Last updated: May 31, 2025

Person

Jens Jensen

The Clearing Folk School

"Apostle of the Dunes"

“In the primitive we find it a mystery that we cannot solve and brings to us something deeper, greater and more beautiful than the human mind can create, and so makes us better beings.”

Chicago landscape architect Jens Jensen espoused the virtues of a design philosophy based on the use of regional ecology, materials, and native plant species.

In 1883, a young Jens Jensen imigrated to the United States from Denmark; he tried farming in Florida and then Iowa before moving to Chicago in 1885 to work for the West Park Commission, which managed all parks on Chicago's West Side. Jensen promptly fell in love with the Midwest's prairie landscape. Although some thought that prairie was boring, monotonous, and ordinary, Jensen saw great beauty in the tree-filled groves, long winding rivers, natural rock formations and waterfalls, and the flat stretches filled with colorful native grasses and wild flowers.

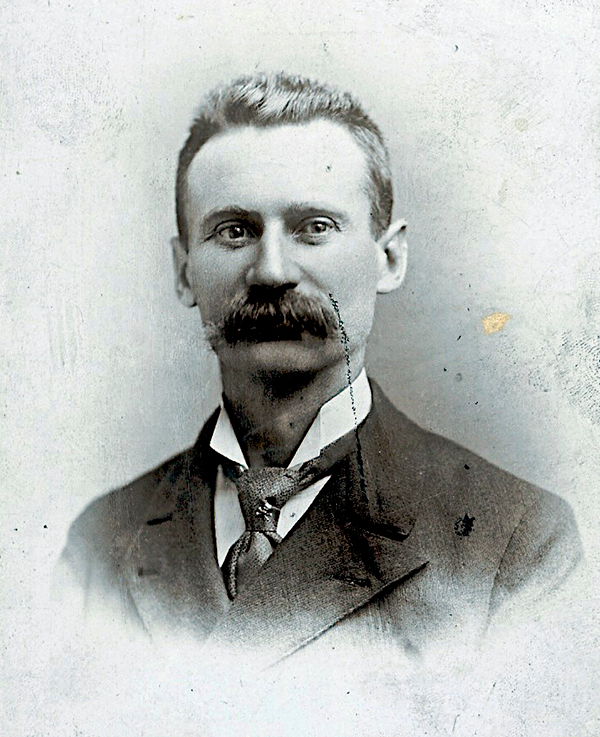

Image caption: Jens Jensen circa 1895 (The Clearing Folk School)

While he was at the commission, he designed several park grounds with non-native plants, which tended to fare poorly in Chicago’s climate. He tried a new approach in 1888 using only native, transplanted wildflowers to develop what became known as the “America Garden” in Union Park (the America Garden no longer exists). The success of the native garden led him to become a park foreman, a position he held for several years.

As early as the 1880s, commercial interests began exploiting the lakeshore. Sand mining companies hauled huge quantities of sand from the dunes for use in Chicago landfills and building industries. In one unpopulated area near the mouth of the Grand Calumet River, the Illinois Steel Company, a subsidiary of U.S. Steel, purchased land in 1905 and began constructing a new steel manufacturing plant the following year. A new community, named after the corporation's finance committee chairman, Elbert H. Gary, thrived nearby. Woodlands, swamps, and dunes were eradicated to accommodate the new structures.

“With the density of population comes destruction of the beauties of out-of-doors, and when they are crushed out, it is observed, civilization declines.”

By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, it was apparent that the urban industrial sprawl from Chicago would continue its rapid encroachment on the Indiana Dunes. Hoosier Slide, just west of Michigan City, at 200 feet high was the largest sand dune on Indiana's lakeshore and a popular attraction for climbing and sliding. In twenty years, the Ball Brothers of Muncie, Indiana, manufacturers of glass fruit jars, and the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company of Kokomo, Indiana, carried Hoosier Slide away in railroad boxcars. Northern Indiana Public Service Company (NIPSCO) bought the denuded site to build a power generating station.

Drawing on inspiration from the Midwest landscape, Jensen was the banner carrier for the Prairie Style of landscape design where regionalism was the driving force behind design aesthetics. His designs, characterized by recreations of Midwestern prairie and woodland plant communities, were embellished with features of water and stone. Native plants were grouped and massed in their ecological habitats that typically featured an overstory of trees and an understory of associated shrub and groundcover plantings. Plants controlled views and movement by creating mystery that enticed users to move through the space. The “long view” encouraged the viewing, from one end to the other, open linear spaces bordered by trees and shrubs. His landscapes displayed horizontal layers of stonework reminiscent of rock outcroppings, and large flat water features he termed “prairie rivers.” His signature council rings were designed to encourage discussion and storytelling. Having grown extremely popular, he was commissioned to construct roadway, park, school, and estate projects throughout the Midwest.

Regarding Jensen’s use of native plants, an article in Prairie Gardening from 1915 noted that:

“the primary motive was to give recreation and pleasure to people, but the secondary motive was to inspire them with the vanishing beauty of the prairie.”

In the early 1900s, many natural areas were being destroyed due to the rapid growth of cities and towns. Jens Jensen worried that people were losing touch with nature. He feared that living in an entirely artificial environment would leave humanity spiritually, emotionally, and intellectually empty. Through a variety of ways, Jensen promoted an appreciation for the outdoors to emotionally and spiritually uplift city dwellers. Many of these efforts were geared toward children, such as the addition of children's gardens to several parks. Through these gardens, he believed children would grow up to respect, preserve, and love nature.

In 1904, he collaborated with Dwight H. Perkins to publish an influential report on the need to preserve forests around Chicago and develop neighborhood parks in the congested city. His work led to the establishment of Illinois' state park system, one of the oldest in the country. His efforts also helped form the Cook County Forest Preserves in 1914, one of the oldest and largest county forest preserve systems in the country.

He returned as general superintendent of the West Park Commission in 1906 and redesigned Garfield, Douglas, and Humboldt parks using native wildflowers and plants. He also designed Columbus Park.

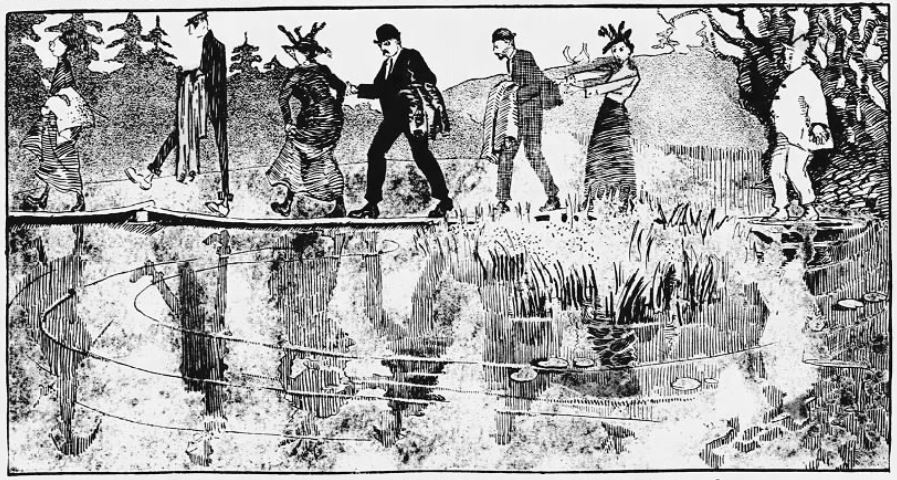

From Gary to Michigan City, industry ringed Indiana's lakeshore. Local residents and some Chicagoans recognized the threat and organized to meet it. Because he appreciated the native environment of the Midwest and was willing to act on his convictions, Jens Jensen emerged as a leader of the conservation movement. To make Chicagoans aware of the beautiful countryside outside of the city and generate public support for conservation, Jens Jensen and some influential friends sponsored "Saturday Afternoon Walking Trips" beginning in 1908. They took turns leading groups to natural areas outside of the city. Often, more than 200 people participated in these excursions. Members took walking trips to natural sites threatened by development.

Image caption: Participants in a Saturday Afternoon Walk traverse a prairie stream in their formal attire circa 1909. (Jens Jensen Collection, Sterling Morton Library, Morton Arboretum)

The popularity of the weekly event prompted Jensen, Thomas W. Allinson, and Henry C. Cowles to form the Prairie Club of Chicago in 1911. All three men served on the club's conservation committee with industrialist Stephen T. Mather, future first Director of the National Park Service. For the Midwest, the Prairie Club became the counterpart of the Appalachian Trail Club in the East and the Sierra Club in the West. Jensen had studied the Indiana dunes and led 300 members to see the site. The Prairie Club was the first group to propose that a portion of the Indiana Dunes be protected from commercial interests and maintained in its pristine condition for the enjoyment of the people. The following year club president Jens Jensen purchased "the Beach House" east of Mount Tom in Tremont where the group could assemble and strategize. For thirteen years, Jensen, the "Dean of American Landscape Architects" and Superintendent of the Chicago Park System, spoke throughout the region promoting the dunes and earning for himself the title "Apostle of the Dunes."

Image caption: "Close to Nature and a Plunge in the Pond" (Illustration from Chicago Tribune, May 23rd, 1909)

Also in 1913, the Prairie Club built a beach house on the dunes in Tremont, Indiana and produced and performed a small masque, an outdoor drama, called "The Spirit of the Dunes."

That same year, Jensen formed "Friends of Our Native Landscape," an organization devoted to saving natural areas, the "spiritual power in the American landscape." The group joined the Prairie Club for the weekend walks in the dunes.The first meeting was scheduled to take place in June at a threatened white pine forest near Oregon, Illinois. Jensen thought that outdoor drama would be a compelling way to interest people in conservation.

Image caption: A fairy ring dance performance at the Indiana Dunes circa 1913. (Jens Jensen Collection, Sterling Morton Library, Morton Arboretum)

Jensen was so pleased with the masques that he began including "player's greens," outdoor theater spaces for drama and music, in his designs for private residences and public parks. In his Columbus Park design, Jensen made certain that visitors to dusk performances got to see the sun set over the park's trees and the players illuminated by the rising moon. He envisioned the Columbus Park lagoon as the site of water pageants and designed it with audiences in mind, as well.

The idea of establishing a park in the Indiana Dunes germinated for several years, and the concept blossomed in the spring of 1916. Rumors circulated about the impending dredging of Fort Creek at Waverly Beach to accommodate Lake Michigan ships loading sand directly from railroad cars. Many were convinced Mount Tom was to go the way of Hoosier Slide. When Prairie Club members staged their annual picnic at the Beach House, they decided to take the offensive against the industrial interests despoiling the Indiana Dunes. They voted to form the National Dunes Park Association (NDPA) to promote the establishment of a national park on Indiana's lakeshore. On July 16, a mass meeting at Waverly Beach to inaugurate the effort resulted in three special trains from Chicago carrying 5,000 people to the dunes. With a theme of "A National Park for the Middle West, and all the Middle West for a National Park," a principal goal was to raise money to buy enough duneland to turn over to the Federal Government for a national park. Elected officers of the NDPA were Armanis F. Knotts, Thomas H. Cannon, and Mrs. Frank (Bess) Sheehan. On the board of directors were Jens Jensen, Henry C. Cowles, John O. Bowers, and George M. Pinneo.

The popular appeal of the NDPA's message was phenomenal. Less than two months later, on September 7, U.S. Senator Thomas Taggart (Democrat-Indiana) successfully presented Resolution 268 before the Senate calling on Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane to explore the feasibility of obtaining segments of three Indiana counties for a Sand Dunes National Park.

The following spring, the National Dunes Park Association organized a pageant in the dunes entitled "The Dunes Under Four Flags." This enormous production involved a cast of around 1,000, and estimates of attendance swell to 20,000. Following this surge in popularity, Stephen Mather organized a propsal for a national park at the Indiana Dunes.

In October of 1917, Stephen Mather held a hearing on a proposed "Sand Dunes National Park" in Chicago's Federal Building. Mather said:

When I went down to the dunes some years ago, I think I was under the guidance of my friend, Mr. Jens Jensen. There were several of us in the party and we climbed over some of the hills there and down in the valleys, perhaps not with the same enthusiasm at first that Mr. Jensen did, but after he had gotten us well into the spirit of it, we forgot we were tired, and followed him wherever he offered to lead us. I think, therefore, that it will be very appropriate for him to start right now and lead us on another trip, speaking, as he will, on behalf of the Chicago City Club, and also on behalf of the Friends of Our Native Landscape, of which he is president. We will take pleasure in listening to Mr. Jensen. [Applause.]

Image caption: Jens Jensen circa 1905 (The Clearing Folk School)

Mr. Jensen then gave the following remarks:

Mr Secretary, ladies, and gentleman, it seems to me… that there should be no question at all about this dune park proposition. Just think of us poor prairie folks, who have not the Adirondack Mountains, as has our good friend from New York, and who have not the mountains of California, as has our good friend Mr. Mather. In fact, the only thing in the world that we have that has any similarity at all to the Adirondacks and the Rocky Mountains is our dunes over in Indiana. The 200 feet of Mount Tom look just as big to me as the Rocky Mountains did when I visited them some years ago, and bigger to me, in fact, that did the Berkshires when I made my pilgrimage to those wonderful hills of Massachusetts. [Applause.] We need the dunes. If you had been with me yesterday and stood on top of one of the great blowouts, as we term them, and looked into the golds, the reds, the soft tinges of brown, and the soft shades of green that were just visible in some of those dune woods, you would have come back to your home saying, “We need the dunes; we can bever do without them. We who live in the midst of this conglomeration of buildings, cement sidewalks, and stone pavements, how can we ever be without such a wonderful vision, a vision that we carry vividly with us until we can make our next pilgrimage?” If you had gone with me along one of the ancient trails, between Michigan City and Chicago, among those giant pines—I call them giant pines, because they are that way to me, and to all of us poor prairie folk in Illinois—you would have come back to your home saying, “Never, never must those wonderful pines be destroyed.” The whole city life of Chicago, and those people who live in our adjoining towns, as well as our good friends in Indiana, should become acquainted with that country in order that they may refresh themselves and revivify their souls.

It was many years ago that I made my first pilgrimage to the dunes. It was previous to the time our good friend Mather accompanied me. I can never describe to you the impression I received of my first visit; but I will tell you this, the impression I received yesterday, even after having gone through the dunes for more than 20 long years, was the greatest and most wonderful impression that I ever received there. I would give anything if I could only impart that wonderful impression, that wonderful feeling, to any one of you. It is something that will stay with me as long as I live. Those are the things for which the dunes stand and which make them of such value to us. There are lots of folk who say, “Well, so many of us do not see these wonderful things.” Oh, how materialistic we are. There is a soul in each of us and it only needs awakening; and when it is awakening then there will burst upon us the first realization of the wonderful beauty of the dune country…

What I want to impress on your minds is the beauty and grandeur of this dune country. There are no dunes in America like those over there. The dunes on the various ocean coasts, the dunes that are salt water dunes, are of an entirely different type. They totally lack the poetic inspiration those dunes of Indiana have. The salt breezes prevent a great deal of vegetation from growing, and therefore the ocean dunes are not covered with vegetation as ours are. They are not filled with the wonderful poetic inspiration of our dunes. They do not display the wonderful color effect you get these days down in our dunes, such as can not be found anywhere else in the world. Nowhere else can be found such a wonderful outburst of flora in the spring as is found in our dune woods, when they are covered with a blue sea of wonderful lupin, or phlox, or violets, or many other plants, all wonderful in their color display. Nowhere else can be found such a wonderful expression of spring. The other dunes do not have it. That is why our foreign friends must come to our dunes to find this wonderful poetic expression…. Our dunes are… poetic, they are beautiful, they are wonderful; they are just about the most beautiful and wonderful thing we have in the Middle West.

…Though we always talk so much about the wonderful national parks of the West, how many of us are ever able to make a pilgrimage to those parks? How many of us? What are we doing for the tens of thousands of people in this noisy, grimy, seething city, who need to revive their souls and to refresh the inner man as well as the outer? What are we doing for them? There is only one thing we can give them, and that is the opportunity to revive their souls in the outglow of beauty from the dunes over yonder on the shores of Lake Michigan. If we should permit that wonderful place to be sold for a “mess of pottage,” it would be one of the worst calamities that could befall us. Think of the good Indiana folk. The only outlet they have to Lake Michigan is right there, the only outlet that is left for them. That is the only breathing place they have on the shores of beautiful Lake Michigan, and there is nothing left to the great State of Indiana if that wonderful piece of country is done away with. Now, I am not going to tire you with my remarks any longer. I am just going to say one final word to you, and it is this: That it would be such a sad thing, indeed, for this great Central West if this wonderful dune country should be taken from us and on it built cities like Gary, Indiana Harbor, and others. It would show us to be in fact what we are often accused of being—a people who only have dollars for eyes. We are in duty bound to preserve some of the wild beauty of our country for our descendants. I thank you. [Applause.]

Jensen's efforts with the first conservation push in the Indiana Dunes and ties with Richard Leiber helped Bess Sheehan's efforts to establish an Indiana Dunes State Park. The establishment of a National Park Service unit would not be realized until 1966 following a 14-year battle led by Dorothy Buell and Senator Paul H. Douglas for land use along Indiana's shore.

Jensen founded a private practice in 1920, and he continued to design public and private gardens, each emphasizing natural elements found in the prairie. He designed gardens for four of Henry Ford’s homes in Michigan and Maine. Jensen’s work involved informal winding garden paths through organic or natural-looking landscapes with water features. Natural scenes were created by using local plants and materials, especially limestone slabs stacked into bluffs, walls, stream edges, and paths; all evoked the natural river systems of the Midwest

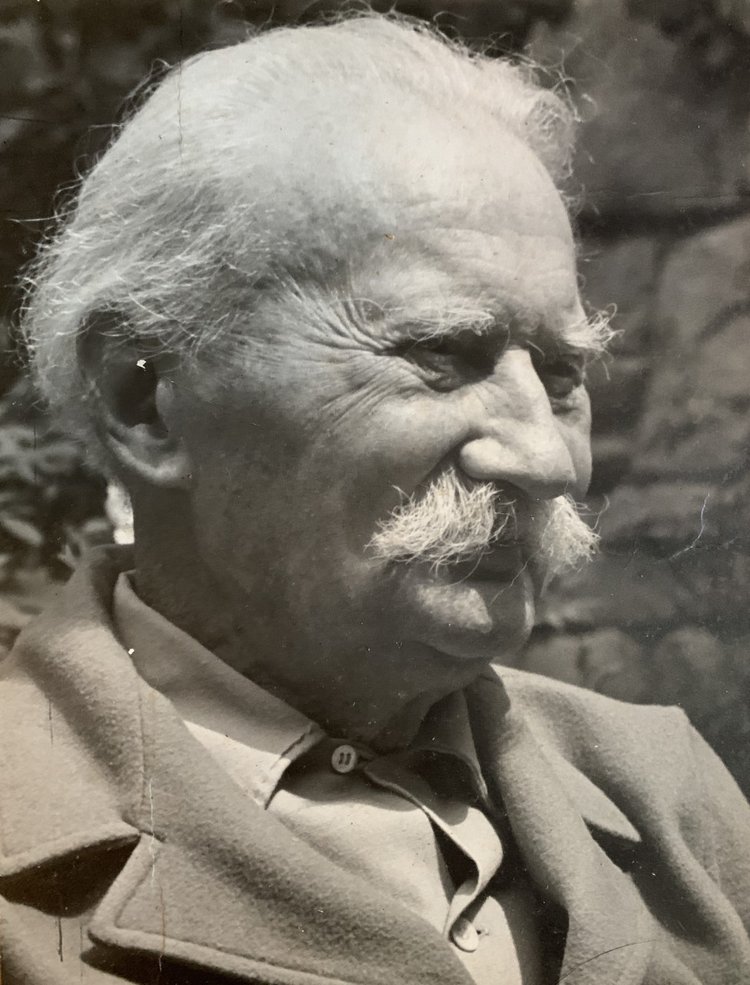

In his later years, Jensen retired to his summer property in Ellison Bay, Wisconsin. He helped establish many of Door County, Wisconsin's parks and the Ridges Sanctuary. Above all, he dedicated himself to creating a "school of the soil" where pupils could draw enduring values from rock, sun, water, and wilderness. In 1935, inspired by the folk schools of his native Denmark, Jensen founded "The Clearing," a hands-on school to promote natural landscape design and an ethic of conservation. Jensen directed the school until his death 15 years later, just after his 91st birthday. The Danish immigrant left his adopted nation both a rich legacy of beautiful landscapes and a challenge, to set aside sections of the wilderness so that future generations might study and love it.

Image caption: Jens Jensen circa 1945 (The Clearing Folk School)

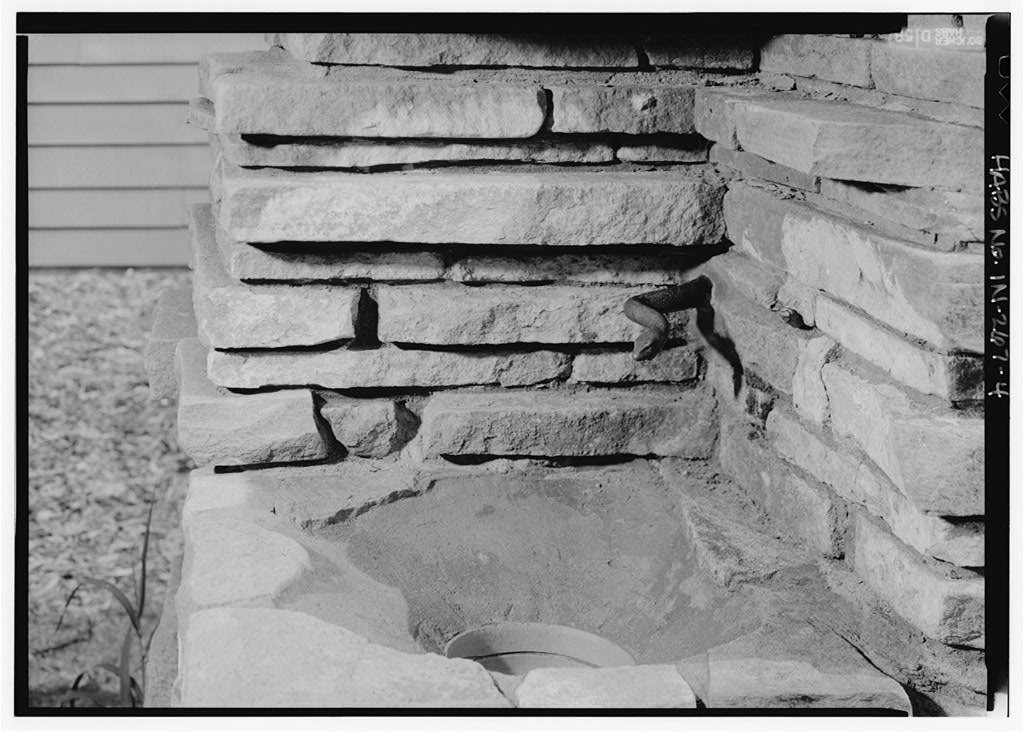

In 1932, the Priarie Club gifted a memorial fountain deisgned by Jensen to the Indiana Dunes State Park to honor the club's efforts in the area's preservation. The fountain exudes Jensen's Prairie Style, featuring stacked, linear blocks of stone and a bronze snake emerging from a crevice. Today it stands outside the entrance of Indiana Dunes State Park's Nature Center.

Image caption: Close-up view of Jensen's fountain within Indiana Dunes State Park circa 1933. (Library of Congress)

Jensen penned the introduction for George Brennan's 1923 Wonders of the Dunes, writing:

Just a little bit beyond our eastern gateway lies the Dune country,— the vast garden of mid-America. Within easy each of millions, it has remained practically unknown. But have we not always been blind to the great treasures of the out-of-doors? Man allows himself in his own conceit to do things that make him forget he is an inseparable part of nature, and that, in wild beauty untrampled by his kind, he may find himself.

The Dune Country possess all the charm, mystery and beauty that primitive America has to offer anywhere. Countless ages are written in its sand-hills, and its to-morrow is in the making. High above the Dune woods loom the gray heads of the Dune giants, where the west wind and the sand play tag over carpets of bearberry, among gnarled oaks centuries old. Farther down, in the blowouts and on the Dune meadows, friends of pleasanter climes, like the cactus, have found shelter and protection far away from their ancestral homes. Here the North, the South, then East and the West meet in cheerful rivalry, each selecting as its own, the place to which it is best adapted.

It is a native arboretum of vast instruction to those who seek knowledge in the out-of-doors of plant and animal life. It is a shrine for solace and quietness in contrast to the turbulent life of the great city.

Here you will find intimate beauty and hidden treasures of the flower world, besides great dramatic expressions in the moving sands and the forest-covered Dunes of long ago.

Here you may wander among buried woods of unknown ages and sit in contemplation on lands of to-day. Trails of bygone times, blazed by Indian and pioneer, and shaded by a host of centenarians, give thought for reflection and historic reminiscence.

Magic are the Dunes where they meet the sea—the sea that bore them. There is an ocean-like grandeur in the broad stretches of beaches; the waves, chasing one another in madness, pitch high; the west wind roars and the sand blizzard rules ; seagulls fill the air like giant snowflakes. Then the Dune country is in its making, and a grand drama is enacted on those Indiana shores.

Spring, when dogwood and shadbush vie with each other in garlanding hills and valleys; when violets and columbine cover the forest floor with a carpet for fairies only to tread upon; when seas of lupines invade the Dune meadows, and the love songs of mating birds fill the air!

Summer, in deep green, with shadows refreshed by cooling breezes from the lake.

Autumn, when the Dune partakes of every ray in the rainbow; when sand-cherries set the beaches aflame; and the sand and wind-beaten pines look at it all in amazement, reflected in the turquoise sea.

Winter, it its white mantle of snow, a fairy-land marked by the footprints of its native inhabitants.

A people possessing love for this country will never sacrifice this out-of-doors shrine. With zealous eyes they watch over it and guard its destiny far into the to-morrow.

In the 1941 book "Outdoors with the Prairie Club," Jensen is quoted saying:

Nothing of real value is won without effort and struggle. To lie down upon our laurels is futile; continuous effort is required to hold what has been won. There are new fields to be discovered, new laurels to win. Conservation is still in its infancy. A real love and understanding of the beauty and wonders of the earth we inhabit is an essential part of a high culture. It is not a mere sport, but a real idealism—a profoundly spiritual and cultural ideal.

Sources

- Cockrell, Ron; A Signature of Time and Eternity: The Administrative History of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Indiana, National Park Service, 1988.

- Morse Dell Plain House and Garden, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1995.

- Teaching with Historic Places; Chicago's Columbus Park: The Prairie Idealized, National Park Service, 2002.

- William Whitaker, Landscape and House, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1999.