Contact Us

Beginnings: 1849 and 1861

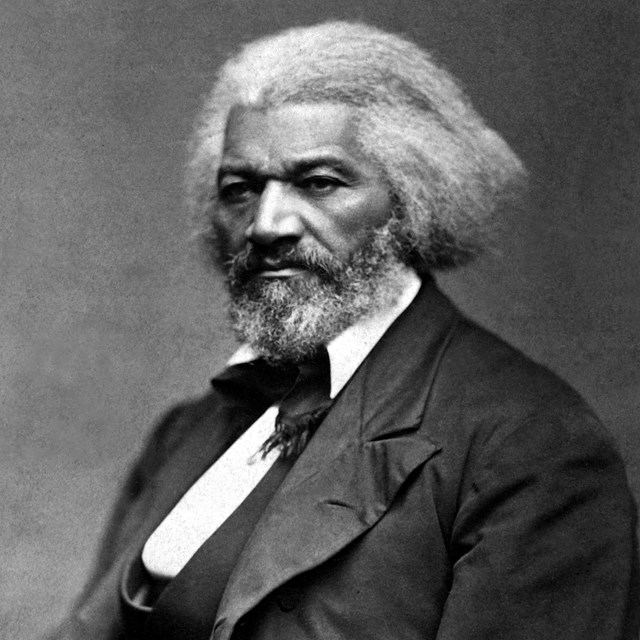

When Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony met in the late 1840s, he was one of the most well-known people in the United States and she was an unknown schoolteacher who had just quit her job because of unequal pay. Not long after, Frederick recruited Susan to be a lecturer with him in the Anti-Slavery Society and their friendship deepened.

Host: Ashley C. Ford

-

The Agitators Episode 1: Beginnings: 1849 and 1861

When Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony met in the late 1840s, he was one of the most well-known people in the United States and she was an unknown schoolteacher who had just quit her job because of unequal pay. Not long after, Frederick recruited Susan to be a lecturer with him in the Anti-Slavery Society and their friendship deepened.

- Credit / Author:

- WSCC, PRX, NPS

- Date created:

- 11/18/2020

ASHLEY C. FORD Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony’s fingerprints are all over The Constitution. Frederick Douglass – with the 13th and 14th Amendments – especially the 15th, which provided for Black men’s right to vote. Susan B. Anthony – with the 19th Amendment, which secured women’s right to vote. What most people don’t know is that Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony were lifelong friends. They had a rich, complicated 45-year-long friendship. They were allies. They were sometimes adversaries. They agitated each other. They agitated the nation. They had one of the most important and unlikely friendships in American history. I’m Ashley C. Ford. This is The Agitators. …. Presented by the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission the National Park Service and PRX.What you are about to hear over the next six episodes is a fiction based in facts.

What are the facts? That Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass met as adults and became lifelong friends. Fact. We know that their families were close. The Anthony’s were Quakers and abolitionists. On Sunday afternoons, local activists gathered at their family farm in Rochester, New York. The Douglass Family often attended. Before Frederick was close to Susan, he was especially close to Susan’s father – so much so that when Daniel Anthony died, Frederick gave the eulogy at his funeral.

We know that Frederick and Susan were both speakers for the Anti-Slavery Society.

We know, during Reconstruction after the Civil War, they were vital to the creation of the American Equal Rights Association – the AERA. We know they had a messy, public fight over the 15th Amendment – which, in 1870, prohibited voter discrimination based on race, but not sex -- effectively granting Black men the vote, yet still excluding all women. We’ll get more into that later. Frederick was, arguably, the foremost male feminist of the 19th Century. He routinely gave speeches at meetings for the National Woman Suffrage Association, which was founded by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In fact, on the day Frederick died – February 20th, 1895 – he had spent most of the day sitting next to Susan at a meeting of the National Council of Women – in Washington, D.C. And in that council meeting, on that particular day, there were women of color meeting alongside white women. But we know that the women’s suffrage movement too often excluded women of color– and this was a source of tension between Frederick and Susan.

These are the facts. We know Susan and Frederick were in the same place together at the same time with regularity for forty-some years.

What we don’t know is what Susan and Frederick said to each other behind closed doors. That is where playwright Mat Smart comes in. This six-part podcast is based on his play The Agitators which uses the facts of their friendship and. . . takes a leap.

2020 is the perfect year to reflect on these two American titans… it’s the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment and the 100th anniversary of the 19th. So let’s get to it.

Episode One: Beginnings. 1849 and 1861.

We begin our story in 1849, on the day that Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony met in Rochester, New York. Oh – one more thing – we know that Frederick taught himself how to play violin – and that he was good at it.

Prologue.

[In darkness, a breath. In. Out. In. A heart beats. Steady, then faster. Chains drag across a wooden floor. Chains fastened to a post. A whip lashes. It lashes again. Again. Again.] In silhouette, we see a tall, broad-shouldered man, with a brilliant mane of hair. He holds a violin. It is Frederick Douglass.

[He plays three short notes of the same pitch followed by a fourth on a lower pitch. The violin quiets the other noise. He plays the last note louder and louder until it loses tune. He pulls the bow from the strings. The sound of another lash. Another. The sound of the gag, the thumb-screw, the pillory, the bowie-knife. The violence of noise grows louder until it is unbearable. The violinist raises the bow and attacks the strings. He plays a few short, strong intervals. It quiets the other noise. The music from the violin is erratic. It has a melody for a moment and then the melody disappears. The violence of noise returns, gradually becoming louder than before. The man continues to play the violin along with it. Bloodhounds bark. A pistol fires once. Twice. The heartbeat and breath are deafening. A light rises on a tall woman with a piercing stare, some distance away. She watches the man play violin. The cacophony grows and grows until a string on the violin breaks.]

Frederick stares at his violin as though he does not understand what he holds in his hands

Episode One

The Anthony Family Farm Rochester, New York Autumn 1849

[A bright, Sunday afternoon. The lawn of the farmhouse. FREDERICK DOUGLASS, 31 years old, stands on the inside of a split-rail fence. Next to him, there is a chair and a tray of food. There is a dish of peach cobbler. It looks cold and untouched. SUSAN B. ANTHONY, 29 years old, watches him. FREDERICK takes out a pencil and hurriedly writes something down. He crosses a word out and writes another.]

SUSAN Mr. Douglass? Mr. Douglass? I cannot tell you how much I have looked forward to meeting you, Mr. Douglass. You are one of my father’s favorite people in Rochester. There is nothing he loves more than the Sunday afternoons you and your family spend here on our farm. And I apologize that my teaching in Canajoharie kept me away. It is an honor to finally meet you. But you have barely said a word all afternoon. Why are you out here by the fence, by yourself, in the far corner of the yard? And why have you not tried the peach cobbler I made? It is cold now. What were you playing? What song was that? Do you not like peaches? What did you write down? – a moment ago. You do not have to tell me, of course, but I am curious.

FREDERICK Here.

SUSAN “We have to do with the past only as we can make it. . . “

FREDERICK “Useful.”

SUSAN “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future.” “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future.” Thank you. I could not find good peaches in Canajoharie. Since I resigned my position, I have eaten a dozen peaches a day here. And I am not tired of them yet. I cannot believe you do not like peaches. I should have made an apple cobbler. Next Sunday, I will –

FREDERICK Did I say I do not like peaches?

SUSAN You did not say anything at all. Do you like peaches?

FREDERICK Yes.

SUSAN Oh. Then do you not like cobbler? I offended you earlier – is that what happened? I never should have stammered up to you and asked you to sign my copy of your autobiography. I apologize. Did I offend you earlier?

FREDERICK No.

SUSAN No?

FREDERICK No.

SUSAN Then I think you are being quite rude.

FREDERICK Rude?

SUSAN Yes, if I put you off earlier, then I apologize and I quite understand your behavior. But if I did not put you off, then I should think you are being rather rude.

FREDERICK You did not put me off earlier. You are putting me off now. I am here, in the far corner of the yard, because this is the best vantage point to watch my children play. To watch my beautiful wife Anna – with our little Annie swaddled to her chest. To watch your father and your mother, your brothers and your sisters. You. Look at all these abolitionists – young and old. Look at the miracle of our families all together. It is a glimpse of what the future of this hateful, hypocritical country could be. Outside this fence, a black man talking to an unmarried white woman is a death sentence. This conversation – right now – is enough to have me killed.

SUSAN You are safe here.

FREDERICK I am welcome here. But there is nowhere in America that I am safe. Charles! Down from the – Charles Remond Douglass! Down from that peach tree! You filthy abolitionist! Now! [From across the yard, the sound of children laughing]

SUSAN Outside this fence, the fact that I am 29 years old and unmarried is scandalous. Most women my age have six or seven children by now.

FREDERICK And why do you not?

SUSAN Oh, the question everyone must ask me! Do you too think I am incomplete without a husband and six or seven children?

FREDERICK It is not an indictment. It is only a question.

SUSAN As soon as a woman marries, she dissolves into her husband. All of the wages she earns go directly to him. She cannot purchase property. She cannot sign contracts. And if her husband drinks every night and beats her – she cannot divorce him. She cannot leave him. Because if she did, she would lose her children and be cast out from society forever. Her only prospects being prostitution and death. It is a wonder to me that any woman chooses to marry.

FREDERICK But what about love?

SUSAN How do you mean?

FREDERICK What if you fall in love?

SUSAN Who is to say I have not fallen in love?

FREDERICK I meant the general you – not you in particular. Because when one falls in love, sometimes it changes one’s thinking.

SUSAN Well, if and when one falls in love, it should not change one’s thinking on the injustices of the institution of marriage. . . . If I ever fall in love, it will be with an equal.

FREDERICK When I first met Anna, I was a slave and she was free. We were not equals. She was everything I hoped to become. Anna! You are a vision! – standing there with your violin – I love you! I have loved you since I first saw you in Baltimore walking down South Caroline Street! [FREDERICK picks up his violin and plays an impassioned riff] Do you hear how much I love you? [FREDERICK plays another riff. From across the lawn, the sound of his wife Anna playing her violin in response. FREDERICK listens. He smiles. He plays a riff, responding to her music. She responds to his. Together, they play a strange, rapturous duet. They finish with a flourish. From across the yard, there is clapping and a burst of approval] I owe everything to you – you beautiful, euphonious woman! [The children laugh; quietly, to SUSAN, still looking at Anna] I only had the courage to run away because I was running away to Anna. Twelve days after I escaped, we were married. Throughout my life, it is women who have taught me how to be the man I am. Your father said you recently gave your first public speech in Canajoharie – a speech on temperance. He said it caused quite an agitation.

SUSAN Agitation is overstating it. It was more of a. . . stir. A gentle stirring really.

FREDERICK It prompted people to start calling you “The Smartest Woman in Canajoharie.”

SUSAN I am afraid that is not much of a compliment. [FREDERICK laughs] And more accurately, people called me “The Smartest Woman Who Has Ever Been in Canajoharie.” Sadly, still not much of a compliment.

FREDERICK Your father beams with pride when he speaks of you.

SUSAN I do not know why. I am a school teacher who quit her job and moved home. I have done nothing yet.

FREDERICK He believes you can become anything you want to become. . . . Do you realize how unusual your father is?

SUSAN He is like many Quaker men.

FREDERICK No, he is not. Even though Quaker men say they believe in the equality of the sexes, when it comes to their wife – or daughter – speaking her mind with abandon – their conviction wanes. It may be 1849, but most men, however enlightened, find the idea of a woman giving a public speech repugnant.

SUSAN And how do you find it?

FREDERICK I find it. . . as vital as oxygen. It is a pleasure to finally meet you. SUSAN And to meet you.

FREDERICK Please – sit.

SUSAN No, thank you.

FREDERICK Sit for a moment – I insist.

SUSAN I do not know how to sit. May I tell you why I resigned my teaching position in Canajoharie? It is because I cannot sleep. I lie awake at night, my mind racing, my heart pounding – only thinking of one thing: How do we end slavery? How? Mr. Douglass, what can I do to help? I know there are many things that my father – and all of my family – have already tried, but nothing has changed. What more can we do? It is 1849 – how is this still happening? I cannot think of anything else. I cannot sleep. I –

FREDERICK So we should end slavery because it keeps you up at night?

SUSAN That is not what I –

FREDERICK Why then? When is your birthday?

SUSAN What?

FREDERICK When were you born?

SUSAN February 15th, 1820.

FREDERICK I do not know mine. Not the day. Not the year. Do you keep a record of a horse’s birthday? Or a mule? I did not understand – when I was growing up – why did the white children get to have birthdays and I did not? Why do you get to have a birthday and I do not? Answer that. Why? [SUSAN tries to find an answer, but she cannot] Slavery is not an idea to me – it is not a great evil that happens far away in the South that keeps me up at night. Slavery is what stole the first twenty years of my life. Why do you get to know your brothers and sisters and I do not? Because mine are in chains – right now – my sisters and my only brother are in chains right now – And three million of my brethren. Has your father ever hit you?

SUSAN What? – no.

FREDERICK Has he ever whipped you?

SUSAN No.

FREDERICK Has he raped your mother?

SUSAN Mr. Douglass!

FREDERICK That is what the white man – my father – did. That is what the white master did to my mother. Over and over. Slavery steals our bodies away from us. It is a destroyer of family. My daughter Rosetta was born June the 24th. Lewis on October 9th. Frederick – March 3rd. Charles – October 21. Annie – March 22nd. They are why slavery must end. . . . What I would give – to have known my mother. What I would give – to look across the yard on a Sunday afternoon and see her. I only saw my mother but four or five times in my life. After I was born – she was taken from me and put twelve miles away. But four or five times, at night, she was able to walk the twelve miles and lie down with me and sing me to sleep. And long before I waked, she would be gone. She had to walk the twelve miles again before daybreak or she would be whipped. She worked sun-up to sun-down, walked twelve miles, sang me to sleep, then walked twelve miles back before sun-up. And I – I cannot remember the song. [FREDERICK hums three short notes of the same pitch followed by a fourth on a lower pitch] It is always just out of reach, just beyond. But I will find it. I will find my mother’s song.

[FREDERICK picks up his violin and plays. On his violin, FREDERICK plays the three shorts notes of the same pitch followed by a fourth on a lower pitch. He cannot remember any more. He plays the four notes again. He plays it again. He cannot remember it]

SUSAN What can I do to help?

FREDERICK There is only one thing to do. To agitate. Agitate, agitate, agitate.

SUSAN But agitation alone is not enough.

FREDERICK Agitation is the spark to the fire of all change. As long as there is slavery, the Constitution is a sham. It is nothing but a piece of paper with lies and unfulfilled promise. We must make people angry, make them listen, make them talk. Nothing changes if people are not talking about it. That must come first.

SUSAN We need more than words.

FREDERICK Why is it illegal to teach a slave to read? Because words can shine light unto injustice like no other force. If I did not know how to read and write, I never could have escaped slavery. What can you do? Use your words as weapons for moral change. Use the privileged air you breathe to speak out against slavery to everyone you know and everyone you meet. We need you. We need more of our white brothers and sisters to break their silence. We need you to speak out in the street in the counting house in the prayer meeting in the conference room by the fireside from the pulpit, but especially at the polls. Convince your father to vote. It is a crime that he has the right, but never has gone to the polls – not once.

SUSAN Quakers have no interest in voting. The government is corrupt. If he votes, he becomes a part of that corruption. The government wages war. If he votes, he condones that violence.

FREDERICK But if he votes –

SUSAN He has no interest in voting. Neither do I.

FREDERICK You ask me what you can do. I say use your words. You say we need more than words. I say convince your father to vote. You say he will not vote. Why did you ask for my opinion if you did not want to hear it? I hate to tell you, Susan, but white folks have a problem with listening. And the only thing harder for you to do than to listen to a black man is to hear him. A shipwrecked man was cast upon the sands of a faraway beach.

SUSAN What?

FREDERICK Days before, when the sailors had set sail, the sea was smooth with a smiling surface. Only after they were well embarked, did the waves turn to fury and send the ship to destruction and doom. The one man who lived, upon waking on the sands of this faraway beach, cursed the sea for deceiving him. For destroying his ship. For drowning everyone but him. Much to the shipwrecked man’s surprise, the sea arose and replied: “Lay not the blame on me, O sailor, but on the winds. By nature, I am as calm and safe as the land itself, but the winds fall upon me with their gusts and gales, and lash me into a fury that is not natural to me.”

SUSAN Am I the shipwrecked man? Or are you? Is my father?

FREDERICK I am partial to Aesop and his Fables. Not only because Aesop was born a slave, or that he was African, or that he gained his freedom with his own cunning and intellect, but because Aesop forces us to think about our own twisting, changing, selfish nature.

SUSAN What is the wind?

FREDERICK What is the wind?

SUSAN Will you please try the peach cobbler?

FREDERICK Fine, yes – I will try it.

[FREDERICK picks up the dish of cobbler. The fork falls from the plate to the ground]

SUSAN I will get you another fork.

FREDERICK No need. My hands will do just fine. Wait. Have you had any?

SUSAN No. But I am starting to think you never will, Mr. Douglass.

FREDERICK Stop calling me Mr. Douglass. We are nearly the same age.

SUSAN What shall I call you then?

FREDERICK Call me what your mother and father call me.

SUSAN You are a great and famous man – I cannot call you Fred.

FREDERICK I am your parent’s friend. I am your brothers’ and sisters’ friend. I am yours as well.

SUSAN Even though I put you off?

FREDERICK It is the trait I most desire in my friends.

SUSAN Frederick. Fred. No. Frederick.

FREDERICK Have some cobbler.

SUSAN I will later.

FREDERICK I insist. Ooo. This is the best cobbler I have ever tasted.

SUSAN My mother said that is what you told her about her cobbler.

FREDERICK I did. But I had not yet had yours.

[They laugh.]

SUSAN . . . Do you believe this can ever be a country for all?

FREDERICK I hope it can be, but Susan. . . there are great many people who will do anything in their power to prevent that from happening.

SUSAN I know.

FREDERICK You do not know. And I hope you will never know the depths of hatred that I have seen man descend to.

SUSAN Then let us – us women and men – reach for the heights together.

[There is a brilliant, burst of light. The moment stops. It burns into their memory. After several moments, we hear the sounds of an angry mob]

Association Hall Anti-Slavery Society Meeting Albany, New York February 5, 1861

[It is ten-and-a-half years later. Evening. Smoke is everywhere. There is the pulsing sound of feet stomping, fists pounding walls, and a mob shouting: “Damn the abolitionists! Damn the abolitionists! Damn the abolitionists!” SUSAN, now 40 years old, and FREDERICK, now 42 years old, rush through a wooden door. They slam it shut behind them and lock it. They are in a small storage room. The smoke surrounds them. They cough. They cover their mouths with handkerchiefs]

SUSAN What happened?

FREDERICK Someone threw pepper in the stove. [The sound of the mob on the other side of the door grows louder.] Your lip is bleeding!

ASHLEY C. FORD End of Episode One.

This was The Agitators by Mat Smart, from the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission, the National Park Service, and PRX Productions.

The podcast adaptation was envisioned by Commission Executive Director Anna Laymon, with support from Kelsey Millay. Performances by Madeleine Lambert as Susan B. Anthony and Cedric Mays as Frederick Douglass. Directed by Logan Vaughn. Original music and score by Juliette Jones and Rootstock Republic. The production team includes Executive Producer Jocelyn Gonzales and Managing Producer Genevieve Sponsler. Post-production sound and mixing by Sandra Lopez-Monsalve and Ian Coss. Original music and score recorded, mixed, and mastered by Joshua Valleau. Theme song production by Hunter LaMar. Original music and score recorded, mixed, and mastered by Joshua Valleau. Vocals and Theme song production by Hunter LaMar. Additional production by Brett ‘Whitenoise’ White. Overture sound design by David Lamont Wilson. Additional music by Epidemic Sound. Special thanks to David Herman of Good Studio, Dan Dietrich of Wall-to-Wall Recording, and Erin Sparks and Jacob Mann at Edge Media Studios.

To learn more about the history of the suffrage and abolition movements, visit the show’s website at GO DOT N-P-S DOT GOV SLASH suffrage podcast.

Listener Companion from the National Park Service

Find out more about the people, places, and stories from Episode One.-

The Necessity of Other Social Movements

The Necessity of Other Social MovementsLearn about the key role of other social movements to the US struggle for woman suffrage.

-

The Language of Slavery

The Language of SlaveryLearn the difference between the language that centers the slaveholders vs. that which centers those held in bondage.

-

A Community Reading"What to the Slave is the 4th of July?"

A Community Reading"What to the Slave is the 4th of July?"Read and hear Frederick Douglass' speech, "What to the Slave is the 4th of July?" and learn more about its importance and impact.

Credits

This was The Agitators by Mat Smart, from the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission, the National Park Service, and PRX Productions.The podcast adaptation was envisioned by Commission Executive Director Anna Laymon, with support from Kelsey Millay.

Performances by Madeleine Lambert as Susan B. Anthony and Cedric Mays as Frederick Douglass.

Directed by Logan Vaughn. Original music and score by Juliette Jones and Rootstock Republic. The production team includes Executive Producer Jocelyn Gonzales and Managing Producer Genevieve Sponsler. Post-production sound and mixing by Sandra Lopez-Monsalve and Ian Coss.

Original music and score recorded, mixed, and mastered by Joshua Valleau. Theme song production by Hunter LaMar. Original music and score recorded, mixed, and mastered by Joshua Valleau. Vocals and Theme song production by Hunter LaMar. Additional production by Brett ‘Whitenoise’ White. Overture sound design by David Lamont Wilson. Additional music by Epidemic Sound. Special thanks to David Herman of Good Studio, Dan Dietrich of Wall-to-Wall Recording, and Erin Sparks and Jacob Mann at Edge Media Studios.

Last updated: November 25, 2020