NPS/Erin Borgman

Alpine Communities—Unique but Rapidly Changing

Loraine Yeatts, Adjunct Researcher, Denver Botanic Gardens

National parks feature some of the most dramatic, high mountain landscapes in the world. Visitors lured to sweeping mountaintop vistas may not realize how much life actually thrives right under their feet. On these windswept, sparsely vegetated slopes, alpine plants and animals stake their hardy claims. They are remarkably tough—adapted to high winds, hot and cold temperature extremes, thin soil, and very little moisture. But alpine communities are facing new challenges that threaten their ability to adapt. Rapid climate change is impacting the alpine zone. In addition, heavy visitor use, the invasion of exotic species, and air-borne pollutants like nitrogen and ammonium can disturb this community. In the face of these challenges, unique alpine species, like the American pika (Ochotona princeps) and the tiny Gray’s draba (Draba grayana), may struggle to persist.

These challenges are not unique to U.S. parks. Around the world, alpine ecosystems are changing rapidly in response to stressors, especially climate change. An international program called the Global Observation Research Initiative in Alpine Environments, or GLORIA, started tracking these changes in 2001. At high-elevation GLORIA sites around the world, observers collect vegetation and soil temperature data to track how conditions are changing. Understanding these changes is vital to land managers focused on protecting alpine biodiversity—the assemblage of species that call the alpine ecosystem home.

GLORIA Sites in U.S. National Parks

Several high-elevation national parks have established GLORIA monitoring sites, including two of the first GLORIA sites in North America.

Rocky Mountains

In the Rocky Mountains, Glacier National Park was the first to join the GLORIA network in 2003 and is coordinated by the US Geological Survey. It was also the first GLORIA site in North America! Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve and Rocky Mountain National Park followed in 2009. The NPS Climate Change Response Program (CCRP), established in 2010, sought to collaborate across agencies, universities, and other partners to enhance inventory and monitoring of climate-sensitive indicators in four vulnerable landscapes: high elevation, high latitude, coastal/marine, and arid lands. Targeting the high-elevation landscapes, three NPS Inventory and Monitoring Networks designed a way to expand monitoring: Enhanced Monitoring to Better Address Rapid Climate Change in High-Elevation Parks, A Multi-Network Strategy. This enhanced monitoring strategy identified alpine vegetation and soils as one of seven key resources. Consequently, a new GLORIA site in the Rocky Mountains was established in Yellowstone National Park. NPS also established and currently monitors a GLORIA site in the Pecos Wilderness in the southern Rocky Mountains of New Mexico, though it is not within a national park boundary.

Great Basin and Sierra Nevada

West of the Rocky Mountains, GLORIA monitoring occurs in Great Basin and Sierra Nevada national parks. The Dunderberg Peaks site on the border of Yosemite National Park share’s Glacier National Park’s claim to fame as one of the first GLORIA sites in North America. The three other sites are Mount Langley in the southern Sierra Nevada (Sequoia National Park), a site in Death Valley National Park, and a site in Great Basin National Park. A network of monitoring partners, GLORIA Great Basin, leads data collection at these sites in coordination with national park service staff and others.

View the following table and interactive map of GLORIA sites monitored in or nearby national parks:

| GLORIA Target Region | Date Established (resurveys are scheduled every 5 years) |

Coordinated By |

|---|---|---|

| US-GNP Glacier National Park (Montana) |

2003 | US Geological Survey |

| US-SND Sierra Nevada Dunderberg (on Yosemite National Park boundary, California) |

2004 | GLORIA Great Basin |

| US-GRB Great Basin National Park (Nevada) |

2008 | GLORIA Great Basin |

| US-RMN Rocky Mountain National Park, Rocky Mountains (Colorado) |

2009 | Rocky Mountain Network |

| US-GSD Great Sand Dunes National Park (Colorado) |

2009 | Rocky Mountain Network |

| US-LAN Mt Langley, southern Sierra Nevada (in Sequoia National Park, California) |

2010 | GLORIA Great Basin |

| US-YNP Yellowstone National Park (Wyoming) |

2011 | Greater Yellowstone Network |

| US-DEV Death Valley National Park (California) |

2013 | GLORIA Great Basin |

| US-PEK Pecos Wilderness (New Mexico) |

2016 | Rocky Mountain Network |

Measuring Alpine Zone Health—GLORIA Field Methods

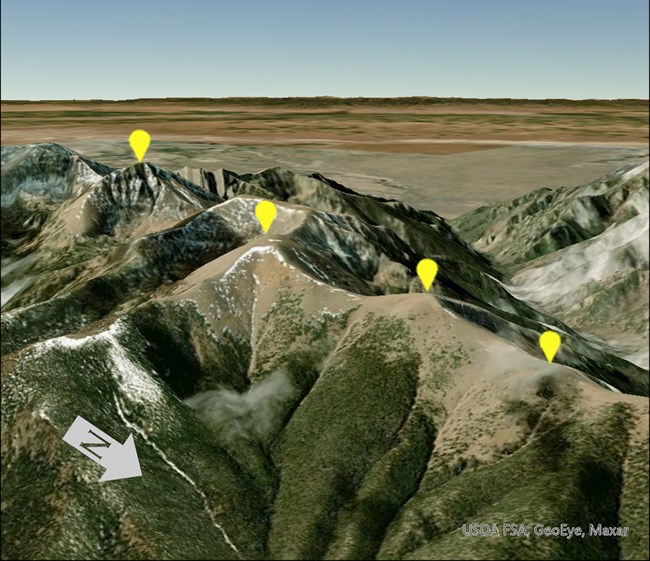

USDA FSA GeoEye Maxar

Establishing a new site and collecting data at the site follow methods on the GLORIA website and in the GLORIA Field Manual.

Establishing a Site

A GLORIA “site” is a Target Region containing sampling sites at four neighboring summits. The summits are usually grouped fairly closely together and differ primarily in elevation. Their proximity ensures similar underlying geology, climate, and history of disturbance so that the main difference is just elevation. This allows researchers to examine how alpine plants and animals at different elevations are responding to climate—and not other factors, like different soil types.

Collecting Data

At each summit, a cluster of four 1 m2 plots (a quadrat cluster) is established facing each of the four cardinal directions—north, south, east, and west. This totals 16 plots per summit. Every five years, the 16 plots on each summit are resampled to track vegetation and soil conditions.

www.gloria.ac.at

NPS/Funabashi

Plants

Observers record the different vascular plant species inside plots, as well as how much each species covers the ground, a measure known as vegetation cover. Following a strict survey protocol, this provides a quantitative measure of vegetation and how it may be changing inside the plots.

Outside the 1 m2 plots, observers record a qualitative measure of vegetation conditions. They do a careful visual census inside two different “summit sections” to note the variety and abundance of plant species in each section. The top section includes the area between the summit and 5 m down from it in elevation. The bottom section is the area between 5 and 10 m below the summit. This helps assess whether plant species are moving higher in elevation over time.

NPS

Soil

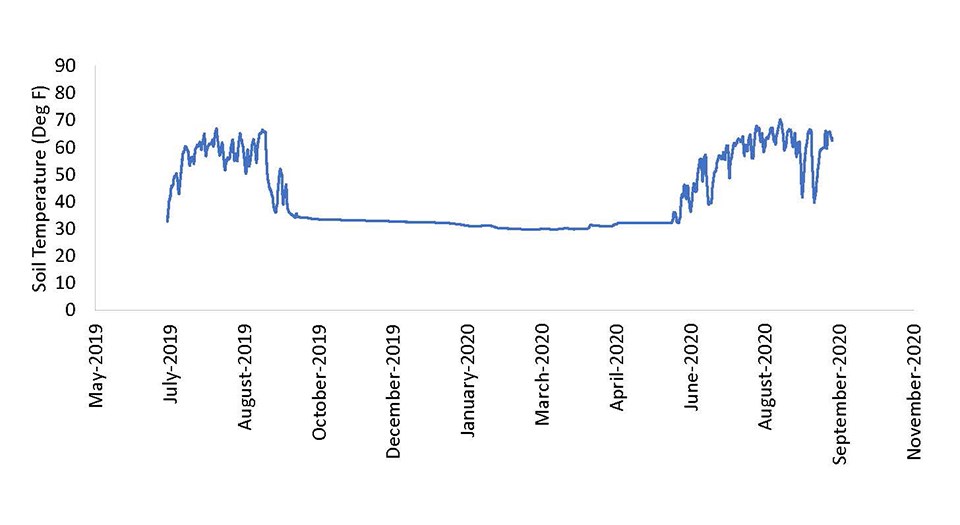

A datalogger buried 10 cm deep into the soil records soil temperature every hour, which is closely tied to air temperature. Soil covered in snow stays at a constant temperature, but as the snow melts away and exposes the ground, soil temperature begins to fluctuate. Therefore, tracking the temperature of the soil as it warms after the winter tells a lot about air temperature, snow cover, and the timing of snowmelt.

NPS

Ground Cover

Within both the 1 m2 plots and the two summit sections, observers also record the relative cover of different surface types. Surface type categories include

- vascular plants

- solid rock

- scree

- lichens

- bryophytes (mosses and liverworts)

- bare ground

- litter (dead plant material)

Monitoring ground cover helps track how vegetative cover may be changing over time. For example, are previously vegetated plots converting to rock?

NPS

Photo Documentation

During each visit to a target region, observers take a complete set of photographs to document vegetation and soil conditions within each 1 m2 plot and at the larger summit section scales. These photographs offer a valuable visual comparison of plots over time.

Additional Measurements in National Parks

Plant species, plant cover, ground cover, and soil temperature are collected at all GLORIA sites around the world. However, more types of information can be gathered if desired. Some national parks follow enhanced monitoring protocols that collect additional information, depending on park needs. Examples of additional measures include bryophyte species (mosses and liverworts) detected, trampling and grazing impacts, and soil texture and chemistry. Periodically, additional research also occurs at these GLORIA sites.

Assessing Alpine Health

Because changes in alpine environments occur relatively slowly, sites are sampled every five years. Since establishment, many of the GLORIA monitoring sites in national parks have been sampled two or three times. With each new resurvey, the growing dataset sheds more light on how alpine plants and animals are responding to changes in climate and other stressors.

Fortunately, enough data have been collected from some GLORIA sites in national parks to begin analysis. NPS scientists with the Rocky Mountain Network, Greater Yellowstone Network, and national parks and partners will study GLORIA data from parks in the Rocky Mountains as part of a Focused Condition Assessment funded by the NPS Water Resources Division. The study will help to answer several important questions:

-

How do soil temperature and moisture impact vegetation by influencing water availability?

-

Which plant species appear to be the key, most resilient species for restoring alpine areas?

-

Which species are particularly vulnerable and need protection where possible?

-

Does the mix of species (community composition) in a site modify the effects of climate?

- What kinds of changes are occurring in the amount of bare ground, or the mix of species present, that could affect habitat quality?

- Are plant species shifting into new ecological niches? (Shifting where they live or how they use their habitat.)

- Should we add new GLORIA locations or collect new types of information to better understand vulnerable species or habitat types?

In the bigger picture, GLORIA data may provide insight to better understand the risks and vulnerabilities for species that rely on alpine vegetation, like the American pika or key pollinators. This information will inform park managers about the changes occurring and improve their ability to make decisions that will help conserve these environments.

Colorado State University

Learn More

To learn more about GLORIA monitoring, visit the following websites:

NPS Rocky Mountain Inventory and Monitoring Network alpine monitoring

NPS Greater Yellowstone Inventory and Monitoring Network alpine monitoring

Contacts:

Last updated: September 10, 2024