Last updated: July 7, 2024

Person

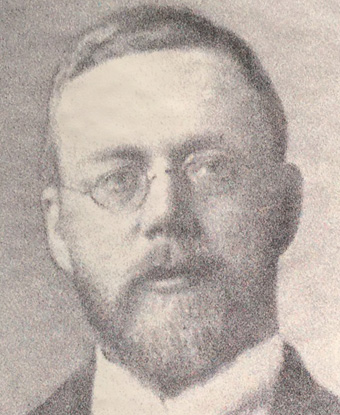

Reginald Fessenden

A pioneering inventor and known as the “Father of Voice Radio,” Reginald Fessenden is most well known for his work involving radio and sonar.

Born October 6, 1866, in Canada, Fessenden was the oldest of four children. His father was a Reverend in the Anglican Church of Canada, which caused the family to move around Ontario. Fessenden studied at Trinity College School in Ontario and at Bishop’s College (where he also taught) in Quebec. Before finishing his degree, Fessenden left to take the position of principal of the Whitney Institute in Bermuda. While there, he met his future wife Helen Trott, and developed a keen interest in science.

In 1886, Fessenden moved to New York in hopes of working for Thomas Edison. By the end of the year, he was hired as a tester at Edison Machine Works. Fessenden quickly began receiving promotions and was soon working directly for Edison in the laboratory as a junior technician and later becoming chief chemist. In 1890, Fessenden married Helen Trott and was laid off by Edison due to financial trouble. He bounced between different electrical companies until 1892, when he began pursuing a career as a professor. During this period, Fessenden welcomed his son in 1893.

In 1900, Fessenden left teaching and went to work for the U.S. Weather Bureau to help adapt radiotelegraphy to weather forecasting. Fessenden quickly began to make advances as he worked toward the development of audio reception of signals. On December 23, 1900, Reginald Fessenden sent the first transmission of voice over radio between two towers a mile apart located on Cobb Island in Maryland. While the message was difficult to understand, it proved that voice could be transmitted over radio.

In 1901, Fessenden moved to Roanoke Island to continue his experiments. He erected three 50-foot-tall radio towers at Weir Point on Roanoke Island, Cape Hatteras, and Cape Henry to conduct his research. In March of 1902, Fessenden successfully sent a 127-word message from Cape Hatteras to Roanoke Island. While what the message included was unknown, it was a major step for wireless voice transmission. However, disagreements with the U.S. Weather Bureau over the patents and discoveries led to Fessenden leaving his contract in August of 1902.

In November of the same year, he started working with two businessmen from Pittsburgh to finance selling wireless telegraph communication to those who would benefit from it (such as the U.S. Navy). The company was to be called the National Electric Signaling Company (NESCO). The goal was to determine how to transmit wirelessly across the Atlantic Ocean. A station was built at Brant Rock, Massachusetts and another built about 3,000 miles away at Machrihanish, Scotland. In January of 1906, Fessenden established transatlantic communication between Brant Rock and Machrihanish. The connection was unreliable and variable, but it had been done. However, before further testing could be completed the station in Machrihanish was destroyed in a storm. Fessenden refused to allow the setback to slow him down and decided to showcase the systems abilities.

On December 24, 1906, Fessenden began his broadcast that was heard as far away as Norfolk, Virginia. The broadcast included verses from the Gospel According to Luke, an Edison phonograph playing a recording of Handel’s “Largo” aria, a violin rendition of “O Holy Night” played by Fessenden and ended by wishing listeners a Merry Christmas. A similar broadcast was sent out on New Year’s Eve. The advancements made by Fessenden were not financially successful to the company, and in 1911 he was fired by NESCO. He sued NESCO for breach of contract and the case was not settled until 1928.

Fessenden ended his work with radio after he left NESCO but worked on other projects in other fields.His most extensive projects were based in marine communication. Fessenden worked with the Submarine Signal Company and invented the Fessenden oscillator. Unlike other forms of submarine signals (such as bells), the Fessenden oscillator was two-way, meaning it could both send out signals and receive them. This invention was a very early basis for sonar, echo sounding, and radar. The oscillator was soon put to use helping submarines signal each other and locating icebergs. At the beginning of World War I, Fessenden went to London to assist the Canadian government. He developed a device to detect enemy artillery and another to locate enemy submarines. Fessenden also created a version of microfilm. He later received patents for things like tracer bullets, turbo electric drive for ships, paging and even a television apparatus.

In 1921, Fessenden was awarded the Institute of Radio Engineers Medal of Honor and the next year was awarded a John Scott Medal by Philadelphia's Board of Directors of City Trusts. The most notable award came in 1929 when he was awarded Scientific American's Safety at Sea Gold Medal in recognition of his inventions.

Reginald Fessenden died on July 22, 1932 in Bermuda.