New York with instructions for Ferris and Merrifield to build the Maltese Cross Cabin. His investment was not purely for business; Roosevelt saw it as a chance to immerse himself in a western lifestyle he had long romanticized. As biographer Edmund Morris noted, “Fourteen thousand dollars was a small price to pay for so much freedom.”

Dickinson State University Return to New York After his successful bison hunt - the trophy head still hangs at Sagamore Hill - Roosevelt returned to New York. He showed characteristic vigor and force as he resumed his legislative duties in Albany, attacking corruption in government and making newspaper headlines in the process. He was earning greater approval and backing than ever before, and his political career was gaining traction. On February 12, 1884, a telegram arrived announcing the birth of his first child. Roosevelt felt on top of the world, enjoying toasts and congratulations from his colleagues. In his moment of joy, tragedy fell upon Theodore Roosevelt. A telegram arrived in Albany beseeching Roosevelt to quickly return to New York; his wife Alice and mother Mittie were both lying ill in the Roosevelt home. On Valentine’s Day 1884, Theodore Roosevelt sat by as his mother succumbed to typhoid fever. Hours later he was at the bedside of his wife as she died from kidney disease. Devastated, Roosevelt recorded in his diary a large "X" and wrote only a single sentence: “The light has gone out of my life.” Roosevelt dealt with his grief by immersing himself in work, laboring with single-minded fervor. He began to erase the memory of his beloved wife, destroying any correspondence that made reference to her, and never spoke of her again, even to their daughter. Roosevelt never looked back.

Dickinson State University Renewal When the legislative session ended in the late spring of 1884, Roosevelt turned his sights west. What was originally an adventurous business investment became an opportunity for escape. He traveled to his new Dakota ranch with the idea he might spend the remainder of his days as a cattleman. Despite the remoteness of the territory, Roosevelt found his Maltese Cross Ranch to be on a common route south out of Medora (the cabin was originally 7 miles south of the town). Seeking greater solitude, Roosevelt rode north down the Little Missouri River. He established a second ranch he named Elkhorn, about 35 miles north of Medora. With a new ranch came a new investment, and Roosevelt brought two trusted friends from Maine, Bill Sewall and Wilmot Dow, to manage his Elkhorn Ranch. The two woodsmen began construction on a new ranch house which would become Roosevelt's home in Dakota. Although he would actively participate in the life of a rancher, the Elkhorn was also a staging point for numerous hunting trips.

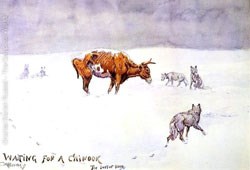

C.M. Russell Hunting and ranching in the west proved an effective medicine for the grieving politician. Over the next few years, Roosevelt would travel between New York and his Dakota ranches. Helping with a campaign in the fall of 1884, Roosevelt was back in Dakota by November to help form a regional stockmen's association to protect ranchers' interests. Spending the majority of the winter in New York, he returned to the Badlands in April 1885 for the spring roundup. The year 1885 saw Roosevelt publish his first of three books about his ranching and hunting experiences. Despite his youth and inexperience, the natural leader was elected chairman of the Little Missouri Stockmen's Association. Sometime late in the year, Roosevelt began to court his childhood sweetheart, Edith Carow. He reluctantly entered into a race for mayor of New York City in 1886 which he ultimately lost. Nevertheless, his thoughts of living as a rancher dwindled as his eastern life and career rekindled. The Badlands had lit a fire in a darkened soul. Disaster in the Badlands Roosevelt's book, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, prophesized that the cattle industry of the Badlands was unsustainable. Ranchmen flooded the plains with cattle, and with no regulation the region became overgrazed. Weather conditions throughout 1886 created a foreboding scenario. A late thaw and scorching summer meant a short growing season. Wildfires took their toll on certain areas, and by winter the cattle were underfed and ranchers had little feed to supply their livestock. The winter of 1886-87 proved to be extraordinarily harsh. One blizzard after another quickly buried what was left of the grazing land, and cattle were found “frozen to death where they stood” in temperatures as low as -41° F. Hardier cattle survived long enough to eat the tar-paper off the houses in Medora before succumbing to the elements. Others were found dead in trees after the snow melted, having climbed massive snowdrifts to reach the edible twigs before expiring amid the branches.

"Waiting for a Chinook" by C.M. Russell Tens of thousands of cattle died in the Badlands in the winter of 1886-1887, around 80% of the total population. In the spring, the Little Missouri swelled onto its floodplain, surging with melt water and ice. The carcasses of innumerable cattle bobbed down the icy river. Roosevelt had been abroad during the devastating winter with his new wife, Edith, and was unaware of the horrors until he returned to the U.S. in late March of 1887. Upon his return to Medora, Roosevelt found he had lost over half his herd. Where he once thought to see a return on his many investments, Roosevelt now sought to minimize his losses. He wrote his sister Bamie, "I am planning to get out of [the ranching business]." He would sell his interests in the Maltese Cross to his partners, and gradually divest himself of the Elkhorn. Although his ranch was used for numerous excursions and hunting trips, Roosevelt focused his energies on writing and politics. He finished selling off his Elkhorn interests by 1898. Legacy Although the ranching venture had spelled financial disaster for Roosevelt, the physically and psychologically transformative experience proved priceless. Roosevelt had sought to test his mettle and his manhood in an exceptionally rough part of the West, and had excelled in every degree possible. Always strong of mind and spirit, Roosevelt proved he was strong of body and soul. The skinny New York tenderfoot showed that he could work and live in the rough conditions of the frontier lifestyle. Largely sneered at upon his arrival in 1883, Roosevelt had grown to prominence, respect, and even admiration in the eyes of local people for his manner and conduct. Roosevelt carried with him an enthusiasm and genuineness that common people connected with, and this rapport was the foundation of Roosevelt’s later political success. His enthusiasm for cowboy life spurred him to form the Rough Riders, the notable cavalry unit that brought Roosevelt national recognition during the Spanish-American War.

NPS / Jeff Zylland Importantly, the cattle ranching collapse and his experiences in the wilderness began to solidify his conservation ethic, which became a cornerstone of his political career. The experience in Dakota had left an indelible mark on Roosevelt's heart, though he would not return often or for long periods after 1887. Roosevelt declared the Badlands as the place where "the romance of my life began," and they became as much a beloved part of his past as it was a stepping stone for his future. Visitors to the park today can experience the Badlands as Roosevelt did in his time, for the landscape is preserved as Roosevelt saw it. Whether one rides vigorously on horseback through the Badlands or relaxes in the shade of a cottonwood tree, they enjoy pastimes which registered deep in Roosevelt's heart. The same sights, sounds, and smells are experienced just as vividly as Roosevelt's writings. It was here that the need for conservation was born in Theodore Roosevelt's heart and mind, and the land here is preserved in his honor. |

Last updated: September 19, 2015