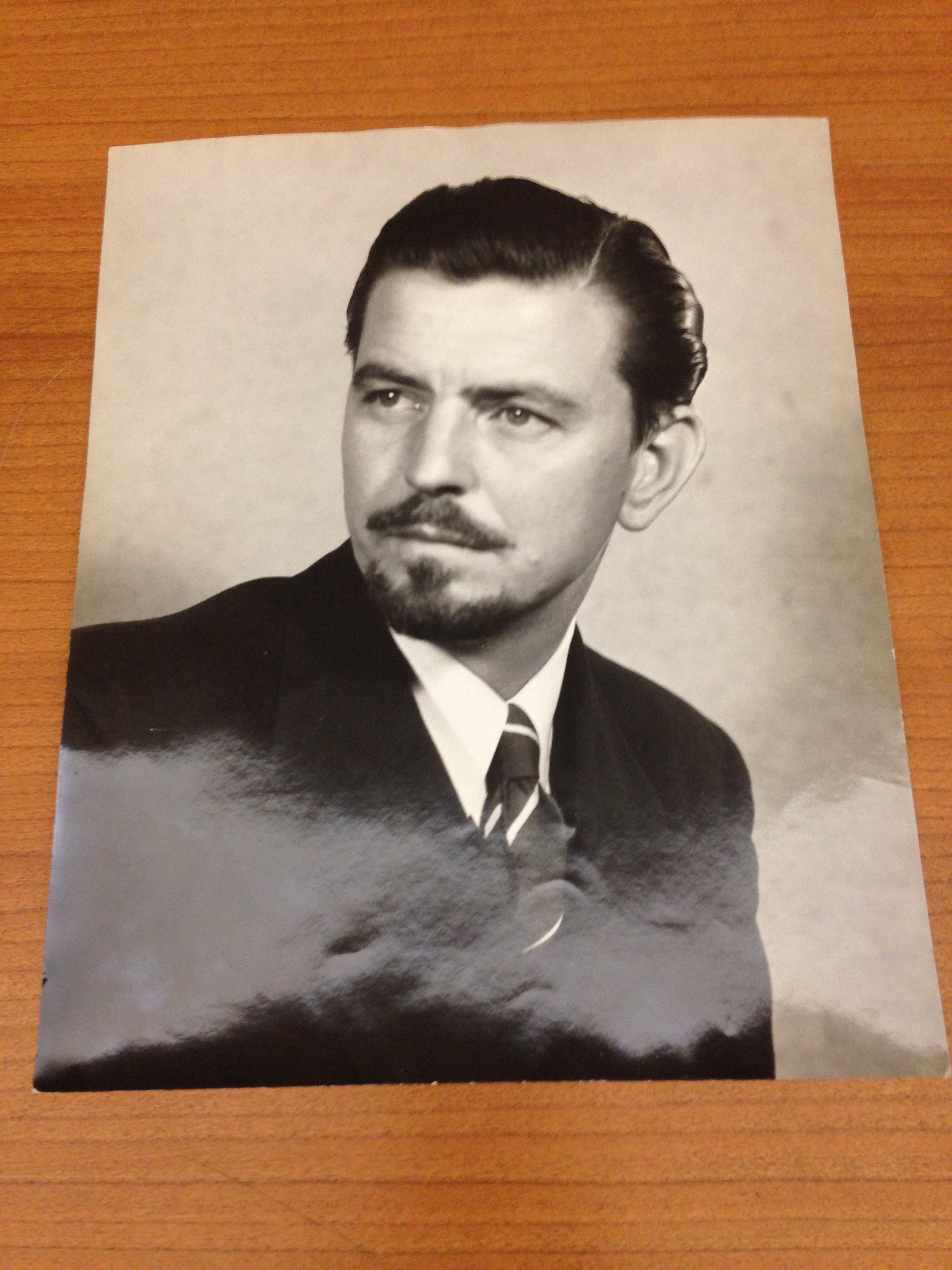

Caption: Black and white photo of Joseph Danysh in the 1930s pictured with dark hair and moustache, a dark suit and tie. (San Francisco Public Libraries, www.sfpl.org/sfphotos)

Danysh was hired at the very beginning of the FAP. His responsibilities grew to include 11 western states. His job was to build a broad base of community support and participation for state and local arts programs for which he seemed naturally adapted. His knowledge of the art and local artists led him to hire many of them either directly or indirectly for the FAP, including Hilaire Hiler and Richard Ayer who worked on the bathhouse project at 900 Beach Street. Danysh credited the New York Museum of Modern Art as an early influence in his interest in contemporary art. He sought the company of artists in San Francisco who were experimental, exploratory and edgy. Their work was unusual and little understood, but tame in comparison with today’s art. At the time, he found museums did not exhibit the work of young artists in San Francisco unlike New York Museum of Modern Art whose sole purpose was to exhibit modern art. In 1929, the opening exhibition included Cezanne, Gauguin, Seurat, and van Gogh. MOMA selected the four Post-Impressionists from an extensive list of pre-eminent painters of the 19th century for their pioneering work of a new genre of art; Post-Impressionism arising from the Impressionists era, as well as their mastery of former traditions.

In April of this year, San Francisco Maritime NHP celebrated the Maritime Museum’s 80th anniversary by opening the third floor to the public and honoring Fine Arts Conservator Anne Rosenthal’s work of reconstructing some of the missing parts of the murals while minimizing impacts to the historic fabric of the work. The materials she used was to be removable without damaging the original work in keeping with the unwritten art conservation’s law of reversibility. Rosenthal describes the result of her work as, “looks old, but well cared for” with the modern modifications to the room apparent with close inspection. Visitors to the Maritime Museum may contrast Richard Ayer’s “Nautical Abstraction” bas relief murals on the third floor with some of the elements of Post-Impressionism such as small brush strokes, an open composition, an accurate sense of natural light as an effect of time, and ordinary subjects in motion. Though the colors in Ayer’s murals are muted and derived from the colors of the outside—old brick from the Ghirardelli building and the gray of the pavement of Polk Street on the south wall, ocean blues and greens of the bay on the north wall— Ayer’s lines are not fuzzy and dreamlike like Post-Impressionism, but stark, geometric, and definitive.

Caption: Photo of Richard Ayer’s abstract compass rose decoration in black, coral, brown, gray, and blue terrazzo on the third floor of the Maritime Museum formerly known as the Aquatic Park Bathhouse. On a column shown above the compass rose, a dark ship trailing its wake are shown in grays, blue and off-white, while the passage of time is ascribed in geometric lines suggesting the wakes of ships that have passed earlier in time. [Photo credit: NPS Ranger Lou Salas Sian.]

Rosenthal completed the work, leaving the appearance of the room cohesive and unified. In Ayer’s work as reconstructed by Rosenthal, the openness of composition is retained; no two elements are connected, but spatially dispersed. Taken together on a palette of colors derived from the outside, there is a sense of motion in the careening sea birds, sharks swimming in formation, the portholes of a passing ocean liner reflecting sailboats on the bay, and the wakes of ships. Ayer’s motifs go every which way like the scene of a busy bay as seen from the wrap around windows of the third floor. Even the standing rig on the west wall appears to loom head-on with the observer. Somehow, perhaps in his use of color, Ayer seems to pull the elements of the floors, walls and ceiling together in one elegant banquet hall set off by weighty chrome chandeliers and glass.

Caption: The recently reconstructed 1930s banquet hall of the Aquatic Park Bathhouse, now known as the Maritime Museum. Heavy chrome, ship wheel chandeliers hang from the ceiling. Walls are painted in shades and hues of blues, grays, rust, and greens. The column on the left is decorated with signal flares, and the prow of a ship. For the columns and walls, Richard Ayer designed nautical motifs such as cowl vents, plimsoll, tugboats , and seabirds. The floor is decorated with a highly stylized representation of the sounding charts of the Bay. [Photo credit: NPS Ranger Lou Salas Sian.]

In a 1964 interview for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Richard Ayer (age 55) tried to explain his design. “It’s very hard to describe,” Ayer said, “There are six or eight large columns that support the ceiling or roof, everything. And great windows overlooking the Bay. On these columns I decorated all the sides with marine motifs and anchor chains, sails and all kinds of various symbols, radio signals, signal flags, all that; anything that would pertain to that. It was all very modern. I mean, there were no cute little sailboats running around in there; there was enough of that on the Bay that you could see.”

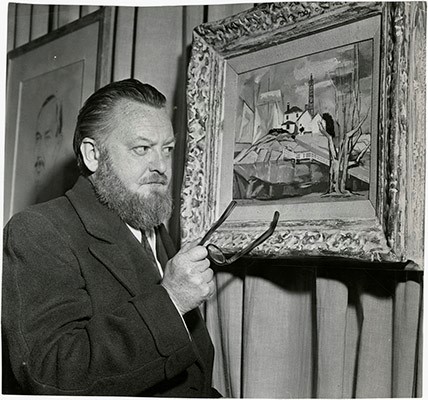

Caption: Black and white photo of an older Richard Ayer with a beard, holding his eyeglasses and looking at a framed painting on display. (San Francisco Public Library, http://sflib1.sfpl.org:82/record=b1046254).

A few years later, Ayer visited the Maritime Museum, and found his work was covered by layers of paint, carpet, and plywood. He did recall that William Mooser, the project’s supervisor and the driving force behind the ocean liner-shaped Maritime Museum, hated him, but later they got along. Ayer also decorated the building’s Blue Room on the east end of the second floor, to which Hilaire Hiler, the project’s art director and a contributing painter, had added yacht club pennants “for kicks”. “Why, it looks like a kindergarten, he’d say,” said Ayer of Mooser, “He would make those kind of little cracks anyway.”

Caption: Sepia-tone photograph of Hilaire Hiler holding an artist’s brush and palette, standing and applying paint to his design of the merman on one of the large canvasses that make up the murals in the lobby of the Maritime Museum. [Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library].

Hiler was a man whom Danysh greatly admired and like many of Hiler’s team, they always had a lot of fun working together. Under Hiler’s design direction, a small group of artists and crafts people decorated the Maritime Museum Building. During this time and through friendly chats, Ayer, who was mostly self-taught, acquired and applied some of Hiler’s color theory. In the Prismatarium room, on the west end of the second floor, Hiler painted his Psychological Color Wheel on the circular ceiling. He was most proud of this work, which was left untouched and openly displayed through the early years of the Maritime Museum. Hiler went on to teach his color theory at well-respected art schools.

When Hiler and Ayer were brought on board in 1934, the bathhouse building was just two bull-dozed holes in the ground, according to Ayer. Though the building was not yet built, Hiler insisted the decorations should complement the function of the building; that is, a public bathhouse with showers and concessions for the people who swam in the bay. Unlike many of the FAP art in federal buildings found throughout the country, the art in the bathhouse was mostly apolitical, whimsical and aquatic, an “undersea arabesque,” as Hiler described the murals he painted for the lobby.

If you would like to see the recently reconstructed murals by Hilaire Hiler, Richard Ayer, the sculptures of Sargent Johnson and Beniamino Bufano and works by many other artists supported by the Federal Arts Project, come by the Maritime Museum at 900 Beach Street for a chat with rangers and docents at one of the open houses held on the third Saturday of each month, 1 PM – 3 PM. After all, the artists intended the Aquatic Park building to be a Palace for the Public, a gift from them to you. For more information about the Maritime Museum Open House, contact Park Ranger Lou Salas Sian, lou_sian@nps.gov.