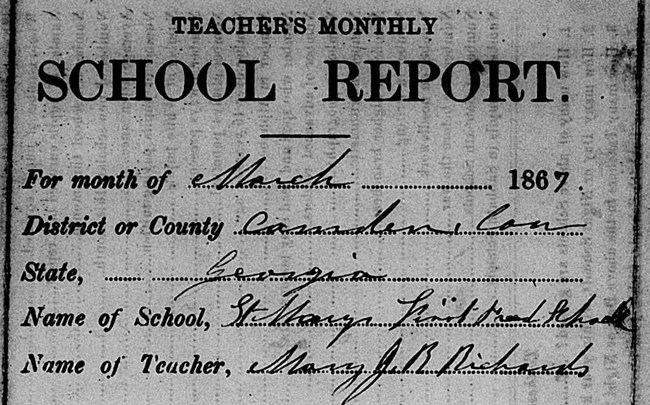

A Black Union Spy in RichmondIn 1911, fifty years after the start of the Civil War, Annie Van Lew Hall was interviewed for a story in Harper’s Magazine. She told the publication that as a child, she had known an African American woman named “Mary Elizabeth Bowser” who was a spy during the war, working in the home of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and secretly gathering information there.1 The story became the stuff of Civil War legend as it was repeated and embellished over the next century. The basis of Hall’s story was true: her aunt, Elizabeth Van Lew, did operate an espionage ring in the Confederate capital, and an African American woman named Mary was a part of it. The other details of Hall’s story, though, are mostly incorrect. Evidence unearthed by historians who went in search of “Mary Elizabeth Bowser” indicated that the woman Annie Van Lew Hall remembered those fifty years later was actually named Mary Jane Richards, and prompted the discovery of a true story much more detailed and remarkable than the fragmentary Harper’s article of 1911.2Mary Jane Richards was most likely born in Virginia around 1840. No official record of her birth exists, and the identity of her parents is unknown. To a Richmond court in 1860, she said her mother was a slave belonging to Eliza Van Lew.3 In public speeches in New York in 1865, she told two audiences that she did not know who her parents were.4 In a private conversation with a Reverend Crammond Kennedy and Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1867, Richards stated that her mother was white, and her father was “a mixture of the Cuban-Spaniard and negro.”5 The first probable appearance of Mary Jane Richards in the historic record is the accounting of a baptism on May 17, 1846, of “Mary Jane,” identified by the recorder at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond as “a colored child belonging to Mrs. [Eliza] Van Lew.”6 The Van Lew family sent Mary Jane Richards to school in Princeton, New Jersey, in the 1850s,7 and Richards appears in the records of the American Colonization Society among a group of Black Virginians bound for Liberia in 1855.8 Richards wrote back to the Van Lew family of her dissatisfaction with conditions there, and the Van Lews paid her passage to return to Virginia in 1860.9 On March 5, 1860, Mary Jane Richards arrived by ship in Baltimore, and from there she traveled to Richmond, Virginia.10 Virginia law on the eve of the Civil War forbade African Americans from entering the state. By returning to Virginia, Richards was breaking the law.11 In August of 1860, Mary Jane Richards was arrested in Richmond for "perambulating the streets claiming to be a free woman of color."12 When apprehended, she gave a false name, telling her jailers that her name was Mary Jane Henley. While in captivity, she amended her claim and said her name was Mary Jones. Finally, she was released to the custody of Eliza Van Lew, having admitted her name was Mary J. Richards.13 If she was a free African American, Richards’ presence in Richmond was illegal and she could have, under Virginia law, been sold into slavery for the crime of having entered the state. Instead, Eliza Van Lew told the court that Richards was enslaved. If Richards was enslaved by the Van Lews, she could legally be released into their custody. Richards left jail and Van Lew paid a ten dollar fine for “permitting her slave, Mary Jane, to go at large.”14 (Richards appears at various times and places in historical records under at least seven different names, including Mary Jane Richards, Mary Jane Henley, Mary Jones, Richmonia Richards, Richmonia R. St. Pierre, Mary J.R. Garvin, and Mary J. Denman) On April 16, 1861, St. John’s Church recorded the marriage of Wilson Bowser and someone named Mary. The record indicates that the groom and the bride were both “servants to Mrs. E. L. Van Lew.”15 This was most likely Mary Jane Richards, and this marriage is probably the source of the name “Mary Bowser” that Annie Van Lew – about six years old at the time – would recall to Harper’s Magazine fifty years later. At the same moment, the Civil War began and Richmond was quickly declared the capital of the new Confederacy. When war arrived, the Van Lew family first quietly commiserated with their friends and neighbors who supported the United States and abhorred the Confederacy, which had been founded for the avowed purpose of perpetuating human slavery. When nearby battles brought prisoners and casualties, the Van Lews and Mary Jane Richards offered care and comfort to United States Army prisoners in the city.16 By 1864, Elizabeth Van Lew had established contact with the U.S. government and was supplying military intelligence to army leaders and assisting in the escape of prisoners of war from Richmond. Free and enslaved African Americans, including Mary Jane Richards, were vital members of the espionage network that operated in Richmond in the latter part of the war.17 On February 9, 1863, a new identification as a free person of color was issued to “Mary Jane Henley” in Richmond. There is every reason to believe that this was Mary Jane Richards, because she had used this alias in 1861.18 In November, 1864, Wilson Bowser was advertised as a runaway slave, presumably having self-emancipated by fleeing wartime Richmond.19 Richards herself left Richmond by the end of 1864, as well.20 On April 3, 1865, United States army forces liberated Richmond, and Mary Jane Richards quickly returned. As a literate and educated Black woman, her skills were much in demand in the time immediately following the war, when Northern aid societies created schools to teach the formerly enslaved. Richards taught for various aid societies at “Ryland’s Church” (First African Baptist Church)21 and Ebenezer Baptist Church in the summer of 1865.22 By the end of the summer, she had become disillusioned with the work and the attitudes of the white Northern charitable organizations, and she left Richmond.23 In September of 1865, Mary Jane Richards gave two public speeches at churches in Harlem and Brooklyn. In both instances, she used a pseudonym, calling herself first “Richmonia Richards,” and then “Richmonia R. St Pierre,” and thrilled New York audiences with her narrative of being a spy in the Confederate capital and her strong opinions about politics and current events. (You can read the full text of the newspaper stories recounting her speeches here: RICHMONIA RICHARDS in the NEW YORK ANGLO-AFRICAN, October 7, 1865 RICHMONIA R. ST. PIERRE in the BROOKLYN DAILY EAGLE, September 25, 1865) In her remarks recorded in the Anglo African, Richards comes closest to the imagined narrative of "Mary Elizabeth Bowser" in the Harper's story of 1911 by claiming to have entered - one time - the home of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. The Anglo African's reporter recorded Richards saying "she went into President Davis’s house while he was absent, seeking for washing, and while there was conducted into a private office by one of the clerks, when she opened the drawers of a cabinet and scrutinized the papers. While thus employed Jeff. came in and inquired of her what she was doing there, but considering she was colored allowed her to go in peace."24 By 1867, Richards appears in the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau, operating a school in St. Marys, Georgia. Also in 1867, she met the Reverend Crammond Kennedy and Harriet Beecher Stowe, speaking to them privately about her wartime service.25 In June of 1867, Richards informed the Freedmen’s Bureau that she had married a man named Garvin and would be closing her school and moving to the West Indies.26 She did not, however, leave the country, and in August of that same year, she signed her monthly school report “Mrs. John L. Denman.” The last known record of Mary Jane Richards is a letter, written from Greenwich Village in New York City in October, 1870 and sent to Elizabeth Van Lew in Richmond. In it, Mary (signing as “M.J. Denman”), indicates her desire not to return to Richmond, to grow beyond the influence of the Van Lew family and to succeed on her own in New York. Working as a seamstress and planning to return to school to be a teacher, Mary Jane Richards Denman said what was likely a final goodbye to Richmond, and, for now, disappeared from the historical record.27 There was no “Mary Elizabeth Bowser” who worked at the home of Jefferson Davis, as Annie Van Lew Hall misremembered in 1911. There was, however, a remarkable woman named Mary Jane Richards who defied the established order by being an educated, world-traveling African American woman in the 1850s, who worked to destroy American slavery by taking immense risks to be a secret fighter in the Civil War, and who contributed to the education of scores of Black Americans who had been denied that opportunity for generations, even as she navigated the uncertainties of Reconstruction-era American society herself. 1 William Gilmore Beymer, Miss Van Lew (Harper's Monthly Magazine, 1911), 86-99. 2 Elizabeth Varon, in Southern Lady, Yankee Spy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003) first correctly identified Mary Jane Richards as an African American member of the Van Lew household, participant in the Civil War espionage network, and the real person who inspired the later "Mary Elizabeth Bowser" legend. Modern scholarship on the topic has continued with Lois Leveen's extensive research and interpretation of the Mary Bowser legend and Mary Richards's factual biographical details. See, for example, The Spy Photo that Fooled NPR, the U.S. Army Intelligence Center, and Me (The Atlantic, June 27, 2013) The Vanishing Black Woman Spy Reappears (Los Angeles Review of Books, June 19, 2019) She Was Born Into Slavery, Was a Spy, and Is Celebrated As a Hero - But We're Missing the Point of the 'Mary Bowser' Story (TIME, June 19, 2019) 3 Richmond Whig, August 21, 30, 1860. 4 "Addresses by a Colored Lady and Henry Ward Beecher." Brookyln Daily Eagle, 25 September 1865, p.1 and "Richmonia Richards." (New York) Anglo African, 7 October 1865, p.1 (Anglo African accessed via Geisel Library at the University of California at San Diego) 5 "Letter from Rev. Crammond Kennedy." The American Freedman 2 (April 1867), 205. 6 Rev. L.W. Burton, Annals of Henrico Parish (1904), 332. 7 Reverend Crammond Kennedy reported that Richards told him she was educated in Princeton, New Jersey, and in an 1870 letter, Richards (now identifying as M. J. Denman), stated that she was living in New York with schoolmates from Princeton. 8 Robert T. Brown, Immigrants to Liberia, 1843-1865: An Alphabetical Listing (Philadelphia: Institute for Liberian Studies, 1980), 50, cited in Varon, Southern Lady, Yankee Spy, 29. 9 Elizabeth Van Lew to Anthony D. Williams, September 10, 12, 1859, American Colonization Society Papers, Library of Congress, cited in Varon, Southern Lady, Yankee Spy, 29-30. 10 "Return of the Stevens," African Repository (April 1860), 116, cited in Varon, Southern Lady, Yankee Spy, 30. 11 The Code of Virginia (Richmond: Ritchie, Dunnavant & Co., 1860), 809-810. 12 Richmond Whig, August 21, 30, 1860. 13 Ibid. 14 Richmond Daily Dispatch, September 11, 1860, 1. 15 Rev. L.W. Burton, Annals of Henrico Parish (1904), 248. 16 "Addresses by a Colored Lady and Henry Ward Beecher." Brookyln Daily Eagle, 25 September 1865, p.1 17 Elizabeth Van Lew, in her diary, noted in 1864: "When I open my eyes in the morning, I say to the servant, 'What news, Mary?' and my caterer never fails! Most generally our reliable news is gathered from negroes, and they certainly show wisdom, discretion, and prudence, which is wonderful." (Van Lew, "Personal Narrative," May 6, 1864, 660-661.) 18 Varon, Southern Lady, Yankee Spy, 31. Varon cites Hustings Court Minutes, Hustings Court Minute Book no. 28, [1862-1863], 302, Library of Virginia, for the issuance of the Mary Jane Henley identification. 19 Richmond Daily Dispatch, November 29, 1864, 1. 20 "Richmonia Richards." (New York) Anglo African, 7 October 1865, p.1. 21 "Letter from Rev. Crammond Kennedy." The American Freedman 2 (April 1867), 205. 22 The Freedmen's Record, v.1 April 1865, 119. 23 "Addresses by a Colored Lady and Henry Ward Beecher." Brookyln Daily Eagle, 25 September 1865, p.1 24 "Richmonia Richards." (New York) Anglo African, 7 October 1865, p.1. 25 "Letter from Rev. Crammond Kennedy." The American Freedman 2 (April 1867), 205. 26 Richards to Eberhardt (of the Freedmen's Bureau), April 7, 1867, Registered Letters Received, Georgia Superintendent of Education, vol.1, 1865-1867, Education Records, Bureau of Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, cited in Varon, Southern Lady, Yankee Spy, 212. 27 M.J. Denman to Elizabeth Van Lew, 31 October, 1870, Library of Virginia, Elizabeth Van Lew Papers, 1842-1911. Series I: Letters and Papers.

Courtesy of The Valentine. |

Last updated: May 4, 2025