Last updated: May 4, 2021

Person

Maud Malone

Bain News Service Collection, Library of Congress http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ggbain.16068/

Maud Malone was born in New York City to Annie Malone and Dr. Edward Malone, both of whom were Irish immigrants. Both her father and her uncle Father Sylvester Malone (a priest) were among the founders of the New York Anti-Poverty Society. Maud's social activism and awareness ran in the family.

Maud Malone brought two important innovations to the women's suffrage movement in the US: open air meetings and parades. But if you look for Maud in the history books, chances are you won’t find her.

Personally, Maud was described as quiet, even bashful, with a winning smile, but in public she could spar with the best of them. Part of a Brooklyn family that supported underdogs and unpopular causes, she had grown up going to political meetings with her family in Manhattan’s Cooper Union.[1] She described their home as “a hotbed of activity whenever elections or any other political events took place.”

Maud herself was especially interested in women’s suffrage. The Manhattan librarian was frustrated that, by 1905, only four states allowed women to vote, all in the west. New York state was nowhere near considering women’s suffrage. To restart the movement, more people needed to be engaged. But how? The people who showed up to suffrage meetings already agreed with their ideas.

Maud liked to take long walks in New York City. On these walks, she saw Salvation Army preachers gather large crowds in public. She also noticed Socialists gathering workers outside of factory yards. Maybe women could also speak publicly in parks and on sidewalks and convert men and women to their cause. Later on, she said, “I decided that if we wanted to vote we had to go to the people and ask for it.”

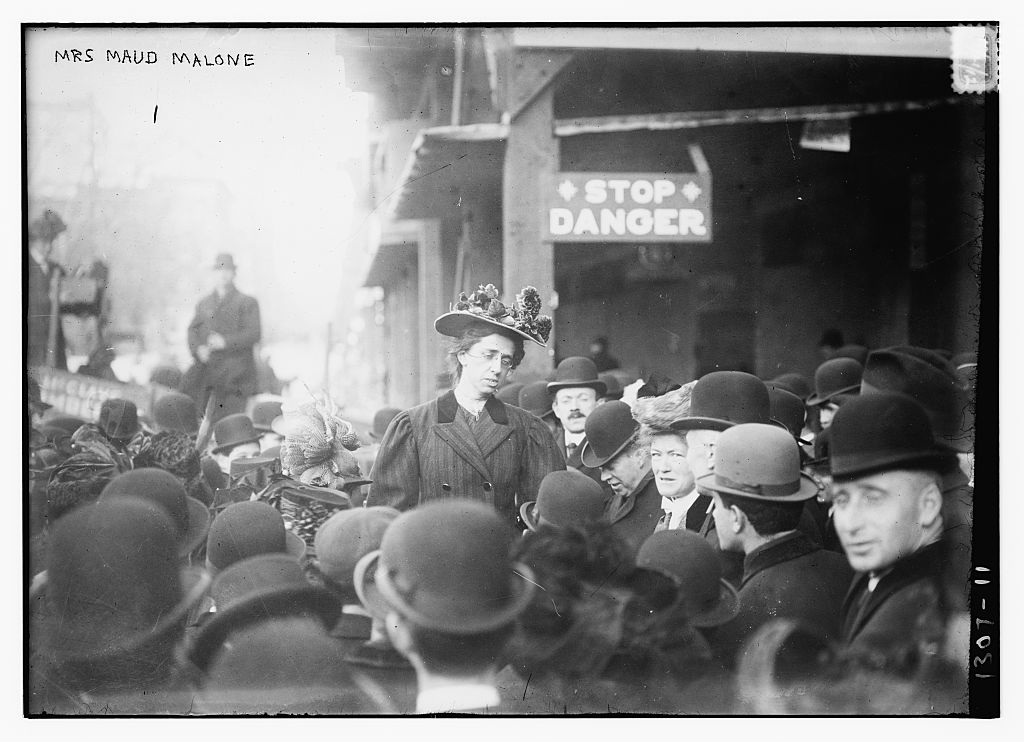

Image: Maud Malone speaks at the first outdoor meeting concerning suffrage, Decemer 31, 1907. Bain News Service collection, Library of Congress.

Maud belonged to several women’s clubs, where women debated all kinds of issues. She shared her idea of speaking publicly on the street. At first, women club members refused, saying they would lose all respectability. But soon, women suffragists in Britain began holding their own street meetings. By 1907, Maud convinced her fellow members of the Harlem Equal Rights League to hold open-air meetings about suffrage, like their sisters in Great Britain. They would collect signatures calling on New York state legislators to grant women the right to vote.

Maud’s first open air suffrage meeting took place December 31,1907 in Madison Square Park. She, along with British reformer Bettina Borrmann Wells, collected hundreds of signatures. Reporters admired how Maud used humor and sarcasm in question and answer sessions with the mostly male audience.

“Do women know enough to vote?” asked one man.

“I guess they know as much as any of you men.”

“How do you know?”

“Why, I can tell by looking into your faces!” (Cheers.)

The open air meeting was followed by others. With more women choosing to participate after all, Maud introduced another new tactic from Britain: the parade.

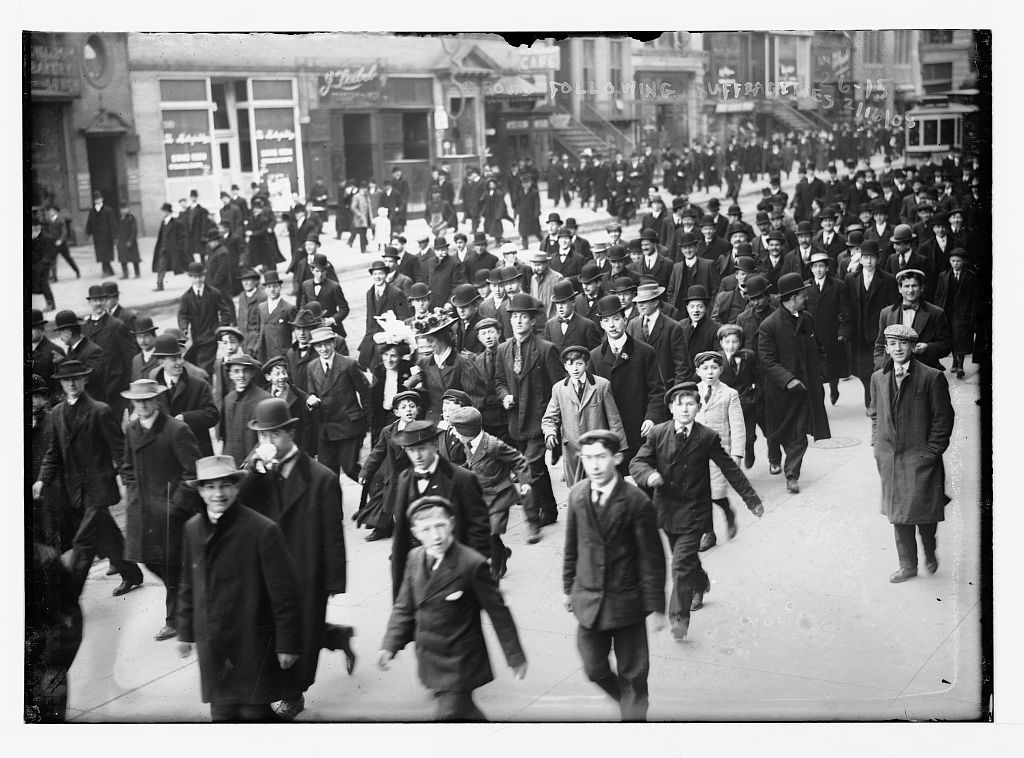

At the time, suffrage leaders like Carrie Chapman Catt strongly opposed the idea. But the first parade on February 16, 1908 attracted about 2,000 men. They even defied a police ban, strolling up Broadway from Union Square to 23rd Street to a suffrage meeting, where the crowd stretched into the street.[2] There were no arrests. Unlike the violent British rallies, reporters saw Americans having fun.

Image: The crowd in the suffrage parade up Broadway on February 16, 1908. Maud Malone is the taller woman near the center of the photo. Bain News Service collection, Library of Congress.

Soon, suffrage parades were everywhere. “Since we have become more militant,” she said later, “we have won our greatest victories.” In 1915, New York state voters rejected granting women the right to vote, but two years later, voters had another chance. This time, voters approved women suffrage. The 1917 victory in New York state was a major catalyst in granting women the right to vote nationally three years later.

Meanwhile, Maud had moved on to other tactics. Now she was questioning politicians during their speeches. Sometimes she was arrested. In 1917, she was among the suffragists who picketed the White House. When organizations failed to live up to her passion and ideals---even groups she had founded---she quit them. When she left her own Progressive Women’s Suffrage Union, she said, “The movement to be truly progressive should recognize no prejudice of race, color, difference in clothes or creed, whether religious or economic…” Politically, she kept moving ever leftward in search of others who agreed with her brand of militancy.

When not working for woman suffrage, Maud worked for the New York Public Library. In 1917, she was a founding member of the Library Employees' Union, the first labor union in the United States representing public library employees. Maud was just as outspoken in her union activity as she was elsewhere, using suffrage tactics to advocate for better working conditions -- particularly for women library workers. In 1932, the New York Public Library fired her. She later worked as librarian for the Daily Worker newspaper. Maud died in 1951.

Maud Malone was an innovator who refused to compromise her ideals. Sadly, she has been forgotten in the history of women suffrage. As we commemorate the Centennial of the 19th Amendment, we should remember that change belongs to the risk-takers, like the fighting Malones. Sometimes, they remain on the outside, even as they open the doors for others to walk through.

The series Maud Malone: New York City Librarian and Suffrage Powerhouse has more information about this remarkable person.

Notes:

[1] The Cooper Union in Manhattan was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on July 4, 1961.

[2] Union Square was designated a National Historic Landmark on December 9, 1997.