Last updated: August 30, 2020

Place

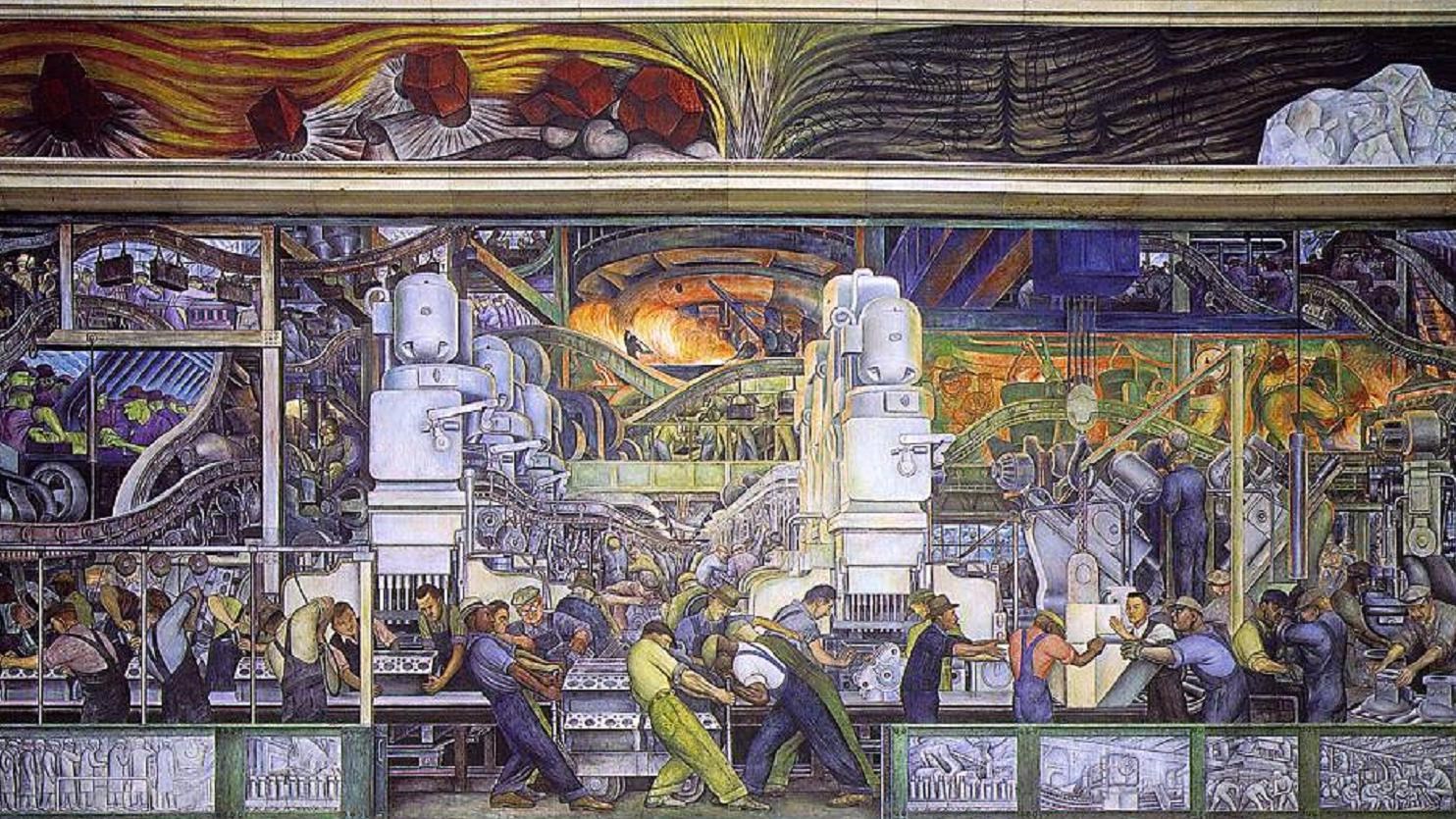

Detroit Industry Murals, Detroit Institute of Arts

Photo by Cactus.man, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=79406295

Between 1932 and 1933, artist Diego Rivera, a premier leader in the 1920s Mexican Mural Movement, executed one of the country's finest, modern monumental artworks devoted to industry. Often considered to be the most complex artworks devoted to American Industry, the Detroit Industry mural cycle depicts the city's manufacturing base and labor force on all four walls of the Detroit Institute of Arts Garden Court, since renamed the Diego Court. Rivera's technique for painting frescoes, his portrayal of American life on public buildings, and the 1920s Mexican Mural Movement itself directly led to and influenced the New Deal mural programs of the 1930s and 1940s.

The Mexican Mural Movement came into being in 1920s at the end of the Mexican Revolution. Mexico's new president wanted to promote a Mexican culture. He appointed a new Minister of Education, Jose Vasconcelos, who envisioned a comprehensive program of popular education to teach Mexican peasants what it meant to be Mexican. Vasconcelos' plan was to adorn public buildings with murals to promote a national identity. One of the more prominent painters of this program was Diego Rivera. Rivera studied at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts. He won a scholarship to study art in Europe, where he learned about Italy’s 13th and 14th century murals. This study helped him develop a philosophy of public art that would support the mural movement in post-revolutionary Mexico.

Rivera returned to Mexico in 1923, ready to create what would be some of his most significant art. Between 1923 and 1924, Rivera covered the walls of a three-story courtyard at the Ministry of Public Education Building with 124 frescoes. These made Rivera internationally famous and sparked the muralism movement. From those frescoes, the artform spread. Rivera's undisputed masterpiece marked a sudden turning point in the Mexican Art Movement.

Rivera's art was political and its messages intensified as the decade progressed. When he returned to Mexico, Rivera became involved with the Mexican communist movement, which began to show in his works. In 1926, Rivera's allegiance to the Mexican Communist Party led him to oppose American holdings and expansion in Mexico. This was evident in his 1928 caricature of American Industrialists in the Wall Street Banquet. This piece showed wealthy industrialists John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford, and their wives seated at a dinner table examining gold ticker-tape. In 1929, a new Mexican presidential administration outlawed the Communist Party. Rivera's fellow Communists wanted him to stop painting, as a form of protest, but he chose to continue painting. Because of this, he was kicked out of the Communist Party.

Rivera traveled to the United States in 1930 when he was invited to paint in San Francisco. In California, most of Rivera's murals were inspired by America's industrial society. His major works were the Allegory of California and Making of a Fresco. These depict the labor that goes into creating a city and a mural, and the people who carry out that work. His art in San Francisco differed from his work in Mexico, in that he reined in his political beliefs.

On May 26 1931, Rivera was commissioned to paint two large murals on the north and south walls of the Detroit Institute of Arts' Garden Court. The Institute's Arts Commission would pay $10,000 dollars from the Edsel B. Ford Fund, plus cover the cost of materials and plastering. The murals' content would be left to Rivera with approval from the Arts Commission. The project was expanded to cover all four walls of the Garden Court with the budget increasing to $20,899. The Ford Motor Company had a vested interest in Rivera's murals. The company wanted to improve its image after workers went on a hunger strike to improve working conditions.

Between April and July of 1932, Rivera toured and sketched Ford's River Rouge plant and other industrial sites. He made thousands of preliminary drawings. While Rivera was sketching, the walls were being prepared. In order to prepare the walls for a mural, wet plaster had to be applied and while it was wet, water-based tempera paint applied over it. The plaster was pre-mixed with pure lime, which serves as a binder. As the plaster dries, thin paint is permanently bonded to the surface through a chemical process. Rivera could then affix his finished drawings to the wall.

Rivera was painting in a city that was devastated by the Great Depression. Rather than portraying the Depression in his mural cycle, Rivera focused on the marvel of the modernistic and high-tech River Rouge complex and its impact on workers. He captures in the mural panels the technology of the Rouge, the brilliant condensation of the general flow of manufacture and transportation that governed the entire factory, and the tension on the determined faces of workers caused by performing the string of repetitive tasks at maximum speed.

Before the murals were unveiled, negative press began to emerge. A front-page Detroit News editorial called the murals un-American and foolishly vulgar. The paper stated that the work bore no relation to the soul of the community, to the room, to the building, or to the general purpose of Detroit's Institute of Arts. It also claimed that the murals were not a fair picture of the man who works short hours, must be quick in action, alert of mind, who works in a factory where there is plenty of movement. Some clergy were distraught over the vaccination panel.

In response and for publicity, the museum set up a press conference with clergy and the media. It broke in the Detroit papers, and within 10 days was all over the world. Supporters of the murals struck back against the negative media coverage. In a surge of enthusiasm for the murals, organizations and others circulated and signed petitions. Beyond the City of Detroit, the controversy extended to the national art community. Despite the controversy, the Arts Commission unanimously voted to accept the murals.

The Detroit Industry Murals consist of 27 panels spanning four walls. These panels depict industry and technology as the indigenous culture of Detroit. They emphasize a relationship between man and machine. Technology is portrayed in both its constructive and destructive uses, to illustrate the give-and-take relationships between North and South Americans, management and labor, and the cosmic and technological. The east and west walls depict the development of technology and the north and south walls show a representation of the four races, the automobile industry, and the secondary industries of Detroit-medicine, drugs, gas bomb production, and commercial chemicals.

The Murals' east walls begin the theme of Detroit Industry with the origins of human life, raw materials, and technology represented. In the center panel, an infant is cradled in the bulb of a plant whose roots extend into the soil, where, in the lower corners, two steel moldboard plowshares appear. Plowshares are used to plow under weeds and debris from the previous crop to replenish the soil with nutrients. They symbolize the first form of technology - agriculture - and relate in substance and form to the automotive technology represented on the north and south walls.

The theme of the technological development continues on the west wall, where the technologies of air, water, and energy are represented by the aviation industry, shipping and speedboats, and the interior of Power House #1. These images symbolize dualities in technology, nature and humanity, and in the relationship between labor and management. The wall shows both the constructive and destructive uses of aviation, the existence in nature of species who eat down the food chain as well as those who prey on their own kind, the interdependence of North and South America, and the interdependence of management and labor. This wall combines the religious symbolism of Christian theology with the ancient Indian belief in the coexistence and interdependence of life and death.

The north and south walls represent the four races, the automobile industry, and the other industries that are secondary to the automobile industry. These walls illustrate a theme similar to the east and west walls. They combine ancient and Christian symbols in their patterns with monumental figures on top, the workers' everyday world of the factories in the center, and small monochrome predella panels showing a day in the life of a worker on the lower edge.

The top of the north and south walls contains the "four races" panel. The four races of Diego's mural -- representing African, European, Asian, and American Indian identities -- take the position of the deity. The interiors of the factories represent the victim who is healed. The small monochrome panels of a day in the life of a worker take the place of the description of the event. Below the four races are panels representing geological strata showing iron ore under the red race, coal with fossils and diamonds under the black race, limestone under the white race, and sand and fossils under the yellow race.

The corner panels of the north and south walls contain Detroit's other industries: Vaccination, Manufacture of Poisonous Gas Bombs, Pharmaceutics, and Commercial Chemical Operations. These represent the themes of the unity of organic and inorganic life and the constructive and destructive uses of technology. The panels on the north and south walls show a common theme of depicting life being helped and harmed by technology. One panel shows a child being vaccinated while another panel shows life being threatened by poisonous gas bombs. All panels show some representation of life being sustained by the minerals represented in the geological strata.

The largest Detroit Industry Murals panel on the north wall focuses on the construction of the engine and the transmission of an automobile. The panel combines the interior of five buildings at the Rouge: the blast furnace, open hearth furnace, production foundry, motor assembly plant, and steel rolling mills. The panel represents all the important operations in the production of the automobile, specifically the engine and transmission housing of the 1932 Ford V-8. The panel shows the process of the how the engine is produced.

Visitors to the Detroit Institute of Arts can walk through the Diego Court and see these remarkable, historic murals in person. The museum offers a multimedia tour of the murals, available in Spanish and English, and guided tours of the museum.

Discover more history and culture by visiting the Detroit travel itinerary.