Last updated: March 17, 2021

Person

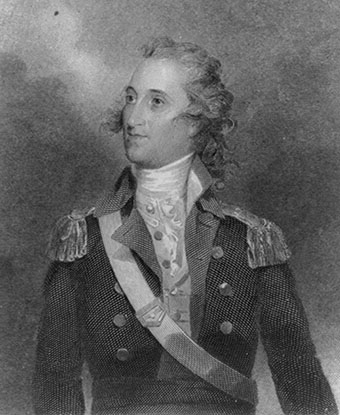

Thomas Pinckney

Library of Congress

Thomas Pinckney was born into a wealthy, influential family in Charleston, South Carolina on October 23, 1750. His father, Charles Pinckney, and mother, Elizabeth "Eliza" Lucas, sailed with their two sons, Thomas and his older brother, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, to England in 1753 in pursuit of educational opportunities. His parents sailed back to South Carolina in 1758 while Thomas and his brother stayed behind in England. Thomas Pinckney received a liberal education at Westminster School and Christ College, Oxford, and later studied law at the Middle Temple in the Inns of Court. He also briefly studied military science at the Royal Military Academy in Caen, France. His return to Charleston in December 1774 coincided with rising tensions between the colonists and the mother country. Despite his long stay in England, Pinckney and his family members supported the Patriot cause.

At the outbreak of war in 1775, Pinckney became a captain in the First South Carolina Regiment and was later promoted to major. He traveled to North Carolina and Virginia on recruiting missions and to supervise the construction of fortifications. The bulk of his early military service featured garrison duty in Charleston harbor. Pinckney even wrote his sister Harriott that she need not worry "for you may depend upon their being no fighting wherever I am." This prediction would prove incorrect when the British turned their attention to the American South, beginning in 1778. When the British invaded South Carolina in May 1779, from their base in Savannah, Georgia, they burned Pinckney's plantation on the Ashepoo River. During a lull in the fighting, he married Elizabeth Motte on July 22, 1779. Their marriage produced six children. In the fall of 1779, Pinckney served as a liason between Franco-American forces at the failed siege of Savannah.

When the British laid siege to Charleston in 1780, Pinckney urged the defense of the city, a strategy that proved disastrous for the Southern Department of the Continental Army when Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln surrendered the city to the British on May 12, 1780. Fortunately for Thomas Pinckney, he was not among the over 5,000 prisoners of war as Lincoln had sent him into the interior to search for expected reinforcements. He linked up with the remaining Continental Army soldiers in the Carolinas and became Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates's aide-de-camp. The hero of Saratoga, Gates had been sent south to revive the Patriot cause after the fall of Charleston. At the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780, Pinckney's leg was shattered by a musket ball, and he was captured, ending his active service during the American Revolution. The British defeated the Continental Army and southern militia at Camden, leading to the downfall of Gates as a military commander. In the years following the battle and even the end of the Revolution, Pinckney publicly defended Gates's strategic and tacticial decisions, blaming the poorly disciplined militia for the defeat at Camden.

After the war, Pinckney turned away from the law and focused on managing his plantations and his political career. He represented the city parishes of St. Philip's and St. Michael's in the state House of Representatives from 1776 until 1791. He was elected governor of South Carolina in 1787 and served one two-year term. He submitted the new federal Constitution to the state legislature and presided over the ratification convention in Charleston in 1788. In 1792, Pinckney accepted his most prestigious and challenging assignment yet: US minister to Great Britain.

As minister to Great Britain, Pinckney tackled difficult and unresolved issues from the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution and guaranteed American independence. Despite his efforts, Pinckney was unable to secure compensation for enslaved people who left the country during British evacuations. Similarly, he was unable to resolved disputes over British fortifications in the old Northwest and American fishing rights off Newfoundland. When Britain and France went to war in 1793, President George Washington feared for American neutrality. Washington sent John Jay in 1794 on a special mission to Britain. Temporarily superseded by Jay, Pinckney supported the mission and approved the controversial new treaty that Jay negotiated.

In November 1794, Pinckney was appointed envoy extraordinary to Spain. In Spain, Pinckney found great success as a diplomat and arguably achieved his highest point in a long public career. From June to October 1795, Pinckney worked to settle territorial and commerical disputes between the United States and Spain. The chief American goal at the time was to secure navigation rights along and at the mouth of the Mississippi River. The Treaty of San Lorenzo, signed on October 27, 1795, granted Americans the privilege to use the port of New Orleans and established a clear boundary between the United States and West Florida. This treaty helped pave the way for American settlement of the Southeast and for future territorial acquisitions in the region.

In 1796, Pinckney resigned his post and returned to South Carolina. Before his arrival, Federalists nominated him as their candidate for vice president. Because of political maneuvering, Pinckney finished behind Thomas Jefferson in the voting. In November 1797, Pinckney was elected to the US House of Representatives to complete William Smith's unexpired term. In Congress, he generally supported the administration of President Adams. He did, however, oppose the Sedition Act. He left Congress in 1801, and, except for another term in the South Carolina legislature from 1802 to 1804, withdrew from public life.

His retirement ended during the War of 1812 when he was commissioned a major general and given command of the Southern Division of the US Army. He worked to strengthen coastal fortifications and held overall command during the war with the Creeks, but he saw no action. After the war, Pinckney retired to his plantation on the Santee River, which he named El Dorado. In his retirement, he remained committed to agricultural innovations, which included using dikes to reclaim saltwater marshes for rice cultivation. In 1825, he became president general of the national Society of the Cincinnati. On November 2, 1828, Pinckney died in Charleston.