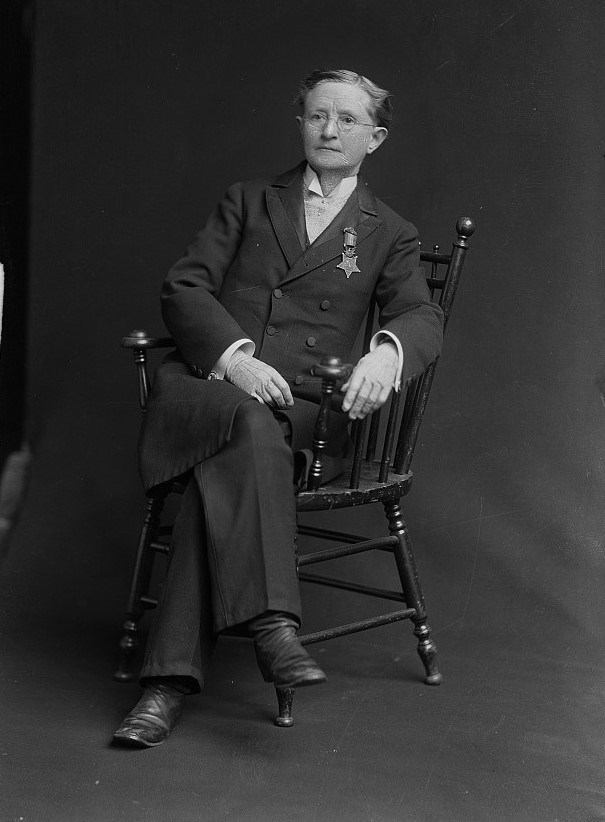

C.M. Bell, photographer. Walker, Dr. Mary. [Between 1873 and 1916] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Mary Walker was born on November 26, 1832 and raised in Oswego, NY. Her parents, Alvah and Vesta Walker, instilled progressive values in their children at a young age – they split domestic chores equally, sheltered freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad, and encouraged their five daughters to pursue professional educations and careers. To this end, Mary attended Syracuse Medical College, graduating in 1855 to become one of only a handful of female doctors in America. Dr. Walker struggled to be taken seriously by potential patients, who were reluctant to accept that a woman could be a competent doctor. She was also regarded as an oddity for rejecting Victorian-era dress codes. She believed corsets and long, heavy skirts were bad for women’s health, instead preferring a style which she called Reform Dress; it included a pair of loose-fitting pants covered by a simple, knee-length skirt. Dr. Walker faced ridicule for her clothing choices throughout her life and was often harassed or arrested for nonconformity. After the Battle of Bull Run in 1861, Dr. Walker traveled to Washington, hoping that the Union’s urgent need for surgeons would outweigh their unwillingness to legitimize a woman doctor. Despite her optimism, she was denied a commission. Instead, she worked as a volunteer surgeon, first in a makeshift soldiers’ hospital in the US Patent Office, then at field hospitals in Warrenton, Fredericksburg, and Chattanooga. In early 1864, Dr. Walker was granted an unofficial contract as an Acting Assistant Surgeon for the 52nd Ohio Volunteers (Army of the Cumberland) and joined them in Tennessee. In addition to treating wounded soldiers, she often crossed into Confederate-held territory to provide medical assistance to injured, sick, and starving civilians, and, perhaps, to gather intelligence for the Union. On April 10, 1864, Dr. Walker had an unlucky encounter with a Confederate sentry in enemy territory – she was captured and sent to Castle Thunder military prison in Richmond, VA.

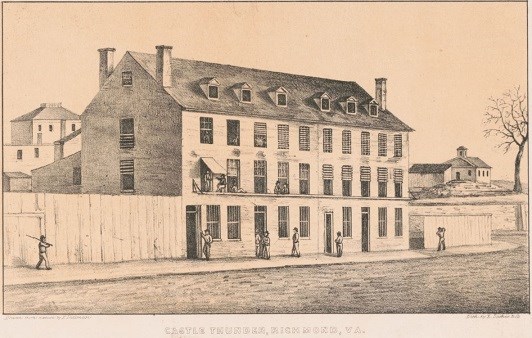

"Castle Thunder, Richmond, Va" from Library of Congress. Castle Thunder was created from a former tobacco warehouse and two adjacent buildings on Cary Street. It became increasingly overcrowded as the war continued, and when Dr. Walker arrived in 1864 it likely held between 700 and 1000 prisoners – mostly Confederate deserters, captured Union civilians, political prisoners, and African Americans. The notoriously harsh prison guards had recently been investigated by the Confederate House of Representatives for excessive brutality and accidental shootings of prisoners. Dr. Walker described filthy cells infested with bed bugs, lice, and rats, and meager rations riddled with mold. She became very ill during her time in Castle Thunder, suffering bronchitis, severe weight loss, and permanent damage to her eyesight. On August 12, 1864, Dr. Walker was freed in a prisoner exchange, traded for a Confederate Major, which she considered an affirmation of her worth to the United States. She spent the next six months in the Union’s Louisville Female Military Prison serving as an Acting Assistant Surgeon, a role which she found difficult – male coworkers continually undermined her authority by encouraging prisoners to refuse treatment and medication from her. Dr. Walker also may have struggled with her mental health after having spent nearly five months in Castle Thunder as a prisoner herself. In April 1865, she wrote to Post Medical Director Dr. Edward Phelps requesting to be transferred out of the prison. Shortly after, the end of the war signaled the end of Dr. Walker’s tenure as an Army Surgeon. In the ensuing year, Dr. Walker contacted numerous authorities to request a pension for her service and compensation for having damaged her vision at Castle Thunder, which prevented her from a full return to medical practice. After countless denials, she and her friends appealed directly to President Johnson. Though he agreed that Dr. Walker had rendered valuable services to the United States, he argued that she could not be granted a pension since she had never been an officially commissioned officer in the Army. Instead, he awarded Dr. Walker with the Medal of Honor on January 25, 1866, making her the first and only woman to receive this accolade. Dr. Walker devoted herself to many causes after the war: securing pensions for wartime nurses, advocating for universal suffrage, promoting dress reform, and keeping up with medical advancements. She published two books and spent many years traveling internationally, giving speeches about her experiences in the war and the causes she was passionate about. She passed away on February 21, 1919, firmly believing it was only a matter of time before her then-radical ideas became commonly accepted. |

Last updated: March 30, 2022