NPS Photo

Wapama (Steam Schooner)

Richmond, CA

Designated an NHL: April 20, 1984

Designation withdrawn: February 27, 2015

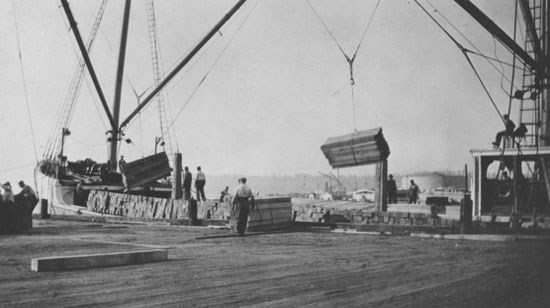

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 brought an influx of settlers and the spread of urbanization to the Pacific coast. The growth of new towns depended upon a ready supply of lumber for construction. As these towns arose, and as additional construction took place in established urban centers, more and more lumber was required. At first, lumber was imported from distant ports on the eastern U.S. seaboard and in the South Pacific. Logging in redwood groves near San Francisco Bay also met some of the demand, but by 1850 it was apparent that much more timber was required to meet the construction needs of several decades to come. The development of logging camps and mills in large stands of virgin Douglas fir and redwood on the rugged California and Oregon coasts solved the need for additional lumber. Since no direct route to the redwoods existed on land, and rail and wagon roads were difficult to build, the sea became the major highway of the Pacific coast lumber trade and commerce.

Using the sea for transportation, however, was also challenging. Pacific coastal fogs, strong winds, rocks, and powerful currents plagued mariners, and most shipping ports were mere "dog-holes" or slight indentations on the shore where a ship could barely fit, anchored close to shore and imminent destruction, and forced to load with wire chutes, cables, or lighters. These conditions quickly gave rise to a fleet of small sailing schooners built to maneuver in these difficult locations.

NPS Photo

Launched in 1915, the wooden-hulled Wapama was the last survivor of the approximately 235 steam schooners that served the Pacific Coast lumber trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These vessels formed the backbone of maritime trade and coastal commerce ferrying lumber, general cargo, and passengers.

Built with Douglas fir, Wapama departed from current shipbuilding practices. The ship was not reinforced with diagonal straps of iron to strengthen the hull, but was instead solidly built of wood with approximately three times the number of timber fastenings that an iron-reinforced vessel would have. The uniqueness of Wapama’s construction illustrates the human factor in ship design. Instead of following the standard design approved by the American Bureau of Shipping, the shipwrights who built the Wapama relied on their years of experience and intuition about what would work to construct the vessel. It is perhaps due to the shipwrights' skill with marrying old and new shipbuilding traditions that the Wapama survived her contemporaries.

Wapama's masts and spars supported booms for loading and off-loading cargo. The powerful winches were designed to allow Wapama to load and off-load by herself without the use of shore cranes. The ability to do this was an asset in the lumber trade where ports were primitive and lacked shore facilities for cargo loading.

NPS Photo

At the end of her active career, Wapama was displayed in the water at the San Francisco Maritime State Park, the National Maritime Museum of San Francisco, and, finally, as part of the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. By 1980, her wooden hull had become so badly deteriorated that she was removed from the water and placed on a barge. Ultimately, she was towed to a berth in Richmond, California.

After a series of condition assessments and stabilization measures, the National Park Service concluded in the 1997 General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement for the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park that, due to Wapama’s extremely poor condition, the dismantling of the ship should occur.

The dismantling process removed and encapsulated hazardous material, and removed the pilothouse and transferred it to a storage facility. The 30-ton engine was transported to Hyde Street Pier in San Francisco for display. Other significant elements, artifacts, and machinery were saved and will be used to help create a permanent interpretive exhibit at the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

The dismantling process was completed in August 2013. The Landmark designation was withdrawn on February 27, 2015, and the property was also removed from the National Register of Historic Places.

Last updated: August 29, 2018