Diving in Isle Royale National Park

Isle Royale National Park occupies an entire island in Lake Superior, a wilderness area 45 miles long and two to six miles wide. It’s known for its wolf and moose, its rugged backpacking trails (there are no roads on the island), and its scenic forests, shores, and inland lakes. Though the park's founders did not have shipwreck preservation in mind when they created the park in 1931, they could have not designed a better underwater museum had they tried. It was once listed by a major U.S. sport-diving magazine as one of the top seven dive sites in the world.

Ten major shipwrecks lie in the waters surrounding the island, dating from some of the earliest steam navigation on the lake in the late 1800’s to the 1940’s. They include wooden and metal passenger-package freighters and bulk haulers, plus another dozen or so small craft built by local craftsmen-a sort of vernacular version of naval architecture as interesting as the larger ships to archaeologists and ship buffs.

The fresh, frigid, deep waters ensure spectacular preservation of organic remains on these sites. The wooden vessels have been pulled apart by storms, ice-heaving, and salvage tugs, but most of the metal steamers are virtually intact. The water below 50 feet deep never varies in temperature. It’s two degrees above freezing in mid-summer and remains two degrees above freezing under the ice during the long winter. Along much of the shoreline of the Archipelago, the ice stacks up in noisy, crusty piles grinding against the rocks until spring. Through this process, ice-gouging occurs as deep as 40 feet on some of the shipwreck sites we have studied.

BASICS

Location: Wilderness island in Lake Superior adjacent to Michigan, Minnesota, and Ontario

Elevation: 600 feet

Skill level: Intermediate to advanced

Access: Boat charter recommended

Dive support: Grand Portage, MN

Best time of year: Summer

Visibility: Moderate to excellent (30-70 feet)

Highlights: Historic shipwrecks

Concerns: Frigid waters, overhead environment, frequent storms, mouthpiece can freeze, some wrecks are deep

Rules and Regulations

DIVING TIPS

Dive with someone who is familiar with the area first.

Obtain diving brochures from the park staff at the ranger station. This park usually maintains an experienced cadre of divers and it is worth seeking their advice.

Consider purchasing Shipwrecks of Isle Royale National Park: The Archeological Survey. This is a popularized version of a major technical volume on the shipwrecks of the area that was generated by the National Park Service underwater team that both your authors are part of. We have no financial interest in its sale so we feel we can objectively recommend it. It will tell you all you will ever want to know-and a lot you won't want to know-about the Isle Royale ship wrecks.

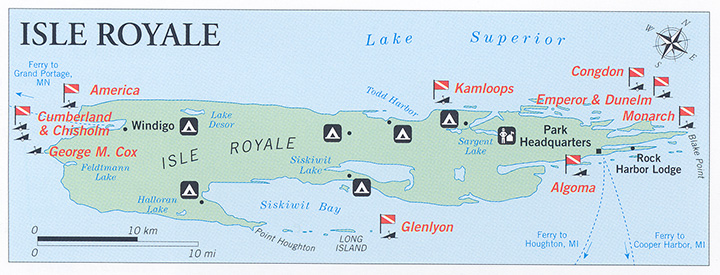

Dive Site Map

Dive Overview

In the shallower portions of some sites we find long stretches of scoured granite bottom. Streaks of red iron oxide stain the rock where metal ship structure has been dragged along the bottom by the heaving ice and rudely deposited as twisted piles of debris in deeper water. Bolts and rivets tom from the tortured metal are wedged in cracks in the basaltic lake bed. We feel as if we are visiting the scene of a violent crime when we return to the wrecks in May after the park's winter closure.

In stark contrast to the ice-tortured wrecks that lie in the shallows, is the pristine condition of those ghosts of a maritime past that lie in deep water and thus are spared the upheaval at the surface and preserved by the constant near-freezing temperature. Particles suspended in fresh cold water maintain a steady, shower cover in what seems a fantastical underwater theme park. Here, the massive anchors of a bulk freighter hang heavily from their chains in the hawse pipes; there on the bridge, the indicator on the telegraph is fixed to "finished with engines;" further down, rows of staterooms are furnished with bunks and mattresses that will never know the warm and weight of another tired voyager.

We experience a certain out-of-body sensation diving at Isle Royale. Weightless but bulky in our nylon or rubber dry suits, we can move with little effort as long as our movements are slow and deliberate. High performance breathing regulators deliver sufficient air, but it is thickened at depth and echoes loudly as it passes through the hoses and metal fittings. Frenetic movements or exertion in deep water can cause the mouthpiece to freeze at such low temperatures, resulting in a "free flow."

A frozen mouthpiece is a serious problem at Isle Royale, because cold air rushes in through the open regulator at such a force it can't be breathed. In the seconds it takes to remove the regulator, your entire oral cavity is numbed by the cold, so as an added inconvenience, you'll have no sensation in your mouth when you try to insert your backup regulator. It is akin to trying to play a clarinet on Novocaine.

The same factors of cold and depth that define our limitations also, however, enhance the otherworldliness of the experience. Absent here are the wood-boring teredo worms and most of the bacteria that attack the fabric of shipwrecks in warmer, saltwater environments, and the faintness of light at these depths further enhances preservation.

The oaken ribs or frames of wooden ship structure have so much integrity that we have bent ten-penny nails trying to pound them in for survey datum points. Leather boots are in thrift-shop condition except for the cotton thread that rots even in these superb preservation conditions. The shoes, seemingly sound, come apart when lifted from the bottom for inspection.

Probably the dominant sensation during a deep dive in this dark underworld is that of one's own body processes. Despite the effort to concentrate on tasks such as placing survey clips or taking measurements or observations we always find it hard not to fixate on the metabolic processes we take so much for granted on land. Chugging of heart, throbbing blood in temples, and loudest of all, rushing of air thickened by the increased pressure of the surrounding water.

No wreck in the park is closed to divers for safety reasons. Even on the Kamloops, which at over 200 feet, has been the scene of one fatality and one crippling injury, the NPS discourages, but doesn't prohibit diving. The same holds true for climbing El Capitan at Yosemite-there is no law that says you can't take risks in National Parks.

During the six summers the authors spent conducting a survey of the Isle Royale shipwreck, we gained more than information about a special collection of maritime relics. The scholarly process of melding the material record on the bottom of the lake to the written history of these ships was only one level on which our lives had been enriched by association with these sites. There was a less recognized but equally powerful value to the shipwrecks of Isle Royale. They were special places where those with the will and stamina could find touchstones to the past rarely equaled on land.

Diving in the Park

Your options are two: go with a charter dive operation or rent or bring your own boat. Some concessions at Isle Royale have been involved in the diving business at the archipelago for many years during which they have psyched out the logistics, weather, and underwater quirks of the park pretty well. It may not be a bad idea to make your first trip with these experienced folks, even if you want to strike out on your own later. In either case, remember it is required that you register at a ranger station before diving.

Just about all the diving at the park is focused on shipwrecks. The preservation is spectacular; the dives range from moderately serious to semi-suicidal.

Dive Sites

AMERICA

Probably the most popular dive at Isle Royale due to spectacular preservation, in comparatively shallow water (eight feet at the stem and 80 foot at the stern), easily accessible from Windigo, and sheltered from most wind exposure. A generally benign dive even for some penetration, but remember, the risk factor climbs the second you move into an overhead environment. One diver drowned on the America after becoming caught on the dogs (door latches) of the ship's pantry. (We had several more reports by divers of close calls on this door to what had, in the early 1980s, been dubbed the "forbidden room.") Members of the NPS Submerged Cultural Resources Unit team did some modification of historic fabric with a nine-foot pinch bar and the door is no longer a problem. There is a laminated map of this site for divers’ use available at the visitor center or from the dive charters. This should help in planning your dive and in understanding the wreck.

CUMBERLAND AND CHISHOLM

This site is composed of the remains of two wooden vessels both of which went down at the end of the 19th century. The 270-foot bulk freighter Henry Chisholm was built in 1880 and wrecked in 1898. You can cruise the disarticulated sides and floor of this ship in 20-40 feet of water. If you are observant, as you progress to the northeast, you will note that it becomes intermingled with the wreckage of another vessel, the Chisholm, which has a lighter, split-framed wooden structure. In about 80 feet of water you will find the Chisholm boiler and sections of paddlewheel from the sidewheeler Cumberland. One of the most exciting (and advanced) dives on the site is the engine of the Chisholm resting upright on its mounts and still attached by the drive shaft to its screw in 140 feet of water.

GEORGE M. COX

Not far from the mingled remains of Cumberland and Chisholm on Rock of Ages Reef is another large passenger steamer, this one metal. Built in 1901, the George M. Cox was sunk in 1933, the casualty of poor navigation in heavy fog at high speed. The 259-foot vessel hit a rock reef at such high speed that it slid over the reef and almost entirely out of the water. The skipper claimed he was doing 17 knots at the time of impact; day later he maintained it was 10 knots. If that sparks some interest, you can research the accident further in one of the publications on the island's shipwrecks.

Today the George M. Cox is in two major pieces and some minor ones with the bow in shallow water and the stern splayed open somewhat deeper. The site offers shallow diving (less than 20 feet) and continues down on a sharp angle to over 100 feet. The remains are interesting to compare with those of wooden vessels not far away.

EMPEROR

Built in 1910 and sunk in 1947, this huge bulk freighter is basically intact-about as intact as any vessel a diver is likely to see anywhere. It is so large that the bow and the stern are really two separate dives. The stern is the more exciting. You can swim through staterooms, see the engine, examine cargo holds. In fact, you can have many dives on this ship and still not poke into all the places that interest you. The rub is that dives on the stern run about 120 to 140 feet deep. This is cold water, the ship is easily penetrable, and it is deep--a recipe for both enjoyment and disaster. Unless you are really experienced and well-equipped for penetration, this is not the place to start experimenting.

KAMLOOPS

Many would not include this site because it is beyond any reasonable depth for sport diving. There is another standard, however, and that is technical diving. We herein note that the Kamloops is there and it is a great adventure, but we urge you not to dive it unless you are extraordinarily well-trained and experienced in wreck and deep, cold diving and are specifically equipped for it. With deep-freeze-like conditions and few visitors, the artifacts at this site are wonderfully preserved. Don't even think about removing them. Even if you're not caught you will have to live with the fact that you and others like you will have forced the park to close the site to further diving.

MONARCH

An easily accessed and, in our opinion, underrated dive site at Isle Royale. It is the only other major wooden vessel (aside from Cumberland and Chisholm) known at the island; a fascinating place to cruise about checking your understanding of marine architecture. Most of the site lies in less than 70 feet of water, and we find it a pleasant dive, well-suited for the second excursion of the day. This site, along with the others at Isle Royale, was mapped by the NPS SCRU team in the early 1980s. The first ever underwater trail guide for a shipwreck was created for this site in 1981. Feedback from visitors indicated that the plastic map was successful in bringing to life what before had been seen as "a jumble of timbers," but the plastic guide numbers we had placed on the wreck were seen as "intrusive to the ambience" of the site. Those remarks have been largely heeded in the last 15 years of NPS wreck management. It just goes to show that sometimes it's worth filling out those NPS visitor questionnaires.

GLENLYON

The remains of the Glenlyon may be found off the south side of Isle Royale near Menagerie Island in Siskiwit Bay. This area is often exposed to heavy weather but can be a great alternate focus of diving activity when the north side is taking a beating. A 328-foot steel bulk freighter, the Glenlyon was built in 1893 and sank in 1924. Although broken up and distributed over a large area now called Glenlyon Shoals, it makes a fascinating dive site. For some reason, the massive triple-expansion engine has assumed a position on the bottom allowing for particularly dramatic viewing. If you have ever seen the movie Alien, you may be reminded as we always are of the scene where the film's main characters visit the engine room of an ancient spaceship wreck.

ALGOMA

The only other wreck located on the south side of the island, the Algoma is a mediocre dive. The ship sank in 1885, claiming more lives than any other wreck in Lake Superior history, but unless you are seriously turned on by large spreads of twisted metal and artifacts covering many acres, this might not be the dive for you. For many years we joined others in looking for and hoping for discovery of the elusive bow of the Algoma. We now strongly suspect that the bow isn't missing at all, but is simply part of the underwater scrap heap which the Algoma has for all intents and purposes, become.

CHESTER CONGDON

Near the Emperor on Canoe Rocks, this is another monster bulk freighter that sank in 1918 not too far from where the former would end up 29 years later. The bow is broken off and faces up the opposite side of the reef from the stern. The dive is visually dramatic on the bow and entry is relatively safe. It sits on the rock reef at such a steep angle that most people who enter the pilot house undergo a slight attack of vertigo and tend to slide down the deck towards the stern. Some combination of visual and buoyancy phenomena causes this almost universal reaction. For those with a taste for irony, it is possible to take an interesting photo underneath the pilot house where on a broken bulkhead can be found a shipboard sign admonishing, "Safety first."

DIVING RULES AND REGULATIONS

All divers must register and Canadian divers must clear customs when they enter the park.

Diver-down flag must be displayed while divers are in the water. Both the red and white diver-down flag and the international blue and white alpha flag are acceptable.

No spearfishing

Removal of artifacts from the ships is strictly prohibited.

Use mooring buoys when provided (no more than three boats to a buoy). When buoys are not provided you may secure to a shipwreck by tie-off to a stable piece of wreckage. Do not drop anchors on the shipwrecks.

No diving is allowed in the inland waterways of the island on historic dock areas or in the Passage Island small boat cove. Compressor operation restricted to certain places and times.

Last Updated: October 31, 2012