Last updated: July 22, 2022

Place

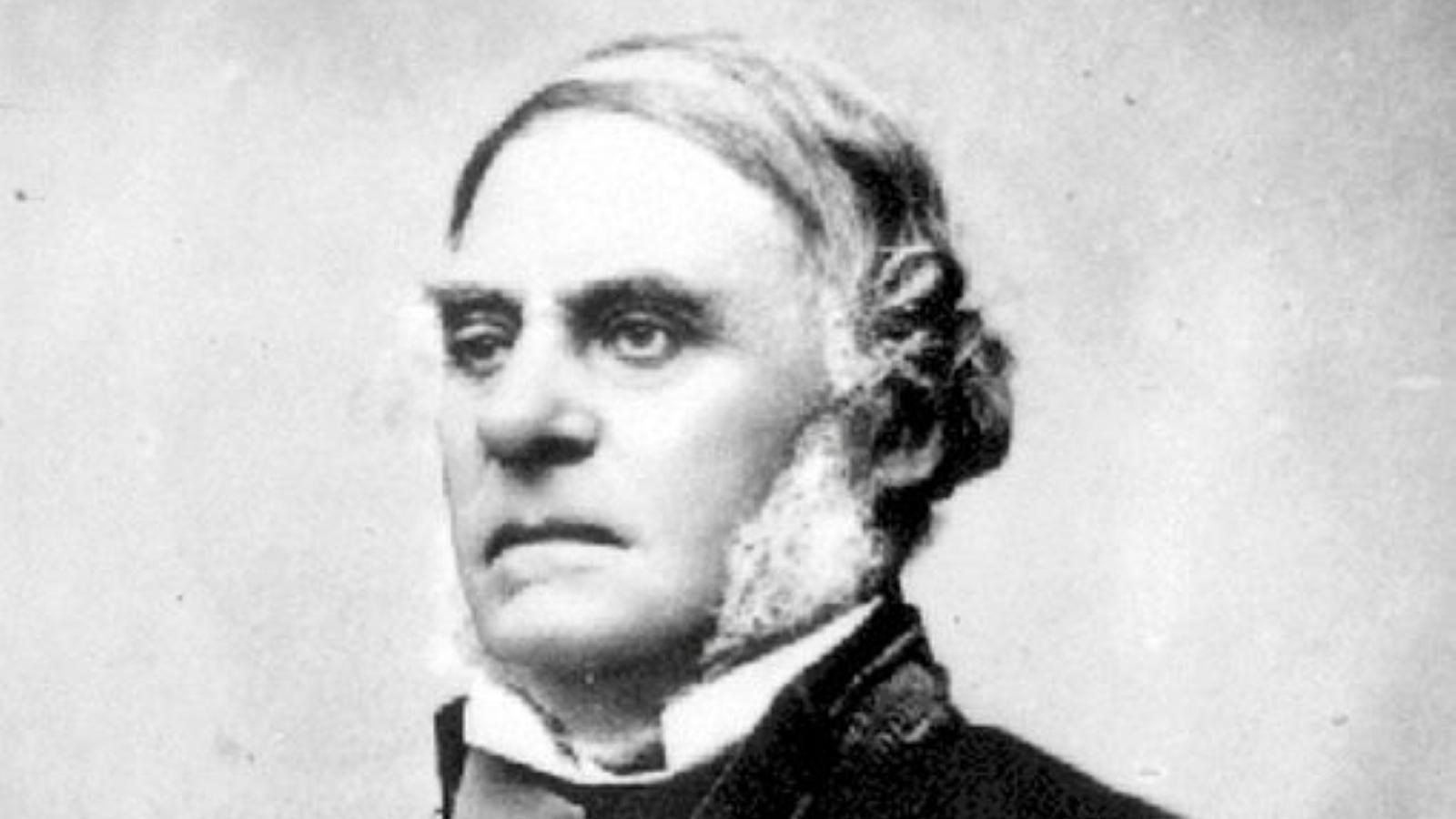

James Douglas Statue

Quick Facts

Location:

Victoria, British Columbia

Amenities

1 listed

Benches/Seating

This statue commemorates James Douglas who was the royal governor of Vancouver Island and British Columbia and Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, making him the most powerful British official in the Pacific Northwest at the time of the Pig War. Douglas also had the most experience in the region, having served as an agent of British Empire in the Pacific Northwest for 39 years by the time Lyman Cutlar shot his company’s pig. Unlike his colleagues in the Royal Navy, who advocated for a peaceful solution to the Pig War Crisis, Douglas encouraged swift and decisive action to confront the American occupation of San Juan Island.

James Douglas was born in 1803 to Martha-Ann Ritchie, a free Barbadian of Afro-Scottish descent and a well-connected Scottish merchant who met in the South American colony of Guyana. Described in official documents as a “Scotch West Indian,” Douglas’s multiracial heritage was no hindrance to his success in the Hudson’s Bay Company, which had many multiracial employees at all levels of the company during his tenure. Douglas’s own 1837 marriage to Amelia Connolly, whose father was a fur trade superior and whose mother was a member of the Cree Tribe of Native Americans, demonstrates the ubiquity of cross-cultural marriages in the North American fur trade. Later Douglas descendants, likely in an effort to avoid racial stigmatization, claimed that Douglas was born in Lanarkshire, Scotland where he was sent to school as a young man and omitted his diverse heritage from his history. Douglas is far from the only historic figure in the Pacific Northwest whose racial background has been falsely remembered by history to characterize the settler era Northwest as a less diverse place than it really was.

James Douglas began working in the fur trade in North America in 1819 when he was only fifteen years old and labored in this industry for his entire working life. Douglas’s career required him to balance the hyperlocal needs of the isolated and culturally diverse trading outposts where he lived with the financial and market forces that governed a commercial empire ruled from London. Douglas learned to balance diplomatic and trade relationships with indigenous people and defuse tension between white settlers and Native Americans who were both important clients of his employer. Though Douglas's duties as a clerk required rigorous and methodical recordkeeping, it could also involve brute force, such as the time Douglas and other young employees of the Northwest Company intimidated Hudson’s Bay Company by brandishing “Guns, Swords, Flags, Drums, [and] Fifes” at their rivals.

After the 1821, merger of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company, Douglas’s work also brought him all over North America. In his first decade on this continent, Douglas lived at a fort on Lake Superior, in Saskatchewan, at two locations in New Caledonia, and in Oregon. His work also required great strength and endurance; one of the many major voyages he took was about 6000 miles in length and required the use of boats, canoes, horses, and snowshoes with a group of around 30 employees. As Douglas was promoted to higher positions, he negotiated with Russian, Mexican, American, and indigenous leaders to extend his company’s footprint into new markets and attain labor and products.

James Douglas was based at the Hudson’s Bay Company post at Fort Vancouver, now Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, until 1849, when Britain surrendered control of the present-day state of Washington to the United States. Douglas relocated the Northwestern headquarters for the Hudson’s Bay Company to Victoria, which is visible from our park on clear days. In 1851, Douglas was appointed royal governor of Victoria, making him the most important political and business leader in the colony. In the 1850s, US settlers took over existing Hudson’s Bay Company posts managed by Douglas, such as Fort Nisqually. In 1858, massive numbers of Americans moved through Victoria and into the Fraser River Valley in the mainland, which Douglas also controlled. With more Americans in his colony than British settlers, Douglas feared displacement and only through keen use of Hudson’s Bay Company and Royal Navy assets was he able to control a situation in which Americans could have once more used force to seize British North American colonies and Hudson’s Bay Company assets.

Though it is impossible to know what role Douglas’s diverse heritage played in his actions during the Pig War era, it is likely significant. In 1858, just prior to the Pig War, Douglas sent a letter to San Francisco’s Black community, encouraging members to immigrate to Vancouver Island, which lead several hundred Black families to settle on the island at a time in which Douglas tried to limit white migrants from California. As a Hudson’s Bay Company official, Douglas employed numerous Hawaiian immigrants and had witnessed how racist laws in the Washington and Oregon Territories stripped them of their rights and property. Douglas was mindful of this recent history, as well as the conflict over slavery that would soon erupt into the Civil Warm as he fought for a tough line against the US soldiers that he regarded as having invaded his colony and his company’s property in the summer of 1859.

Douglas retired in 1864, after nearly 45 years of work in the fur trade. He was knighted by Queen Victoria for his services to the British Empire. Though he went to Europe on a grand tour after his retirement, Douglas lived the rest of his life in Victoria, the city that he had done more than any person to build. Today, Douglas is widely considered “the Father of British Columbia.”

James Douglas was born in 1803 to Martha-Ann Ritchie, a free Barbadian of Afro-Scottish descent and a well-connected Scottish merchant who met in the South American colony of Guyana. Described in official documents as a “Scotch West Indian,” Douglas’s multiracial heritage was no hindrance to his success in the Hudson’s Bay Company, which had many multiracial employees at all levels of the company during his tenure. Douglas’s own 1837 marriage to Amelia Connolly, whose father was a fur trade superior and whose mother was a member of the Cree Tribe of Native Americans, demonstrates the ubiquity of cross-cultural marriages in the North American fur trade. Later Douglas descendants, likely in an effort to avoid racial stigmatization, claimed that Douglas was born in Lanarkshire, Scotland where he was sent to school as a young man and omitted his diverse heritage from his history. Douglas is far from the only historic figure in the Pacific Northwest whose racial background has been falsely remembered by history to characterize the settler era Northwest as a less diverse place than it really was.

James Douglas began working in the fur trade in North America in 1819 when he was only fifteen years old and labored in this industry for his entire working life. Douglas’s career required him to balance the hyperlocal needs of the isolated and culturally diverse trading outposts where he lived with the financial and market forces that governed a commercial empire ruled from London. Douglas learned to balance diplomatic and trade relationships with indigenous people and defuse tension between white settlers and Native Americans who were both important clients of his employer. Though Douglas's duties as a clerk required rigorous and methodical recordkeeping, it could also involve brute force, such as the time Douglas and other young employees of the Northwest Company intimidated Hudson’s Bay Company by brandishing “Guns, Swords, Flags, Drums, [and] Fifes” at their rivals.

After the 1821, merger of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company, Douglas’s work also brought him all over North America. In his first decade on this continent, Douglas lived at a fort on Lake Superior, in Saskatchewan, at two locations in New Caledonia, and in Oregon. His work also required great strength and endurance; one of the many major voyages he took was about 6000 miles in length and required the use of boats, canoes, horses, and snowshoes with a group of around 30 employees. As Douglas was promoted to higher positions, he negotiated with Russian, Mexican, American, and indigenous leaders to extend his company’s footprint into new markets and attain labor and products.

James Douglas was based at the Hudson’s Bay Company post at Fort Vancouver, now Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, until 1849, when Britain surrendered control of the present-day state of Washington to the United States. Douglas relocated the Northwestern headquarters for the Hudson’s Bay Company to Victoria, which is visible from our park on clear days. In 1851, Douglas was appointed royal governor of Victoria, making him the most important political and business leader in the colony. In the 1850s, US settlers took over existing Hudson’s Bay Company posts managed by Douglas, such as Fort Nisqually. In 1858, massive numbers of Americans moved through Victoria and into the Fraser River Valley in the mainland, which Douglas also controlled. With more Americans in his colony than British settlers, Douglas feared displacement and only through keen use of Hudson’s Bay Company and Royal Navy assets was he able to control a situation in which Americans could have once more used force to seize British North American colonies and Hudson’s Bay Company assets.

Though it is impossible to know what role Douglas’s diverse heritage played in his actions during the Pig War era, it is likely significant. In 1858, just prior to the Pig War, Douglas sent a letter to San Francisco’s Black community, encouraging members to immigrate to Vancouver Island, which lead several hundred Black families to settle on the island at a time in which Douglas tried to limit white migrants from California. As a Hudson’s Bay Company official, Douglas employed numerous Hawaiian immigrants and had witnessed how racist laws in the Washington and Oregon Territories stripped them of their rights and property. Douglas was mindful of this recent history, as well as the conflict over slavery that would soon erupt into the Civil Warm as he fought for a tough line against the US soldiers that he regarded as having invaded his colony and his company’s property in the summer of 1859.

Douglas retired in 1864, after nearly 45 years of work in the fur trade. He was knighted by Queen Victoria for his services to the British Empire. Though he went to Europe on a grand tour after his retirement, Douglas lived the rest of his life in Victoria, the city that he had done more than any person to build. Today, Douglas is widely considered “the Father of British Columbia.”