Diving in Channel Islands National Park

Off the coast of Southern California lies a chain of islands, a string of gemstones set in a sparkling sea that can be seen from the mainland on a clear day. Only of few short hours from the Los Angeles megalopolis, these islands still reflect the natural beauty of coastal California 200 years ago. Sea lions frolic in the surf, elephant seals mate on sandy beaches, giant coreopsis plants bloom, and endangered brown pelicans are making a comeback. Offshore is a diver's paradise. Dense kelp forests provide habitat for a great variety of marine life.

The islands are set at the convergence of warm currents coming up the California coast from the tropics and colder currents pushing down from Alaska. Deep basins that produce an annual upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water from the ocean depths to the surface also surround them. This food-laced water, combined with the mixing of temperatures and the meeting of species from southern and northern ranges, accounts for great abundance and biological diversity of marine life. Of the eight Channel Islands, five are within the National Park: Santa Barbara, Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel. They lie offshore in a band parallel to the mainland and separated from it by the Santa Barbara Channel. Dry and desert brown most of the year, the islands turn lush and green after winter rains and offer a spectacular display of spring wildflowers. The volcanic out-croppings among the fields are steep and rugged.

The waters surrounding the islands are a mariner’s playground, offering sailing, kayaking, sportfishing, scuba diving, whale watching, surfing. The Channel Islands and the channel itself also support livelihoods such as commercial fishing, shipping and oil production. This national park is, in a way, a byproduct of oil production in the channel: pressure to protect these islands and their surrounding waters became intense in 1969 following an oil spill off the Santa Barbara coast. What had started as a land-based national monument in 1938 became a much larger national park in 1980. Today, with the associated National Marine Sanctuary, the park includes not just the five islands but also 1,252 square miles of surrounding water. On terra firma, visitors engage in hiking, camping, and tide pooling. Opportunities for the photographer, bird watcher, botanist, and wildlife enthusiast abound.

BASICS

Location: Islands off the coast of Southern California

Skill level: Intermediate to advanced

Access: Boat or shore

Dive support: Ventura, Santa Barbara

Best time of year: Summer and fall

Visibility: Poor to excellent

Highlights: Abundant marine life, kelp forest, shipwrecks

Concerns: Currents, surge, swells

Rules and Regulations

Dive Site Map

Dive Overview

Swimming through a kelp forest is a unique experience some divers prefer to that of drifting through tropical coral reefs. True, the diving is colder, but it is in colder water that kelp thrives, and so, in turn, does an abundance of other plants and animals that depend on kelp for survival. Water temperature at the islands typically ranges from 50-70°F, with the warmest water in the fall and coldest in the spring.

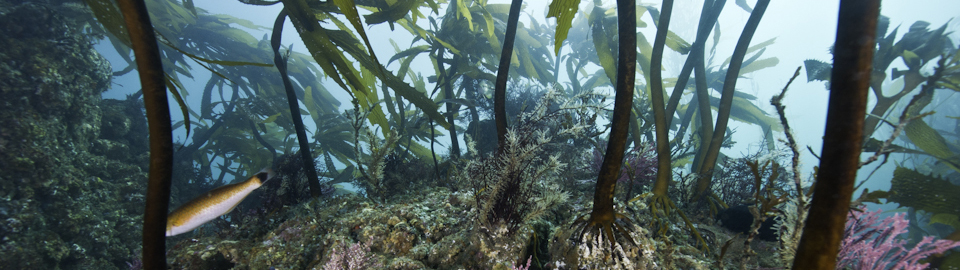

Diving in a kelp forest is a three-dimensional wilderness experience. It has been likened to hiking through a redwood forest, sans gravity. Imagine yourself hovering in the middle of the water column. Kelp rises above you to the surface where it spreads out in a thick canopy. The fronds are held afloat by gas-filled bladders. The sun's rays penetrate in shafts through crystal-blue water playing off fronds flowing gracefully in the current. Below are boulders covered with life on top of life, competing for space.

Under ideal conditions, giant kelp grows two feet a day. A type of brown algae, it is one of the fastest growing plant-like organisms on the planet. (Note for the amateur biologist: kelp actually belongs in neither the plant nor the animal kingdom. But for our purposes, we'll call it a plant.) It has no roots but attaches to a hard substrate such as rock by means of a "holdfast," which resembles a root ball in appearance. Thus the sight of kelp from the surface is a good indicator that there is a rock reef below. Different species live at different depths in a kelp forest, according to their particular needs for food and light, just as in any forest. You might see a snail clinging to a kelp frond, schools of bait-fish swimming near the surface, kelp bass suspended midwater, or a bright orange garibaldi standing guard over its nest in the rock reef. Abalone, scallops, and limpets cling to the rocks, lobsters probe with their antennae, and crabs scuttle with great purpose.

Between the southeast and the north-west ends of the park, a gradual change occurs in climate, conditions, and species typically found at each island. Santa Barbara, farthest to the south, offers the most tropical environment, followed by Anacapa, which is considerably farther north but also close to the mainland, in sheltered waters. These two islands, each approximately one square mile, generally offer warmer temperatures underwater and topside, clearer visibility, and calmer weather than islands to the north and west. The bright orange garibaldi, the official state saltwater fish, is a common sight in this area. A few are seen at Santa Cruz, but rarely further west.

Abalone are also picky about neighborhoods in which to settle. The pink and green species inhabit Santa Barbara and Anacapa, while red abalone inhabit Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel. Santa Cruz is the largest island, 21 miles long with 73 miles of coastline. It is a transition zone for many species.

The sites described in this book are only a minute sample of the diving the Channel Islands has to offer. A 479-mile coastline offers a variety of diving conditions, including current, poor visibility, surface chop, and surge, so be prepared for all of these. Nonetheless, in some places you can find sheltered areas with over 60 feet of visibility. Charter with a reputable sport diving operation is the best way to dive the park. Be prepared, as well, for stunning pinnacles and walls, historic shipwrecks, a vast array of marine life, and tantalizing kelp beds. Basking sharks, dolphin, and flying fish complete the experience as you journey across the channel to and from your dive destination.

ABOUT SAN MIGUEL

The cold waters of the California Current (which comes down from Alaska) reach the northwestern extremity of the channel, in the vicinity of San Miguel, and mix with upwelling water and currents coming up from the south. Of all the islands, San Miguel offers the most biodiversity.

Contributing to San Miguel's abundance is its weather. The predominant winds in the channel come from the northwest. Because wind and weather often prevent sport and commercial hunters from diving this island, resources have been better protected over time.

Don't let the climate dampen your enthusiasm for visiting San Miguel. A day calm enough to dive here is a rare opportunity that shouldn't be missed. If you own a drysuit, this is a good place to use it. Many species that are found in the Pacific Northwest also reside here: wolf eel, rockfish, and giant green anemones. No other place on earth hosts six species of pinnipeds in one location (four breed here); and 13 types of seabirds inhabit the Prince Island-Cuyler Harbor area. San Miguel is especially known for impressively decorated pinnacles that rise from great depths to the surface.

Dive Sites

WILSON ROCK

Surface current usually makes this an advanced dive. A narrow plateau approximately one mile long rises up steep from the surrounding water, which ranges in depth from 60 to 180 feet. Care must be taken when navigating in this area, as there are numerous breakers. The site lies two miles offshore from San Miguel. Wilson Rock is a conspicuous boulder, sitting 20 feet above sea level, conveniently situated to mark the site.

Depth along the top of the plateau is typically 20 feet, but the relief is dramatic, with canyons dropping down to 40 and 70 feet. As you venture over to the edges you will find yourself on a wall dive that rivals Little Cayman. The entire area is blanketed with tiny, orange and pink club tip anemones. They look like miniature Christmas lights. Be sure to take a light, or use flash with photography, to capture the splendid beauty and colors on display here.

Scallops the size of dinner plates grin at you with orange lips as you glide by, and myriad fish swarm through the area. Hydrocoral, a cold water coral, is found in pockets throughout the Channel Islands, including Wilson Rock. It may be either pink or purple. If you are lucky enough to encounter it, be careful with your fins. Like other coral, it is fragile and slow-growing.

Instead of the more common giant kelp, a different species of algae grows here at shallower depths. Eisenia, or southern sea palm, has a striking resemblance to a two-headed palm tree. It grows three feet high and then splits into two leafy pompoms at the top, swaying to and fro in the surge, further resembling a palm tree in a hurricane. This plant is well-adapted for intertidal areas with heavy surf. It has a thick, rubbery stipe (stalk) and a tenacious hold-fast, which provides a convenient handhold for a diver about to be swept across the bottom.

WYCKOFF LEDGE

The north side of all the islands is usually more exposed to weather. The south side of San Miguel, where Wyckoff Ledge is located, is considered the lee side. This high spot is a small plateau, rising to within 10 to 15 feet of the surface. The top is very pretty, with jumbled rocks, palm kelp, white spotted rose anemones, and lots of nudibranchs. It can surge if there is a swell. One side drops straight to 100 feet, touching down into sand. Visibility is often very good here.

Swim away from the drop-off and you will slide into 30 feet of rocky reef and dense kelp. Sometimes the kelp is so thick on this side of the island that it is noticeably darker underwater, but this is a sign of healthy habitat. It is far more difficult to swim through kelp on the surface than underwater, so remember to save extra air for the end of your dive to return to the boat.

A trained or patient eye may spot abalone grazing on the rocks. They are well-camouflaged, covered by the same growth of algae found on the reef. Giant kelp is a favorite food of abalone. If you spot one, try feeding it by gently sliding the edge of a kelp blade under its mantle. If it is hungry, and you are careful not to bump it and make your presence known, it may lift up slightly from the rock and draw the blade in under its foot.

Ubiquitous in San Miguel, rockfish also reside in this neighborhood, particularly the vermillion rockfish, often referred to locally and inaccurately as red snapper. Competing with abalone for food are sea urchins, whose sharp spines can poke like a needle.

TALCOTT SHOALS AND THE AGGI

Located off the northwestern tip of Santa Rosa Island, the shoal reaches from 70 feet to within 10 feet of the surface. The surrounding topography is mainly flat rock, with low-lying ledges and undercuts, ideal habitat for lobster and crab. Much of the terrain on the entire north side of the island is similar.

The shoal itself is a mile offshore, and may be best known for the Aggi, a 265-foot steel cargo ship that foundered onto the hidden reef in 1915 and remains draped across its rocks. The Aggi was under tow when a storm parted the towing cable. The three-masted full-rigged ship was carrying 3,100 tons of barley and beans. Today the wreck lies widely scattered in 20 to 60 feet, with large structural parts still recognizable. Regular rows of I-beams pattern the reef, and many of the apparent rocks in the area are suspiciously geometric in shape.

JOHNSON'S LEE

A large cove on the lee side of Santa Rosa Island provides an excellent anchorage with superb diving. Sand channels meander through high-relief reefs. Many species of plants and animals flourish here in this widespread kelp community: keyhole limpets, orange puffball sponges, stalked tunicates, bryozoa, scallops, abalone, lobster, crab, urchins, and solitary and schooling fish. Every square inch seems to be occupied. Because it is a safe anchorage, and there is so much life in any given location, this is a popular choice for night diving.

You can choose your depth at this site, which starts shallow near the beach and slopes downward toward open ocean. Sometimes conditions will influence your decision. A large swell, common during summer, can reduce visibility here, particularly close to shore, making the offshore sites more attractive. However, the area is also prone to strong currents which increase in velocity as you go farther out.

GULL ISLAND

Gull Island is similar to Johnson’s Lee in that it hosts a wide variety of marine life, offering a good representative sample of all that can be found at the Channel Islands. Located on the south side of Santa Cruz Island, earlier referred to as the transition zone, this site is almost dead center of the four northern islands.

Gull island is actually three small islands adjacent to each other, rising to 75 feet, and big enough to boast their own navigational light. This site encompasses a large area that offers first-rate diving: all around Gull Island itself; between Gull and Punta Arena (the nearest point on Santa Cruz, half a mile north); and west to Morse Point, one and a half miles away. The reef comes close to the surface in what mariners call a foul area, extending half a mile from Morse Point toward Gull Island, cascading into abundant reefs 15 to 30 feet deep and surrounded by kelp. Similar terrain lies between Gull and Punta Arena.

A quarter mile south of Gull Island, on the seaward perimeter, the depth slopes to 90 and 120 feet (then drops off to 1,200 feet). These large canyons are sparsely vegetated, but pleasing in their own way. Boulders provide good habitat for lobsters. Clusters of purple hydrocoral flourish here, as well as in shallower waters close to Gull Island. Amidst the busy reef life you may discover an octopus, camouflaged into the background, or slithering into a hole.

Excellent snorkeling is available if you meander through the large rocks that form Gull Island. Close encounters of the marine mammal kind are frequent throughout the area, as playful sea lions will pick you out for a little dive bombing practice. Visibility occasionally reaches a hundred feet here, so you can see them charging from a distance, or performing a graceful water ballet.

Gull Island is fairly exposed, and conditions can change quickly from docile to windy, surgy, and murky. Diving is often best in the mornings before winds pick up. Like Johnson's Lee, the area is subject to bouts of current. It is not diveable every day, but when the weather is calm it is pleasant and idyllic, with much to offer.

ANACAPA LANDING COVE

This Garden of Eden is protected from game harvesting within an ecological reserve, the long term effects of which are quite impressive. The cove is a time capsule, demonstrating what many places at the islands once looked like, and still would, if protected from the kind of exploitation that has diminished Gull Island.

Pink abalone are plump and abundant. Red urchins are the size of basketballs. Oversized lobster cram themselves into crevices, sometimes four "bugs" to a hole. Granddaddy kelp bass weave languidly through dense kelp plants, then disappear with a flick of the tail. The giant spined sea star really is a giant here. Colorful gorgonians adorn the reef in graceful fan shapes, and chestnut cowries decorate the bottom. Sun penetrates the canopy, and the water is often crystal-blue, making this a consistently beautiful dive.

All dive charter boats make stops here. You can also ride out to Anacapa on Island Packers, the park concessionaire, and dive this site from the dock, which runs along one side of the cove. Snorkelers, too, enjoy Anacapa. Many visitors to the island spend part of a day snorkeling the cove, where shallow water and good visibility make much of the scenery available from the surface. Snorkelers come here by tour boat, then suit up on the dock.

The dock is also where you'll see much action underwater: fish and other critters like to take up residence behind the pilings, so there is plenty of life to view. As you move out toward the open end of the cove the depth increases and the bottom gradually changes to sand, where other interesting creatures dwell.

If you stay along the wall opposite the dock and follow it toward open ocean, an impressive underwater arch starting in 30 to 40 feet will lead you from the reef and deposit you into the sandy habitat of 50 to 60 feet. Distant blue water is vignetted by the arch as you enter. Be sure to look up at the brilliant colors on the walls and ceiling as you go through, and bring a flashlight to enhance the experience!

The sand, barren at first glance, is a surprisingly busy place. Stop to watch the movements of a sand star, a sea pansy (looks like a lily pad), or a sea pen (looks like a quill pen). Halibut are seen lying in sand patches surrounded by reef, or swimming along the bottom, their flat bodies undulating like pancakes doing a dolphin kick. Diving the ecological reserve takes a little advance planning if you intend to fish or take game elsewhere. Not only is game-taking forbidden in the reserve, but possessing marine life in a reserve is also prohibited-even if it comes from outside the area. So if you plan to take fish or game, do so after you have visited the reserve.

Because the dock provides public access to the island, take precautions for boating traffic while diving here, especially during the summer. Have a flag up, look and listen before surfacing, and don't assume every boater will know what the flag means. Dive defensively.

WINFIELD SCOTT

Amidst the waving kelp close to the side of Anacapa, is the body, the corpus delicti of a ship-a wooden structure riddled with worms, iron machinery corroded and covered with marine growth. This is the watery grave of the Winfield Scott, a Gold Rush steamer that came to grief on this rocky shore in 1853. Divers occasionally find coins here, intermixed with pieces of brass. That the Park Service and Marine Sanctuary people are serious about protecting this area is evident from the major law enforcement operations they have run here in the last decade. One coin from this site cost a hardened vandal $100,000 dollars after he was caught by undercover park rangers.

CAT ROCK

Cat Rock on the south side of Anacapa offers pretty diving and interesting terrain. If this is your first dive of the day, explore the outer fringes of the reef that start at 70 feet and drop to 90 feet or more. If you arrive here later, stay closer to Anacapa Island and Cat Rock. Depths of 30 and 40 feet or less are equally enjoyable. High-relief topography and widespread kelp surround this landmark. You can expect good visibility, occasional current, and teeming reefs.

Cat Rock is one of several sites at Anacapa where giant black sea bass are being seen with increasing frequency. Only a few short years ago divers were unlikely to see these awesome creatures anywhere at the islands. They were reduced to near extinction from overfishing and incidental catch in gill nets, which are now illegal within a mile of the shore. It is an inspiring example of a comeback by a protected species. How will you know if you see one? Picture a Volkswagen swimming through the water. Giant sea bass can grow to seven feet long and weigh 500 pounds. If you are lucky enough to encounter one, stay still or approach slowly. They sometimes allow divers to get very close. It is a memorable experience.

SUTIL ISLAND

Sutil is located off the southwest corner of Santa Barbara Island and sits amidst spectacular diving. The relief is dramatic. The top of a reef may start at 20 feet, drop to 40 a short distance away, plummet to 90 feet, then skyrocket back to 50. The area is an endless series of walls, sand channels, canyons, and rocky plateaus. Kelp forests garnish the island waters.

Sutil Island is fairly exposed and there is often swell or current. By diving a little deeper you can usually escape the brunt of the surge. Plenty of enticing dive sites around Santa Barbara offer more protection, but Sutil is still worth the effort.

Temperatures above and below water hint at the tropics. It is often calm and sunny at Santa Barbara, and visibility of 100 feet is not uncommon. More southern ranging species are found here. You may see schools of white sea bass in the blue water beyond the drop-offs of Sutil in summer. Silhouetted bat rays swim gracefully overhead or bury themselves in the sand. Purple hydrocoral grows in isolated clusters around the island, and Santa Barbara hosts two pinniped rookeries. Sea lions breed off the southeastern slopes, and elephant seals haul out near Webster Point. This tiny island of one square mile, nearly 40 miles from the mainland, has more than its share of pristine diving.

DIVING RULES AND REGULATIONS

Diver-down flag must be displayed while divers are in the water.

Divers may not remove artifacts from park and sanctuary waters.

If you intend to spearfish or take game while in these waters, ask a ranger about California Fish & Game regulations, as they are extensive (these will be available from park rangers or local dive shops).

Last Updated: October 26, 2012

.jpg)

-Edit-2.jpg)