by Dr. Joe Watkins, Tribal Liaison; Chief, Tribal Relations & American Cultures; and Supervisory Cultural Anthropologist

National Park Service, United States

February 8, 2016

These pages should serve as an introduction to an increasingly important topic within natural and cultural resource management.

There are various terms used in describing knowledge held and used by communities -- traditional knowledge (TK) is a broader field that utilizes knowledge of people who have lived in an area, and interacted with a specific locale, over generations.

Indigenous knowledge (IK) is centered on the knowledge held by people prior to colonization or interruption by another more recent group of people in an area.

Local knowledge (LK) is similar to Indigenous knowledge, but it can be ascribed to the lived experience of people who have inhabited an area for a long time, even if they have replaced the "indigenous" groups.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), as Peter Usher defines it, "refers specifically to all types of knowledge about the environment derived from the experience and traditions of a particular group of people." (emphasis in original). Like Western science, it is based on the accumulation of observations. It entails a cumulative body of knowledge transmitted through generations, as well as beliefs about how people fit into ecosystems. It's holistic in outlook and adaptive by nature and has been gathered by generations of observers whose lives depend on it.

Initially, TEK discussions occurred within anthropological studies, as travelers to various Indigenous cultures around the world brought back descriptions of the ways local populations approached plant science, animal husbandry, agriculture, and so forth. However, over time, other researchers began mining that data for information. Now, each branch of science from A to Z –from anthropology to zoology –are involved in trying to understand the myriad ways that cultural groups take advantage of their specific knowledges of their specific situations.

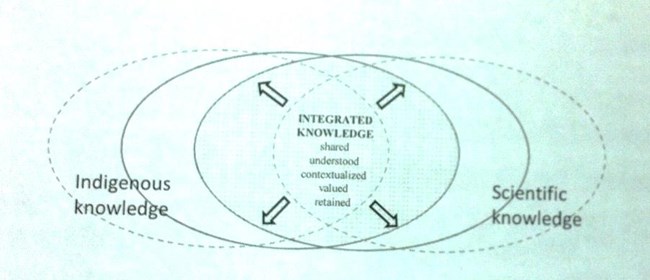

Much of the general knowledge can be found in texts related to ethnobotany, ethnopharmacology, cultural geography, ecological anthropology, or any of the many different subgroups of regularly funded academic research. However, it is important to recognize that TEK should not be considered to be in opposition to Western science.

This chart by Gratani and Butler (2010:117) is a good representation of the way that TEK and Western science each provide different ways of recognizing humans' relationships with nature, and the benefits that can be derived from integrating both perspectives.

Joe Watkins

The listing of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park as a World Heritage Property for its natural and cultural values represents years of work by the Anangu to assert their role as custodians of their traditional lands. This international recognition is a significant victory for the Anangu as it confirms the validity of tjukurpa, a religious philosophy that links Anangu to their environment, the Anangu culture as an integral part of the landscape, and Anangu understanding of and interaction with the landscape as being the primary tool for looking after their country.

It relates to the creation period when ancestral beings created the world, it provides rules for important behavior and living together, and it provides laws for caring with each other and the land that supports everyone. It tells of the relationships between people, plants, animals, and the physical features of the land. For more information on tjukurpa and its use at Uluru, visit https://parksaustralia.gov.au/uluru/pub/fs-tjukurpa.pdf.

The environment around Uluru represents the outcome of thousands of years of management under traditional practices governed by the Aboriginal people learned how to patch burn the country from lungkata, the blue tongued lizard. Now, although modern methods are used, the practice of lighting small fires close together during the cool season leaves burnt and unburnt areas in a pattern like a mosaic. This knowledge is now adopted as a major ecological management tool in the Park.

TEK exists everywhere, not only in faraway places like Australia. The National Park Service is committed to trying to integrate TEK with its natural and cultural resource management programs, and this website will help serve that purpose. Stay tuned!

Last updated: August 7, 2020