Photo by Joe Medley.

That old expression, "the early bird gets the worm," turns out to be truer than ever in urban settings today. In fact, recent studies are finding that some birds in noisy environments have taken to singing at night in order to be heard over the din of the city (Fuller et al. 2007).

Sound, just like the availability of nesting materials or food sources, plays an important role in ecosystems. Activities such as finding desirable habitat and mates, avoiding predators, protecting young, and establishing territories all depend on the acoustical environment. To continue these activities, animals are forced to adapt to increasing noise levels. For example, research shows that males of at least one frog species are adapting to traffic noise by calling at a higher pitch (Parris et al. 2009). This could be problematic for the females, because they prefer lower-pitched calls, which indicate larger and more experienced males. Human-caused noise has caused similar changes in multiple bird species, as well as squirrels, primates, bats, and cetaceans (Barber et al. 2009; Barber et al. 2010).

Photo by Ted Dunn

In general, a growing number of studies indicate that animals, like humans, are stressed by noisy environments (Shannon et al. 2015). The endangered Sonoran pronghorn avoids noisy areas frequented by military jets; female frogs exposed to traffic noise have more difficulty locating the male's signal; gleaning bats avoid hunting in areas with road noise (Barber et al. 2009). When these effects are combined with other stressors such as winter weather, disease, and food shortages, sound impacts can have important implications for the health and vitality of wildlife populations within a park (Ware et al. 2015).

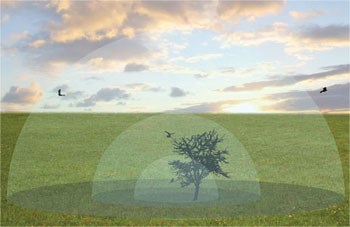

These findings are especially significant because national parks are under increasing noise pressure (Buxton et al. 2017). Noise levels in park transportation corridors today are many times the natural level (Mennitt et al. 2014). Air transportation can also affect life on the ground. Sound levels during peak periods in a high air traffic corridor in the Yellowstone backcountry, for example, were elevated by up to 5 decibels. The result is as much as a 70% reduction in the size of an area in which predators can hear their prey (Barber et al. 2009). Increasingly, careful consideration of the impacts of human-generated noise on wildlife is a critical component of management for healthy ecosystems in our parks.

Resources

To learn more about the body of scientific literature exploring the effects of noise on wildlife and humans, see the the Natural Sounds & Night Skies Division's Annual Synthesis of Studies on the Effects of Noise: a systematic, comprehensive up-to-date query of the scientific literature. To date, more than 800 peer-reviewed studies on the effects of noise on wildlife have been published. The synthesis summarizes the noise sources and effects, and highlights suggested readings from the most current research.

A selection of published research on the effects of noise on wildlife can also be found on the Additional Information page.

References

Barber, J. R., K. R. Crooks, and K. M. Fristrup. (2010). The costs of chronic noise exposure for terrestrial organisms. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 25(3): 180-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.002

Barber, J. R., K. M. Fristrup, C. L. Brown, A. R. Hardy, L. M. Angeloni, and K. R. Crooks. (2009.) Conserving the wild life therein--Protecting park fauna from anthropogenic noise. Park Science 26 (3). https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2201563

Buxton, R. T., M. F. McKenna, D. Mennitt, K. Fristrup, K. Crooks, L. Angeloni, and G. Wittemyer. (2017). Noise pollution is pervasive in U.S. protected areas. Science 356: 531533(2017). https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.aah4783

Fuller R. A, P. H. Warren, and K. J. Gaston. (2007.) Daytime noise predicts nocturnal singing in urban robins. Biology Letters, 3 (4): 368–370 https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2007.0134

Mennitt, D., K. Sherrill, and K. Fristrup. (2014). A geospatial model of ambient sound pressure levels in the contiguous United States. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 135 (5): 2746–2764. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4870481

Parris, K. M., Velik-Lord, M., & North, J. M. A. (2009). Frogs Call at a Higher Pitch in Traffic Noise. Ecology and Society, 14(1). http://www.jstor.org/stable/26268025

Shannon, G., M. F. McKenna, L. M. Angeloni, K. R. Crooks, K. M. Fristrup, E. Brown, K. A. Warner, M. D. Nelson, C. White, J. Briggs, S. McFarland, and G. Wittemyer. (2015). A synthesis of two decades of research documenting the effects of noise on wildlife. Biological Reviews 91(4): 982-1005. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12207

Ware, H. E., C.J.W. McClure, J.D. Carlisle, and J.R. Barber. (2015). A phantom road experiment reveals traffic noise is an invisible source of habitat degradation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (39): 12105-12109, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1504710112

Last updated: March 28, 2025