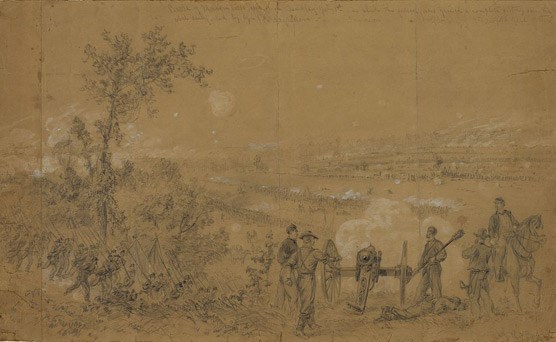

The Seven Days battles ended with a tremendous roar at Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862. The contending armies collided for the final time that week on ground that gave an immense advantage to the defenders—in this case McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. With the security of the James River and the powerful United States Navy at his back, McClellan elected to stop and invite battle. The Confederates, elated by their victories but frustrated by their inability to achieve truly decisive battlefield results, obliged McClellan by attacking Malvern Hill. The hill itself was a modest elevation about 2 ½ miles north of the James River. Its strength lay not in its height, but rather in its fields of fire. Gently sloping open fields lay in front of the Union position, forcing any Confederate attacks against the hill to travel across that barren ground. McClellan unlimbered as much artillery as he could at the crest of the hill, facing in three directions. Nearly 70,000 infantry lay in support, most of them crowded in reserve on the back side of the hill. General Lee recognized the power of Malvern Hill. In tandem with James Longstreet, one of his top subordinates, Lee devised a plan where Confederate artillery would attempt to seize control of Malvern Hill by suppressing the Union cannon there. Lee believed his infantry could assault and carry the position if they did not have to contend with the fearsome Union batteries.

Library of Congress The Confederate bombardment failed, but Lee’s infantry attacked anyway, thrown into the charge after a series of misunderstandings and bungled orders. Lee himself was absent when the heaviest fighting erupted. He was away looking for any alternate route that would allow him to bypass Malvern Hill. But once the attack started, Lee threw his men into the fray. Some twenty separate brigades of Southern infantry advanced across the open ground at different times. As the Confederate leaders had feared, the Federal batteries proved dominant. Most attacks sputtered and stalled well short of the hill’s crest. Occasionally McClellan’s infantry, commanded by Fitz John Porter, George Morell, and Darius Couch, sallied forward to deliver a fatal volley or two. Pieces of Confederate divisions led by D. H. Hill, Benjamin Huger, D. R. Jones, Lafayette McLaws, Richard S. Ewell, and W. H. C. Whiting advanced at different times, always without success. General John B. Magruder organized most of the attacks. Late in the day, a few Union brigades and some fresh artillery raced to the hilltop in support. But in fact only a small segment of the Army of the Potomac saw action at Malvern Hill. The dominance of the position enabled less than one-third of the Union army to defeat a larger chunk of the Confederate army at Malvern Hill. As with each of the other battles during the dramatic week, darkness concluded the action. Malvern Hill had demonstrated the power and efficiency of the Union artillery in particular. Confederate leaders and soldiers alike could look back on poor command and control as the principal cause of their defeat. The casualty totals were more balanced than expected for a battle in which the outcome never was in doubt. Slightly more than 5000 Confederates fell killed and wounded, while roughly 3000 Union soldiers met a similar fate. Today Malvern Hill is the best preserved Civil War battlefield in central or southern Virginia. Nearly unaltered in appearance since 1862, the battlefield's rural setting and extensive walking trails offer an ideal environment for visitors to study the climactic battle of the Seven Days Campaign. |

Last updated: February 26, 2015