|

National Park Service

The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb A Submerged Cultural Resources Assessment of the Sunken Fleet of Operation Crossroads at Bikini and Kwajalein Atoll Lagoons |

|

CHAPTER FOUR: SITE DESCRIPTIONS

James P. Delgado and Larry E. Murphy

INTRODUCTION

During two field sessions at Bikini and Kwajalein, eleven shipwrecks from the Able and Baker tests were surveyed. The results include graphics, photographs, and narrative site descriptions included in this report, as well as several hours of video footage. Time spent underwater on each site was limited by both field session lengths and diving constraints. Most dives were decompression dives between 100 and 180 feet in depth. Typically, two dives were done each day, and in the two sessions which cumulatively totalled four weeks, there were 24 diving days.

In addition to site descriptions, which are the principal archeological fieldwork products, we evaluated the Bikini wrecks in terms of site formation processes. Rather than emphasizing the unique nature of wreck events caused by an atomic blast, we take the position that whatever the agency of destruction, ships are damaged and sunk by forces governed by physical processes that are repetitive, often quantifiable, and that ultimately may be predictable. In addition to describing the target ships and evaluating their current condition as the result of a unique set of historical circumstances that may never be repeated, we present the analysis in terms that may be useful for comparisons with other wreck processes. A comparative approach is taken for those ships sunk by the same blast, between categories of ships and between ships sunk by the two blasts. The site descriptions pay particular attention to variables of ship class, proximity, and orientation to the blast, pre-blast vessel condition and alterations. We have also included contemporary observations from immediate post-blast vessel evaluations as a control for natural deterioration resulting from submersion for nearly 45 years.

|

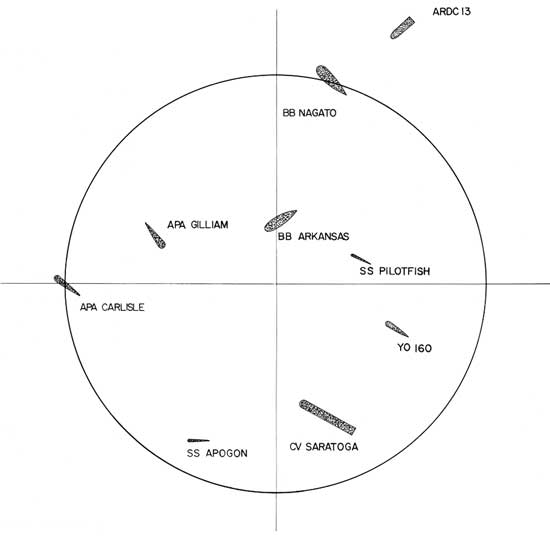

| Actual positions of the sunken ships at Bikini, as plotted by the U.S. Navy, 1989. (Redrawn by Robbyn Jackson, HABS/HAER) (click on image for a PDF version) |

This particular approach incorporates into the site description some of the remarkable amount of quantified data collected by the numerous test-instrument arrays. The Able test included 5,000 pressure gauges, 25,000 radiation-measuring instruments, 750 cameras, and four television transmitters within and around the target array. [1] Eighty percent of the instruments were recovered after each test from the sunken test ships. [2] These data, recently declassified, offer a rare chance to observe structural hull damage that can be attributed to measured peak-pressure waves of known duration. These observations provide a comparison against which other wreck processes, whether conventional explosives or natural effects, can be measured for steel-hulled shipwrecks.

The discussions in this chapter follow the categorical sequence of Pre-Test Alterations, Immediate Post-Blast Observations, and 1989/90 Site Descriptions. Pre-Test Alterations includes the recorded changes to each vessel in preparation for Operation Crossroads. In order to make the atomic test reliable, the vessels had to be in good repair. Most test vessels were recent combat veterans and required some repairs. Post-Blast Observations, like Pre-Test Alterations, are derived from historical records. This section presents both surface observations of each ship's sinking and underwater observations made by divers examining the wrecks shortly after each blast. Apparently there were two diving evaluations made by the Navy, one soon after the blast and another a year later. Unfortunately, with the exception of Saratoga, most of the detailed descriptions of the 1947 dives on these vessels are not available; only general descriptions were microfiched, the rest are missing from the archival record.

Two target vessels were lost in shallow water inside Kwajalein Atoll lagoon. The German cruiser Prinz Eugen and an infantry landing craft, LCI-327, were lost to capsizing or grounding and left in place. All but nine of the other target vessels not sunk in Bikini Lagoon were scuttled in deep water. This leaves a group of 21 wrecks associated with Operation Crossroads accessible to divers at Bikini and Kwajalein atolls. Nine were dived and assessed during two field seasons by the NPS; two others were ROV dived by the Navy and subsequently assessed by the NPS.

This Site Descriptions section contains the 1989 and 1990 fieldwork observations as well as observations made by divers and through use of surface-monitored Remote Operated Vehicles. Each site discussion is a composite drawn from direct observations, video, photographic and field illustrations. The amount of time spent on each site was variable, which is reflected in the amount of detail in each site discussion.

RECONSTRUCTING THE NUCLEAR DETONATIONS

The "nominal yield" of the two plutonium, implosion-core Mk III "Fat Man" bombs detonated during Operation Crossroads has been variously estimated in secondary source histories to have been between 20 to 23 kilotons, or a force equal to 20,000 to 23,000 tons of TNT. The formerly classified official analysis of the "Able" detonation of July 1, 1946, noted that one measuring technique indicated that the bomb's yield was 19.1 kilotons. [3] The "Baker" detonation of July 25, 1946, was noted to have yielded approximately 20.3 kilotons, described as a "normal" yield for "an atomic bomb of the Nagasaki type." [4]

The Able Detonation

The proximity (VT) fuze of the "Able" bomb was set for an altitude of 515 feet over the ocean surface. Even though the bomb missed the intended target ship, USS Nevada, by 710 yards, it detonated close to the set altitude, at 518 feet, 50 yards off, and slightly to starboard, of USS Gilliam. [5]

The firing of the weapon caused the fissionable material in the bomb to become supercritical, and a self-sustaining chain reaction was initiated. The fission process released the energy equivalent to approximately 20 kilotons of TNT before the bomb was quickly blown apart and fission was no longer possible. A luminous mass known as the "ball of fire" was formed. The ball of fire emitted thermal radiation that started fires as far away as 3,700 yards. [6] The thermal radiation accounted for 35 percent of the total energy released in the detonation. The ball of fire continued to expand, touching the water, as vapor from the detonation formed a reddish-brown cloud rich in nitrous acid and nitrogen oxide, which climbed at a rate of 200 miles per hour. At 0.5 seconds after the detonation, the fireball was nearly 1,500 feet in diameter.

Immediately after detonation, a high-pressure wave was created that swept about 750 feet ahead of the fireball. This "blast wave" with its shock front, accounted for 50 percent of the total energy released by the bomb. At 1.25 seconds, the shock front had moved out more than a third of a mile, and had struck the lagoon surface. This created a reflected shock wave that travelled up to collide with the initial shock wave, fusing with it to form a single, reinforced "mach effect" front that generated up to 16-pounds-per-square-inch peak overpressure. [7] The mach front continued to grow, so that three seconds after detonation, it was nearly a mile from the zeropoint and 185 feet high, creating winds at the front of 165 miles per hour. [8]

Ten seconds after detonation, the mach front was 2.5 miles from the zeropoint, moving at 40 mph with a peak overpressure of one psi. The blast effect of the bomb at this time was effectively over, as the hot, gaseous ball of fire rose, drawing up air and producing strong air currents, or "afterwinds" that sucked up water and debris to form the stem of the characteristic "mushroom cloud." [9] Only 30 seconds after detonation, the cloud was about a mile and a half high. Ten minutes after detonation, the water sucked up into the cloud or vaporized by the ball of fire was released when a light, radioactive rain fell.

Apart from the initial release of nuclear radiation, which accounted for five percent of the total energy expended, residual radiation near the point of detonation was reported to be minimal, which was attributed to the carrying up by the afterwinds of the radioactive materials into the cloud and their distribution into a diffuse, light fallout that did not, for the most part, land on the target fleet.

1946 "Able" Damage Assessments

A summary of damage to the target ships was prepared by Joint Task Force One. The following discussion is drawn from that document and not from the archeological record prepared by the NPS.

The worse damage was done to ships within a thousand-yard radius of the zeropoint. Five ships were sunk: Gilliam (50 yards from the zeropoint); Sakawa (420 yards); Carlisle (430 yards); Anderson (600 yards); and Lamson (760 yards). Additionally, six other target vessels were "immobilized" by blast damage, and another eight suffered "short- or long-term serious loss of military efficiency" by having their boilers, radio, or radar and fire control systems disabled. These were Skate (400 yards); YO-160 (520 yards); Independence (560 yards); Crittenden (595 yards); Nevada (615 yards); Arkansas (620 yards); Pensacola (710 yards); ARDC-13 (825 yards); Dawson (855 yards); Salt Lake City (895 yards); Hughes (920 yards); Rhind (1,012 yards); LST-52 (1,530 yards); and Saratoga (2,265 yards). Additionally, four ships suffered "short- or long-term moderate loss of military efficiency": Talbot (1,165 yards); Barrow (1,335 yards); Pennsylvania (1,540 yards); and New York (1,545 yards). Based on these reports, Joint Task Force One concluded after plotting the actual damage and determining its relationship to the structural strength of the specific ship types and methods of construction, that the range of damage was "very serious" to 900 yards, "serious" to 1,000 yards, "moderate" to 1,300 yards, and "slight" to 1,500 yards. [10]

The worse damage from the blast was that suffered by vessel superstructures. Hull damage, including decks, sides, and bottoms, was next in severity, followed by damage to masts and stacks. The worse hull damage was that done to Gilliam, which was described as "badly ruptured, crumpled, and twisted almost beyond recognition." [11] Gilliam sank within a minute. The other attack transport, Carlisle, sunk, was dished, and had hull breaks. However, the transport Crittenden, 165 yards farther out from the zeropoint than Carlisle, survived sinking, although it suffered "severe dishing and deflection of the deck." Carlisle's sinking was attributed more to its beam-on orientation; hence Crittenden's "bow-on orientation may have saved her from being sunk." [12]

The loss of Sakawa, which sank in 25 hours from tears in the stern plating, was attributed to its "considerably lighter construction," as opposed to the two U.S. cruisers moored nearby, which suffered dished decks and stacks and superstructure damage. [13] The destroyers Anderson and Lamson, two of three destroyers anchored within the thousand-yard radius of the zeropoint, sank because of extensive hull damage. USS Hughes, at 920 yards, was dished but survived. Three other vessels suffered major damage without sinking. The light carrier Independence's hull was "blown in and there was buckling of bulkheads." Additionally, the flight deck was "badly warped and buckled, and the sides enclosing the hangar deck were blown through." [14] USS Skate suffered serious damage which prevented the submarine from submerging, including a bent conning tower and a "badly stripped and crumpled superstructure." YO-160's concrete hull was broken and spalled, exposing bent reinforcing bars, its concrete deckhouses were smashed, and all of the wood in the vessel was burned by a thermal-radiation-induced shipboard fire. [15]

Flash scorching on painted surfaces was found on vessels up to 3,700 yards distant from the zeropoint. Fires were started on several vessels, usually in cordage, canvas, or burlap wrappings on exposed Army test items, notably on USS Saratoga, the most distant vessel (2,265 yards) from the zeropoint to suffer any Able damage. Fires aboard USS Anderson probably exploded shipboard ordnance, hastening its sinking. The only fuel oil fire was started aboard Sakawa.

The Baker Detonation

The Baker bomb was detonated by Los Alamos scientists inside its steel and concrete caisson, suspended 90 feet beneath LSM-60, and approximately 90 feet above the lagoon bottom. [16] Energy release was similar to the Able shot. A fireball was formed that illuminated the water with an orange-white light for a few millionths of a second before the high-pressure gases of the ball erupted to the surface. The shock wave formed a "blast slick" of white water on the surface, emanating out from the zeropoint in a "rapidly advancing circle" formed by the hurtling of small water droplets short distances into the air. [17] Immediately, within four millionths of a second, the gas bubble burst into the air, throwing up a mound of super-heated steam and water called the "spray dome," at a rate of 2,500 feet per second. [18] The spray dome climbed into a column in which the water in the center moved faster than the water farther out, at a rate estimated at 11,000 feet per second. This formed a hollow center in the column that acted as a chimney for the hot gases and superheated steam from the now nearly exhausted fireball to climb, carrying excavated lagoon bottom and radioactive products up to form, with water vapor, a cauliflower-shaped mushroom cloud. [19] At the same time, the condensation of the water formed a vast "Wilson Cloud" around the column 18 seconds after detonation, which dispersed into a dissipating ring of clouds that vanished after 30 seconds.

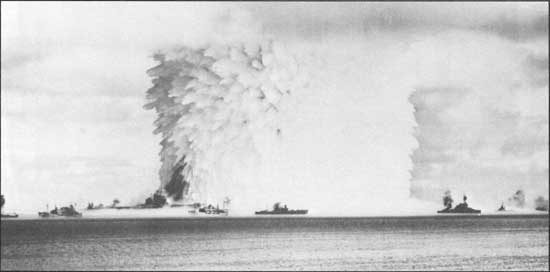

|

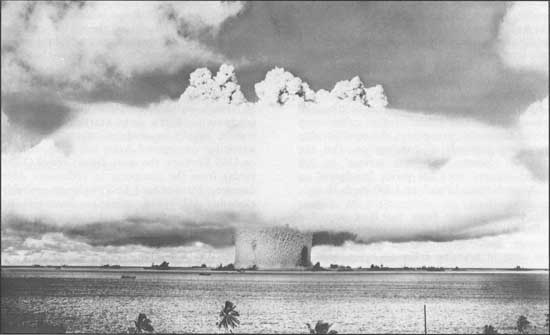

| The most famous photograph of Baker. The dark spot in the column marks the position of the capsizing Arkansas. Crossroads mythology mistakenly insists this photo shows the upended form of the battleship. (U.S. Naval Institute) |

The height of the column and cloud, containing some 2,000,000 tons of vaporized and boiling water (estimated at four cubic feet of water per thousand cubic feet of column and weighing at least two million tons), was 4,100 feet at 10 seconds after detonation, and 7,600 feet at 60 seconds. [20] At that time the stem radius was 975 feet in diameter, formed by 300-foot-thick walls of water with a 75-foot-diameter hollow stem. [21] The column also contained approximately 2,000,000 tons of lagoon bottom from a crater nearly 700 yards in diameter and 20 feet deep. The blast generated a seismic effect equal to an earthquake measuring 5.5 on the Richter scale. Ten percent of the energy released by the bomb was represented in the formation of the column and crater. [22]

The peak pressure wave lasted two milliseconds. The peak overpressures, recorded at a 90-foot depth, were considerable. At 835 feet from the zeropoint, the peak overpressure was 7,000 psi. Other readings were 5,900 psi (928 feet); 5,200 psi (996 feet); 4,400 psi (1,084 feet); 3,200 psi (1,278 feet); 2,300 psi (1,554 feet); 1,400 psi (2,060 feet); 800 psi (3,040 feet); 560 psi (3,700 feet); and 330 psi (5,000 feet). [23] It was later found that the ships shielded some of the blast. The underwater pressure on the remote sides of hulls was measured at 40 percent of those on the exposed sides. [24] Peak pressures were also recorded in the air that were equal to a 4-kiloton air or surface burst. The pressures measured in the air were 16 psi at 550 yards, diminishing rapidly to 9.6 psi at 650 yards, 6.6 psi at 800 yards, 4.8 psi at 100 yards, 3.8 psi at 1,200 yards, and 2.8 psi at 1,500 yards. [25]

The velocity of the pressure wave was the same in the water and in the air: at two seconds the shock front had travelled two miles from the zeropoint. Another effect of the shock front and the eruption of the fireball was the creation of a series of waves that moved at 45 knots. At seven seconds after detonation, a 94-foot-high wave passed the thousand-yard mark. It was followed by a 47-foot wave at 2,000 feet at 20.5 seconds, and a 24-foot wave at 4,000 feet at 47.5 seconds. These were the only three waves of height. Four lesser waves followed, diminishing to a nine-foot wave at 12,000 feet 156 seconds after detonation. The nearby islands of the atoll, notably Bikini, were washed by 15-foot breakers. [26] The creation of these waves accounted for one percent of the bomb's total energy.

A "base surge" also emanated out from the column as it collapsed. "This doughnut-shaped cloud moving rapidly out from the column...is essentially a dense cloud of water droplets, much like the spray at the base of Niagara Falls...but having the property of flowing almost as if it were a homogeneous fluid." [27] Moving at 45 mph, the base surge was 800 yards distant from the zeropoint and a thousand feet high. The base surge contained many of the bomb material's radionuclides as well as radionuclides produced because of activation of the sea water, lagoon sand, etc. It has been estimated by one expert that as much as 50 percent, and no less than 10 percent of the radioactive material remained trapped in the seawater. [28] Radiation levels were measured near the point of detonation at the surface of the water at more than 10,000 Roentgens, or at an amount variously estimated to have been equal to placing 2,500 to 8,300 tons of radium at the zeropoint. [29]

A fatal dose of radiation is generally assumed to be 400 Roentgens per 24 hours. Personnel on ships within 700 yards of the zeropoint would have received that fatal dose in 30 to 60 seconds. A dose 20 times fatal--8,000 Roentgens--would have been received in the first hour. At 7,000 yards, the fatal dose was administered in seven minutes, while at 2,500 yards, a fatal dose would have been accumulated in three hours. Radiation levels on the ship's decks fell to 65 Roentgens per 24 hours four hours after the blast, and to .1 Roentgens per 24 hours by five days after the blast, in large part because of radioactive decay and the diffusion of radioactive materials by convection and current. [30] Yet four- to eight-inch-thick contaminated sediments from the 50,000 cubic yards of bottom excavated from the crater that were estimated to have fallen back in the lagoon demonstrated "high" readings six days after the blast. Similarly, "a number of vessels were covered with contaminated coral sand which had been sucked from the bottom of the lagoon" and deposited by the base surge. [31]

1946 "Baker" Damage Assessments

The "Baker" detonation sank nine vessels and badly damaged another eleven within a thousand-yard radius of the zeropoint. Joint Task Force One, tallying the results, determined that 700 yards was a "serious if not fatal" damage zone, with serious damage at 900 yards, moderate damage at 1,000 yards, and slight damage at 1,500 yards. The majority of damage was caused by two factors--underwater shock, and the violent motion caused by it, as well as the impact with and violent motion from the blast-induced waves. [32] Five of the vessels not sunk within the 1000-yard radius were "immobilized." USS Pensacola suffered moderate hull dishing, damage to bulkheads, stanchions, and machinery foundations, holding down clips on turrets and battery mounts. USS Hughes was the closest destroyer to the zeropoint. It suffered major structural damage, including ruptured pipes and sea connections which flooded the ship, dished plating, and a badly damaged rudder and skeg. [33] A nearby ship had worse damage. USS Gasconade suffered a complete loss of longitudinal strength, the wrinkling of the bottom and shell plating, and partial flooding. The difference in damage was attributed to Hughes' broadside mooring and Gasconade's stern-to mooring. Gasconade rode the waves perpendicularly and hogged and sagged, while Hughes rode them parallel and consequently had its bottom and keel constantly supported by water. [34]

The transport Fallon was flooded to the waterline, with "severe structural damage to ship girders," buckled decks and plates, and a permanent "transverse-curvature twist in her hull." LST-133 had minor hull damage and cracked ballast tanks. Damaged but not immobilized were the destroyer Mayrant, with bulkhead, stanchion, and weather deck damage and minor flooding from ruptured pipes, the battleship New York, the transports Briscoe and Brule, the already wrecked submarine Skate, and LCT-816. [35]

SITE DESCRIPTIONS: VESSELS LOST DURING THE ABLE TEST

USS GILLIAM

USS Gilliam is the only Able test vessel dived and assessed. It is the most important Able vessel, given its accidental role as surface zero for the test.

Pre-Test Alterations

Documented pre-test alterations to Gilliam apparently were limited to addition of various exposure test instruments and military equipment. These included a bulldozer, searchlight and generator, fire-fighting equipment, radiation monitors, water-distilling equipment, and a VF aircraft secured to the aft upper deck.

|

| Wreckage of midships house, Gilliam. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Post-Blast Observations

Because the bomb detonated much closer to Gilliam than originally planned, the blast effects were greater than anticipated. Test instruments placed had been designed only for recording the expected pressures and failed to give good data. Hence the blast effects on Gilliam were difficult for the Navy to quantify.

Gilliam sank in 79 seconds, going down bow first at an estimated 70-degree angle according to the Navy's interpretation of post-blast photo sequences. [36] Navy divers assessing Gilliam's damage soon after the Able test found it nearly upright in 180 feet of water, with the stem, one bulkhead, and side shell-plating compressed a depth of six to ten feet and pushed to port: "the forward part of the ship is mashed down as though the blast acted like the hammer and the water an anvil." [37] The forward main deck was pushed down to within about five feet of the hull bottom, and starboard side shell-plating was stripped off as far back as frame 30--about 90 feet.

The flattened superstructure was pushed off the deck to port. According to Navy survey reports, "the weather deck from frame 60 forward was stripped of all deck machinery, deckhouse, hatch coamings, foremast, and other fittings. The sole fixed object noted on this deck was a port 40mm gun, with its round welded steel shield (gun tub) stripped off. The deck openings for hatches and trunks were plainly seen by the Navy divers." [38] The blast also opened up the chain locker, exposing the chain and tearing hawsepipes, with the chain still passing through them out of the hull. Portions of the vessel were blown overboard by the blast and littered the lagoon bottom. Navy divers noted bitts, which were retrieved for radiological testing, a 40mm gun, a blast gauge tower, and twisted shell plating lying on the lagoon bottom.

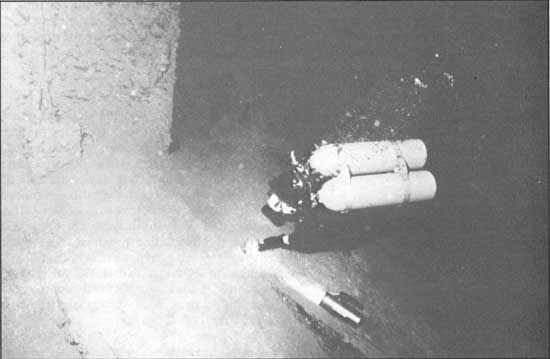

|

| Gas cylinders in No. 1 hold of Gilliam. (NPS, Video Freeze Frame) |

Navy divers recorded the wreckage with 60 underwater photographs. Unfortunately, we found these photographs to be mostly uninformative. Made from 4x5-inch negatives, the photographs show small areas or individual wreckage pieces, such as bitts and the twisted bulldozer blade. Poor visibility hampered the clarity of the photographs; it appears to have been less than six feet. The bulldozer, stowed on the weather deck, would be unrecognizable in the photograph without the label. The poor visibility probably resulted from blast-displaced sediment still suspended in the water column, indicating the photographs were taken shortly after the blast. Another indication of how soon the underwater photographs were made is that each is over-exposed, which may be a result of the high radiation levels noted in the Navy survey dive reports. The Navy divers also prepared a plan view and profile sketch of Gilliam's shattered hulk.

Site Description

One documentation dive was made on Gilliam. The full five-member NPS team swam over the deck, at 150 feet below the surface, from stern to bow. Water visibility was 50-100 feet vertically. The basically intact hulk of Gilliam was found to be upright on the bottom of the lagoon in 180 feet of water. Hull damage now appears to be more severe than 1946 diver reports indicated. It is possible that additional damage was inflicted on the submerged hull by the nearby Baker test detonation, and that what is seen, is cumulative damage.

The overall impression is that the hull has taken an enormous downward compressive force. The barely recognizable ship has the appearance of being smashed down into itself, with the successive deck levels pancaked down into the hold. These decks were originally supported by longitudinal bulkheads, stanchions, and rider frames of welded steel with 1-1/2-inch-thick steel gusset plates on lower hull beams. The hull sides above the waterline are bent inward, in some cases more than ten feet. The hull area below the waterline appears to have the least distortion.

It should be noted that Gilliam was not a lightly built vessel, even though not a combat ship. The Victory-type ships were built to correct some of the weaknesses observed in earlier Liberty ships. Gilliam was welded steel and very strongly built for heavy service. Gilliam's hull had transverse frames on 36-inch centers and a double bottom. There were numerous watertight compartments that were strongly built, contributing directly to hull girder strength.

The majority of damage, as the 1946 reports indicated, is forward. The bow appears crumpled and folded. A square frame, possibly a skylight, lies on the deck. The shell plating is peeled back and missing in places; the deckhouse stripped off and in part smashed down and to port. The impression upon viewing the hull is one of chaos--ship parts crumbled, torn, and scattered.

There were no deck fittings observed forward except a 20mm gun mount near remains of the aft bulkhead of the forecastlehead. This is the only bulkhead that seems to be in its original position. It is bent in an "s" shape that has a correspondingly distorted door in it.

Forward of the bulkhead is the 20mm gun mount. The remains of the forward hold, which contained railroad iron as test cargo and gas cylinders, is aft the bulkhead. Numerous gas cylinders and angle iron can be seen among the jumble of what was once the forward hold. The deck seems to have been ripped off, exposing the hold's contents. A kingpost lies off the starboard side. To port is the bulldozer, with its blade bent inward.

Within the jumbled wreckage, hatch coamings can be discerned as rectangular interruptions of ship scatter. The coamings appear to have been torn out of the deck. A perimeter of broken deck plate adheres to the hatch coaming margin.

Gilliam is the most damaged of the vessels the team examined in Bikini Lagoon. It is unforgettable.

USS CARLISLE

USS Carlisle was dived by the Navy ROV in August 1989. Videotapes of the ROV dive were assessed by us for comparison with Gilliam.

Pre-Test Alterations

Carlisle was loaded to 95 percent of its capacity with fuel and diesel oil. This ship was also loaded with 100 percent of its wartime allowance of ammunition "plus several loaded but plugged bombs, rocket heads and incendiary clusters throughout the ship. The Bureau of Aeronautics secured a VF airplane aft on the upper deck." [39]

Post-Blast Observations

Carlisle was moored close to and athwart Gilliam, the accidental zeropoint of the Able test detonation. Carlisle was 430 yards from surface zero. Carlisle's port side faced the blast. The blast displaced Carlisle approximately 150 feet, toppled the stacks and mainmast, displaced the superstructure to starboard, and damaged the foremast. The ship was first seen in photographs less than three minutes after the burst; "at that time she was smoking heavily amidships...she continued to burn and by burst plus 5 minutes 33 seconds she had assumed a 10 degree list to starboard." [40] The ship sank unobserved approximately one-half hour after detonation. In 1946 Navy divers located the wreck of Carlisle lying in 170 feet of water, "with a small list of about 5 degrees to port." [41]

Site Description

One ROV dive was made by Navy operators in 1989 on Carlisle, commencing on the port side near the bow and heading aft to the fantail, then running back along the port side to the hatch leading into the aft cargo hold. The ROV then headed across the deck, descended into the hold, and then came out, dropped to the starboard side, and ran aft along it for a short distance before ending the dive.

Comparing the identical, sister ships Gilliam and Carlisle offers a comparison of the Able bomb's damage to this type of vessel as observed at the different positions of 50 and 430 yards from surface zero. Gilliam was heavily mangled, as previously discussed. While Carlisle is more substantially intact, the ship suffered considerable and fatal damage at eight times the distance of its sistership, which the Navy attributed to Carlisle's beam-on orientation to the blast. Damage observed in the ROV dive would confirm this. The port shell plating is buckled, dented, and dished considerably, with a major failure forward. The superstructure, while more or less intact, has separated from the hull at the port side, and is pushed to starboard, as indicated in 1946 reports.

The most interesting damage to Carlisle is that done to the decks, which evidence the same compressive downward force of the blast that Gilliam's decks do, although not as severely. The port side of the deck around the aft hold's hatch has separated from the bulwark and the hull, and the deck seams have parted. The hatch coaming is bent and twisted, but remains attached to the deck plates except in its after portions, where it has pulled free. The deck has partially collapsed into the hold, and stanchions have buckled inside the hold, so that the subsequent deck levels are also deformed. A jumble of broken plate lies in the hold.

The after deckhouse is pushed down completely. A buckled bulkhead, with the turnbuckles for the wire rope rigging of the mainmast welded to it, is twisted down to the weather deck level. The formerly elevated port gun tub for a 40mm gun is now lying on the deck, without a weapon. Moving aft, bitts and fairleads remain attached to the deck, and two strands of anchor chain run from the fantail down into the silt on the lagoon bottom. These chains moored the ship's stern to a 10-ton mooring clump. Moving forward along the port side, a cargo boom from the mainmast slopes down from the deck to the lagoon floor. On the starboard side, the superstructure leans slightly over the starboard hull, which exhibits minor dishing. A gun mount on the aft port quarter of the superstructure is missing both its gun and the armored steel tub that surrounded it. Scattered artifacts, including a ship's running light and ammunition boxes, presumably from the gun tubs on the superstructure, lie off the starboard side on the bottom.

|

| Stern of Carlisle, showing smashed aft deckhouse and bitts. (U.S. Navy, ROV) |

SITE DESCRIPTIONS: VESSELS LOST DURING THE BAKER TEST

USS ARKANSAS

In addition to the Navy dives of 1946 and 1947, USS Arkansas was dived twice by the Navy ROV in 1989 and three times by the NPS team in 1989 and 1990.

Pre-Test Alterations

Arkansas' modifications for Operation Crossroads included blast gauge towers and test equipment installation. Also aboard was test ordnance. One photograph of Arkansas' deck shows a howitzer and a 90mm antiaircraft gun secured by turnbuckles and wooden chocks held by angle iron bolted to the teak deck.

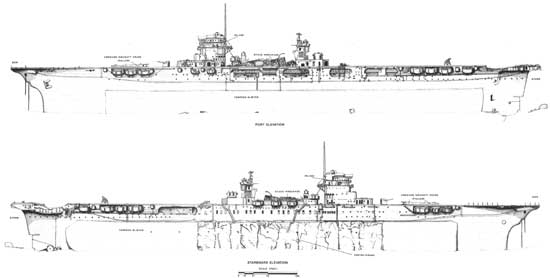

|

| Stern of Arkansas showing the two surviving port shafts with screws and the deformed stern plating. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Able Post-Blast Observations

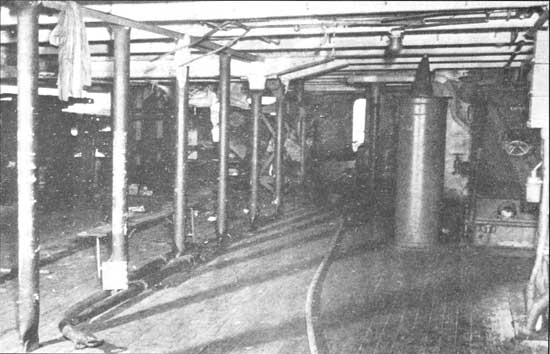

Arkansas was part of the Able test array, and was heavily damaged by the aerial burst. According to Operation Crossroads: The Official Pictorial Record, "although little damage was done to her hull and turrets, her wrecked superstructure showed the hammer-like effect of the bomb. Amidships she was a shambles." [42] Arkansas' damage was further described in Bombs at Bikini:

When the lagoon was first re-entered, she was still sending up clouds of smoke from smoldering fires on her decks. But the shock wave did the worst damage. Stacks, masts, and mast supporting structures suffered, as well as pipe rails, bulwarks, stowage spaces. Much dishing occurred. Many doors, stanchions, and bulkheads were badly damaged. [43]

If any alterations were made to the ship prior to the Baker test, they were not recorded in the documents reviewed.

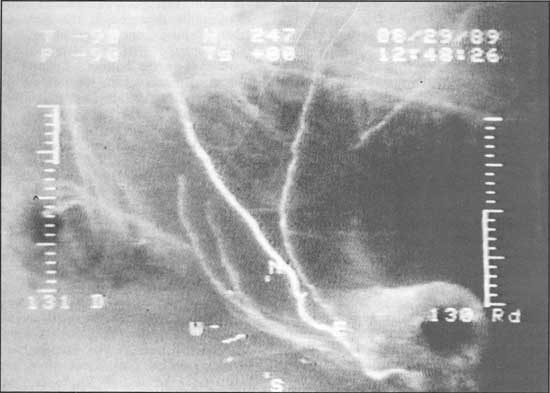

Baker Post-Blast Observations

In 1946, after Baker, Navy divers found the wreck "lying buried in the silt, bottom side up.... Most of the superstructure, including stacks, boat cranes and mast is not visible and is presumed to have been driven into the coral silt on the lagoon bottom." [44] They observed major hull damage:

Little is left of the shafting and the rudder has not been found. Only the port forward shaft without the screw has been found, and it is seriously out of line. No struts have been sighted and two large holes aft indicate the after two shafts have been completely torn out, stern tubes and all, leaving the surrounding area badly distorted and broken. [45]

The hull's shell plating either dished in (in some cases as much as six feet), tore, bent, or dented around the frames, parting butts and plate seams. In some cases the transverse framing failed. The torpedo blisters dented, bulged, and separated from the hull in several areas. Rivets failed throughout the hull, and near the No. 2 turret, a 15-to-20-foot wide dent of undetermined depth ran from the bottom up to the turn of the starboard side bilge.

The Navy determined that the upsurging blast water "acted on Arkansas from below and to starboard at a point approximately one-third of her length from the bow." [46] This mass of upsurging water capsized the ship to port. The Navy concluded, "The many holes and rivets seams which were opened throughout the entire length of the shell plating by the underwater explosion were the probable sources of flooding. A water wave which smashed over the Arkansas...may have partially aided in swamping the ship." [47]

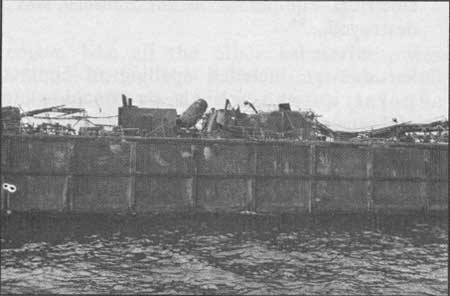

|

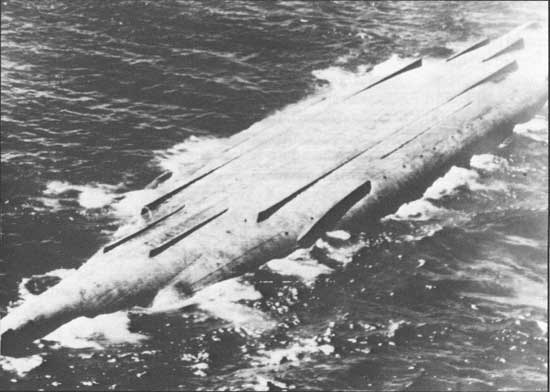

| This 1948 photo of the capsized battleship New York's intact bottom offers a stark contrast to the mangled Arkansas. (U.S. Naval Institute) |

Site Description

The 1989 and 1990 surveys found that the seriously damaged Arkansas lies inverted on the bottom of Bikini Lagoon in 180 feet of water roughly aligned east-west, bow to the east. The battleship was aligned close to this position for the test. The former weather deck level is located at approximately 160 feet below the water surface; the port casemate, or aircastle, is located at 170 feet, while the deformed keel is at the 100 to 120-foot level.

Arkansas has a slight list to starboard. The port side is more or less intact, while the starboard side is crushed and flattens out onto the lagoon bottom. The forward hull area is heavily damaged; the bow structure twists and is bent down and to starboard.

|

| Perspective sketch of Arkansas. (NPS, Jerry Livingston and Larry Nordby) (click on image for a PDF version) |

The hull bottom is markedly dented and rippled along the series of longitudinal supports, creating a series of "steps" that gradually slope down from the port bilge keels, past the deformed keel to the smashed starboard side, where frames splay out from the shell plating on the lagoon bottom. The shell plating has parted in some areas. Some pieces of wreckage containing frames, identifiable by their lightening holes, lie off the side.

In the stern, the propeller shafts have been torn away. The forward port shaft, with its three-bladed screw, is intact but deformed and bent outward. The shaft struts are missing. The after port shaft is bent to port. There is no trace of the starboard shafts or screws; it is possible that the entire 142-foot shaft lengths were torn free of the hull. The rudder and stern are missing. Broken hull fragments lie off the starboard side.

At the bow, the only identifiable features are the bulbous stem, which normally protrudes forward below the waterline, a chock on the port bow, and the two hawsepipes for Arkansas' two port anchors. This battleship carried three anchors, two to port and one to starboard. Two anchor chains extend from the forward hawses into the sand. The hull is cracked just below the gunwale forward of the No. 1 turret.

The chains, which are still attached to the deck by stoppers, hang down below the inverted deck. The ship is raised on the port side, allowing access to the deck. The vessel appears to be supported on the forward turret, the two 12-inch gun barrels of which can be seen pointing forward and slightly to port.

The ship's superstructure was not observed by Navy divers in 1946 because of a heavy silt layer that lay over and around the wreck. This silt layer, created by the blast, has now been scoured away, exposing the hard coral and sand of the lagoon floor. The lagoon bottom is less than six feet below the weather deck in most locations observed forward. This spacing accommodates the turrets and a smashed superstructure reported in the Able post-blast assessment.

|

| Daniel Lenihan swims forward past the bilge keel of Arkansas. Longitudinal failure of the shell plating resulted in the long dents in the hull. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

The 1946 Navy reports suggest the ship was smashed nearly straight down into the lagoon floor. This observation is supported by the ship's nearly level position on the bottom, with only a slight starboard list. The flattened hull bottom and the superstructure being directly beneath the hull also reflect a straight down pressure on the hull. Superstructure elements would be expected to be visible on one side or the other if the vessel had rolled. Apparently, the hull was capsized by the uplifting water and smashed straight downward by the millions of tons of collapsing water column.

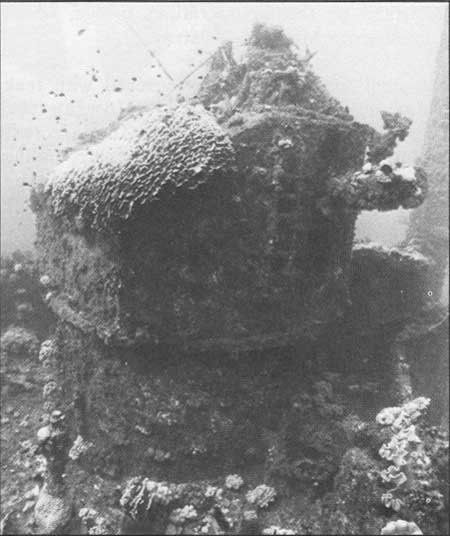

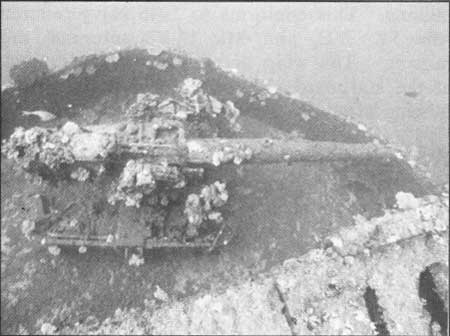

The portside casemates, known as "air castles," built of 6-inch-thick steel armor plate, are intact. Three 5-inch/51 caliber Mk13 guns on single mounts are visible. These 11-1/2-ton, 22-foot-long weapons were manually operated, fired a 50-lb. projectile with an eight-milerange at a 20 degree elevation. The guns are slightly elevated and have swung to port.

|

| Port aircastle of the capsized Arkansas. The barrel of a single 5-inch/51 caliber gun protrudes. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Most of the gunport shutters are missing. Reportedly damaged in the Able test, these shutters have fallen away, probably when the ship capsized. At least two lie beneath the port side on the bottom. Splinter shields for 40mm antiaircraft guns were noted beneath the inverted aircastle; the weapons themselves were removed before the test.

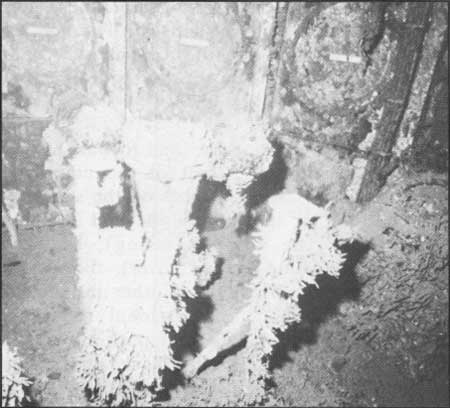

Inside the casemate, two 5-inch rounds remain in the ready rack. The guns still have rangefinders and sights. In the casemate messing and berthing spaces, stanchions, which once provided support for the gun crew hammocks, remain in place but slightly bent from compressive forces. Remarkably, the glass cover and bulb for a battle light was located undamaged on the inverted ceiling. Overhead, the teak deck is missing, presumably consumed by marine organisms, leaving only metal deck fasteners attached to the steel underdeck. A wire-cable reel for the port paravane is stowed at the aft end of the compartment. An ammunition hoist hangs open from the deck.

|

| Two ROV views, taken at slightly different angles, of the barrels of the 14-inch guns of Arkansas' No. 1 turret. (U.S. Navy, ROV) |

|

| Inside Arkansas' port aircastle, Dan Lenihan inspects an unbroken light inside its wire and glass safety cage. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

|

| Looking forward in the port aircastle of Arkansas, at Bikini in 1946. The light that Lenihan investigated in 1990 is visible in the upper right corner of the photograph. (National Archives) |

This 21-foot-wide compartment was entered through a seven-foot wide longitudinal passageway that runs from port to starboard. The passageway leading to the starboard air castle was not entered. The port air castle included the entrance to the admiral's cabin; Arkansas was fitted as a flagship. This cabin was not entered. There was also a 32-foot-wide space between each passageway that contained boiler uptakes, evaporators, and the ship's enlisted cafeteria with steam tables opening into each passageway. These passageways were not entered.

USS SARATOGA

USS Saratoga was the principal focus of assessment and documentation during the Bikini field seasons. The vessel is one of the most accessible to divers, and consequently of primary interest for evaluation as a dive site.

Pre-Test Alterations

Saratoga was modified for Operation Crossroads. Nearly two-thirds of the ship's armament was stripped, including two of the houses with the twin 5-inch guns. Other fixtures, including compasses and the ship's bell (now at the Washington Navy Yard), were removed. To measure the effects of the bombs, aircraft, vehicles, and radar were placed on Saratoga. Blast gauge towers and other instruments were mounted at desired locations.

Loaded with 700 gallons of fuel oil, 15 tons of diesel, and 66-2/3 percent of its ammunition, Saratoga was sent to the bottom in a near-combat-ready state. [48]

|

| Saratoga, hit by the first blast-generated wave, rises 43 feet and lists to port, 10 seconds after detonation, in this view from Enyu Island. (U.S. Naval Institute) |

Baker Post-Blast Observations

After the Baker detonation, the ship was blown to a position 800 yards out from its original position before drifting back in and sinking 600 yards from the detonation point. The detonation of the Baker test device on July 25 created a blast wave crest that lifted Saratoga out of the water. Eleven seconds after detonation, the 94-foot-tall wave crest was 330 yards from the detonation point; at 23 seconds, it was 660 yards off and 47 feet tall, diminishing to 24 feet tall at 1,330 yards at 48 seconds after detonation. Official reports state that Saratoga's stern rose 43 feet and the bow at least 29 feet. A large wave of water washed over the ship, sweeping away five TBM-3E and SBF-4E aircraft stowed on deck, as well as vehicles and equipment placed there for the test. According to test data analysis, "it appears highly probable that shortly after the rise on the first wave crest, the Saratoga fell into the succeeding trough and was bodily hit by the second wave crest...." [49]

|

| Saratoga's island, stack, and No. 1, 5-inch mount after stripping the ship for Crossroads. This photograph was taken at Naval Air Station, Alameda, California, February 27, 1946. (Floating Drydock) |

In 1946, Navy divers made limited dives on the wreck and reported that the forward starboard strut in the stern had torn free, buckling shell plating and tearing out the doubler plates. The flight deck at the stern was dished in to a maximum depth of 12 feet that splintered the wood deck but did not penetrate the steel deck beneath. The funnel had collapsed to the flight deck, with three-quarters lying on the deck and the remaining quarter "erect but...twisted about 20 degrees counterclockwise." The top foremast was broken off above the SK radar platform. The starboard side of the hull exhibited a three-to-six-inch dishing in the central area of the ship. [50]

When Navy divers inspected the wreck, they reported it lying in 180 feet of water on the port bilge at a 10- to 15-degree angle. The bow reportedly tilted up at an approximate five-degree angle. The ship had settled into the bottom, to the shaft level, leaving the screws exposed. The starboard bilge was about seven to eight feet above the bottom. The Navy determined from oil leaks that the bottom shell plating had ruptured. This, they concluded, along with a tear in the hull near the starboard quarter, and the failure of sea chests and valves, had sunk Saratoga. [51]

|

| The same view today. The stack, mast, and radar antennae are conspicuous in their absence. (National Geographic Society, Bill Curtsinger) |

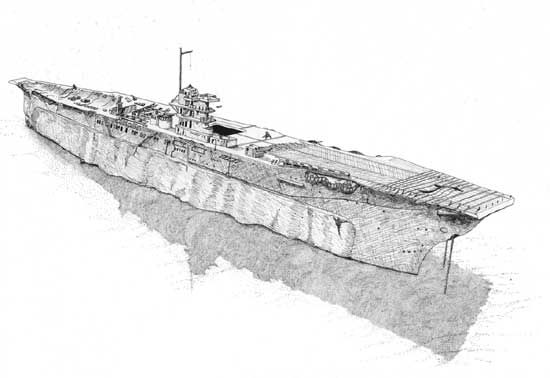

Site Description

In 1989 and 1990 dive surveys found that the virtually intact USS Saratoga still lies upright on the bottom of Bikini Lagoon in approximately 180 feet of water. The vessel rises to within 40 feet of the surface, with the island and mast visible from the surface. Numerous hatches and the elevator bay stand open. The vessel strongly retains its integrity as a ship and is easily identifiable as Saratoga. Although the carrier's entire exterior was surveyed, emphasis was upon the starboard side (which faced the blast) and the flight deck. Few interior spaces were examined other than the hangar deck amidships, as well as the island, the flag plot, navigation bridge, and aerological office. Additionally the auxiliary radio room and windlass area was entered through a hole in the flight deck.

Saratoga readily evidences the effects of the Baker test bomb's detonation. More precisely, the ship shows the aftermath of a nearby nuclear detonation's pressure wave, the effects of being lifted 29 to 43 feet, being hit by enormous waves, and the results of tons of water thrown up by the blast falling on the decks. Below the flight deck level, damage primarily consists of dishing along the starboard hull shell plating, most noticeably on the torpedo blister, which is pushed inward between frames to a depth of six feet in some areas. Shell plate dishing increases toward the stern. Some hull cracks show; it is not known whether they resulted from bomb damage or post-depositional settling.

The worst hull damage is starboard side aft. Here, shell plating and doubler plates above the turn of the bilge and the torpedo blister are torn free, exposing frames. Navy reports in 1946 and 1947 indicated that all shafts and screws were visible, with the starboard struts broken. This was also noted in the 1989 survey, with the forward starboard strut broken violently enough to damage the shell plating around it.

Flight Deck. The flight deck shows extensive damage. A combination of blast wave and thousands of tons of water falling from the blast column collapsed and compressed the aft flight deck, beginning close to the stern and continuing forward nearly to the funnel about 200 feet down to a distance of 12 to 20 feet between the outermost longitudinal bulkheads. These bulkheads, which provide the main flight deck support, are 70 feet apart.

Navy reports in 1946 noted "the indentation [of the flight deck] is gradual with no abrupt breaks or bends. There is no indication that the steel deck has ruptured but the wood decking has been splintered and broken... [52] The steel deck is now ruptured. It could have been ruptured in 1946, with splintered wood obscuring the break to observers. A large break about 100 feet aft of the stack is clearly visible and another open deck crack can be seen on the starboard side near the boat bay.

The major flight deck failure is near the funnel. A partial deck break beneath the collapsed funnel is probably attributable to the latter crashing down on it. A roughly square depression aft roughly conforms to the No. 2 elevator position, which was sealed off in early 1945 during Saratoga's last pre-Crossroads refit. The platform that covered the elevator was reported missing in 1946: "This platform was reported found on the starboard quarter of the ship." [53] During our dives we observed the platform had collapsed into the hangar deck. What the 1946 Navy divers thought was the platform on the starboard quarter is probably the fantail drip pan, which is still in place. This drip pan was under one of two SBF-4E Helldivers mounted on the fantail for the test. The starboard aircraft, BuAer serial number 31859, was secured to the pan with its wings spread; according to the BuAer final report for the plane, it was "blown over the side from the Saratoga before the ship sank. The steel drip pan in which the airplane was secured was left on deck and sank with the Saratoga." [54] A brief unsuccessful search was made for this plane.

|

| Saratoga's flight deck, its wood decking now gone, is marked by steel battens, fasteners, and stanchions. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Saratoga's main flight elevator, forward the funnel, lies at the bottom of the shaft, diagonally bent nearly 90 degrees. The elevator was stowed in the "locked up" position for the test, as it had been for Able. In that test, it had dished down "slightly," with "a number of broken welds, in a number of places below the platform, on the structural members." [55] The Baker blast compounded this damage; 1946 aerial photographic analysis and diver's reports showed

the platform was dished in considerably in the center and slightly to port, to a depth of...four to six feet probably from the effect of falling water and blast effect....The port side of the elevator had been depressed downward about three feet and the whole platform tilted to starboard, so that the starboard side of the platform extended above the flight deck level about one foot. [56]

The elevator platform's location at the bottom of the shaft in its current position is attributed to post-depositional settling.

|

| The secondary conning position on the forward edge of Saratoga's collapsed stack. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Near the bow, the flight deck is partially collapsed. This collapse generally conforms to an area damaged by kamikaze attack off Iwo Jima on February 21, 1945, and subsequently repaired for quick return to service. Diver reports in 1946 noted that "the flight deck forward appeared to be intact" and that "the flight deck in the area of the catapults was undamaged by the blast." [57] The deck collapse in this area may also be postdepositional and attributable to a twice-damaged area weakening with corrosion and finally collapsing after the sinking.

Superstructure. Above the flight deck level, the most apparent damage is to the ship's funnel. The funnel split at the 04 level and fell to port across the flight deck, slightly angling toward the bow, indicating a lateral twisting probably from the angle of the 90-foot wave that hit it. The blast wave or the water column's falling mass likely contributed to the present distortions. The funnel completely tore free at the base, exposing the intakes. In 1946, the funnel after-quarter remained standing. Post-sinking funnel collapse has left only a fifth of the original funnel standing.

The funnel has completely collapsed into itself, with only the major longitudinal and transverse framing left intact. The plating lies broken and scattered inside the frames on the deck. Blast and wave effects have bent the funnel's horizontal framing to port, in some cases more than six feet. The forward end of the toppled funnel is intact. The secondary conning position and the broken SM fighter-director radar mounted atop the funnel's forward end are recognizable. Diver reports in 1946 noted that this "radar equipment...on the forward portion of the stack was damaged." [58]

Damage to Saratoga's island and mast includes shattered deadlights, hatches and doors blown off their hinges, toppled Pelorus stands, and sheared antennae. The single-pole mast aft the island was blown off at its crosstree; the wire rope that rigged the mast lies festooned on the after area of the island. The SK radar antenna atop the mast fell forward; pieces of the antenna lie tangled and broken on the island in front of the flag plot bridge. The mount for a whip antenna lies on the deck outside the navigation bridge. One level below, a searchlight that once stood on the platform aft of the mast lies face down on the deck. The stub mast that projected aft the pole mast is now bent 90 degrees to port and broken. A spar from the mast lies on the flight deck outboard the funnel; a cable runs from it over the starboard side. From this cable a whip antenna mount is suspended. Other antenna, such the Mark 12-22 array atop the MK 37 director on the air operations bridge, as well as all other observed director locations, are missing. This conforms to 1946 Navy reports: "the SK, YE, and Mk 12-22 antennae are missing. The whip antenna installed forward, at the starboard side of the flight deck, were missing after the blast." [59]

|

| Perspective painting of Saratoga. (Tom Freeman) (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Perspective drawing of Saratoga. (NPS, Jerry Livingston and Larry Nordby) (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Profile views of Saratoga. (NPS, Larry Nordby and Jerry Livingston) (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Plan view of Saratoga. (NPS, Larry Nordby and Jerry Livinston) (click on image for a PDF version) |

The various starboard hatches are mostly blown in, partially collapsed, or altogether missing. All porthole deadlight blast covers are closed; the glass in every porthole observed was missing. Wire-rope life nets, once strung above the sponson deck, are missing with the exception of some loose netting hanging forward of the starboard boat bay and near the stern.

Armament. Saratoga's primary armament was the 81 to 83 aircraft aboard. When subjected to the Baker test blast, Saratoga had five aircraft secured to the flight deck; all were swept off the ship by the blast or waves. In 1988 Holmes and Narver and U.S. Navy divers reported an airplane on the bottom off the starboard hull. This aircraft was not observed in 1989. The four aircraft stowed for the Baker test--three "Helldiver" Navy single-engine dive-bombers and an Avenger single-engine torpedo bomber--were observed in the hangar. A more detailed discussion of these planes will be found in the section detailing Saratoga's interior.

|

| Mark 37 director at the air defense level of Saratoga's island. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

|

| No. 1, 5-inch/38 caliber mount on Saratoga. The island is faintly visible in the background. (National Geographic Society, Bill Curtsinger) |

Saratoga also carried eight paired 5-inch/38 caliber guns in four houses--two forward, two aft. Before Crossroads, during the ship's 1946 stripping at Hunter's Point, two of the houses were removed: the No. 2 gun position forward the island (though its barbette remains atop the handling room) and the No. 4 gun position abaft the funnel. The remaining two guns in the No. 1 position are elevated 20 degrees and trained forward, whereas the two guns in the No. 3 position are level and pointed to starboard.

|

| Gun tub, with quad 40mm mount, aft of Saratoga's island. Abaft the 40mm mount is a Mark 51 gun director; further aft is stack wreckage. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Other weapons were also removed for the tests, but a representative sample was left to assess the blast effect. For Baker Saratoga carried in addition to the paired guns, 12 single 5-inch/38 caliber guns; four were noted in the 1989-1990 dives. Six of the original twenty-four quad Bofors antiaircraft 40mm guns were also located. The carrier also mounted 52 Oerlikon antiaircraft 20mm guns on the sponson deck; five of these were located, two lying on the lagoon bottom aft close to the sheared off stern sponson gun platform on which they were mounted. The sponsons were torn off either by huge bomb-generated waves or falling water from the collapsing column. Twelve sponson-mounted Mk 51 gun fire-control directors were noted next to the antiaircraft guns.

Saratoga carried 66-2/3 percent of its normal ammunition complement for the tests. Presumably live five-inch/38 caliber shells were actually found inside the 5-inch gun turrets. Aerial bombs and torpedoes were found in the hangar and will be discussed later.

|

| Single 5-inch/30 caliber AA gun on Saratoga's starboard bow gallery or sponson. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Various fire-control radars were also noted; the only types specifically identified were the SK and SM, as well as the Mark 37 director atop the island on the air-operations bridge, which is missing its Mark 12-22 array.

The steel flight deck, once covered with teak decking, is now exposed, allowing the observation of battens used for aircraft tie-downs, with small wood pieces surrounding the iron deck pieces. The area of the palisades is discernible, as are the tracks for Saratoga's Mk II hydraulic catapults forward. Aft, 21-inch bitts and other arresting gear, with wire rope attached and running athwartship, are still in place. Other extant deck furniture includes the forward aircraft crane, which has dropped and lies on the deck. The crane was noted in 1946 reports as not appearing "to be damaged by the blast." [60] It was, however, lying on the deck when observed by Navy Divers in 1947. The collapse of the crane may be depositional. The airplane jettisoning ramp, which lies portside abeam the island, and various valves and fittings as well as fueling booms lie to starboard outboard the funnel. Both the bomb and torpedo elevators were seen. The bomb elevator hatch is open; the torpedo elevator is secured.

|

| Live 5-inch/38 caliber cartridges, without warheads, in aluminum cartridge cases in Saratoga's handling room for the No. 3, 5-inch mount. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Ground tackle aboard includes an anchor stowed in a port bow hawsepipe and an anchor chain that runs from the bow to the seabed. The chains run into the sand but are no longer attached to a mooring. Saratoga was moored by 10-ton "clumps" made of anchors and concrete; one of these clumps is off the starboard side of the ship. Others were separated by the blast effect, which lifted the carrier and displaced it several hundred yards. A Navy stockless anchor, attached with wire cable to a bitt, lies on the flight deck aft the funnel to starboard. It may have been a mooring that was displaced by the blast and dumped on the ship by the falling water column; it lies in the indentation of the flight deck.

|

| Five-inch cartridge case, showing the cartridge. The warhead was added by the gun crew in the handling room. (NPS, Candace Clifford) |

Test Equipment. As part of the tests, military teams and scientists placed recording equipment and gauges aboard Saratoga. Much of this equipment remains, in some cases as traces of badly damaged instruments or mounts. Mounting brackets and pallets for military field equipment lie aft the funnel; on one of these pallets, on the port side flight deck near the after elevator, around frame 120, stands the remains of Army Signal Corps test equipment. On the pallet are the remains of the packing case and "safety trough" for an SCR-399 radio set and an air-cooled diesel power unit that were mounted to the deck "by means of ring pads, 1/2-inch wire cables and turnbuckles just inboard of the port rail...at frame 120." [61] Another power unit, M7A1, with a trailer-mounted SCR-584-B radar set, was placed aft of this set-up on the flight deck weather edge "approximately 50 feet aft of the main stacks and superstructure." [62] Nearby was a "shock-mounted" trailered PE-237 power unit. [63] Perhaps these are the source for some of the observed wreckage; a portion of a trailer, with rubber tires, lies in the indented area of the flight deck in this area. Another trailer lies on the seabed off the port side.

The most obvious piece of test equipment is an Army long antiaircraft gun bolted to the deck on the port side abaft the funnel. It is reported that the Army Ordnance Task Unit 1.4.3 placed six items on the carrier for Baker: 1) a light tank, 2) a heavy tank, 3) an M1 cable system, 4) a 90mm GMC, Mark 36, 5) a 155mm Mark 2 gun, and 6) a 90mm Mark 2 antiaircraft gun. The weapon on the deck is probably the 155mm. [64]

|

| Divers illuminate the bow and mooring cables of Saratoga. (National Geographic Society, Bill Curtsinger) |

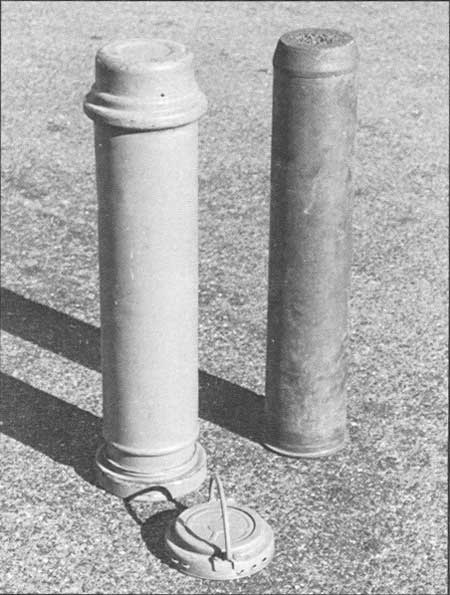

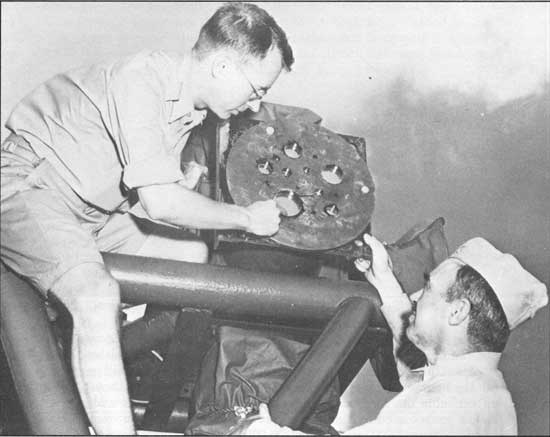

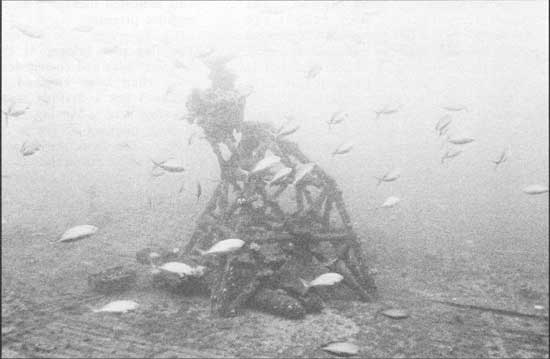

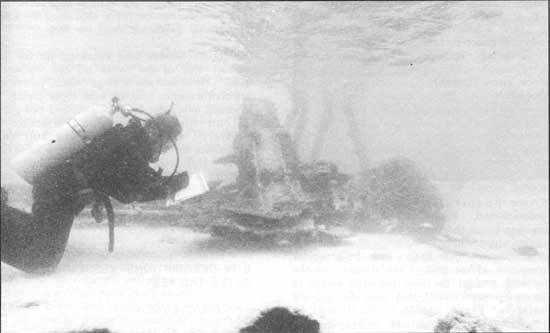

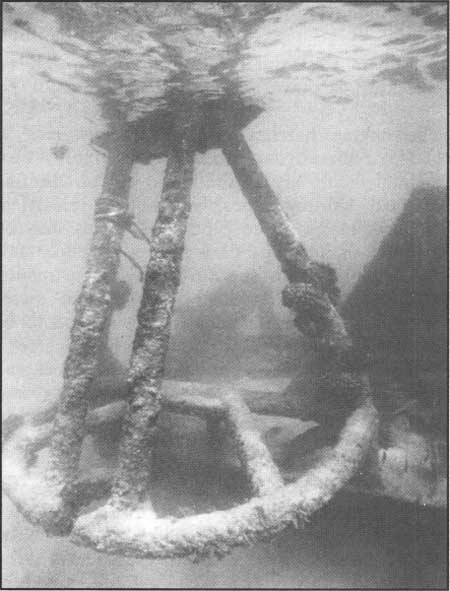

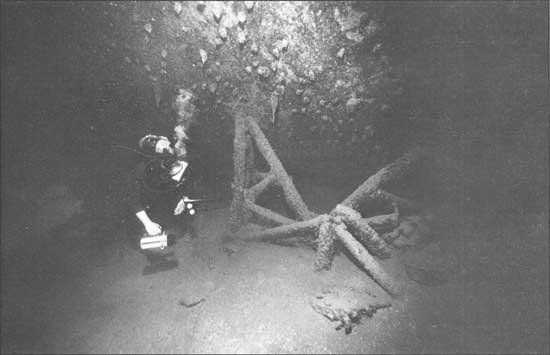

Also on deck are two blast gauge towers, one forward and one aft. The forward tower lies off the port forward corner of the elevator; the after tower is set about 50 feet abaft the funnel. These roughly pyramidical towers were known as "Christmas trees" and served as mounts for peak-pressure measurement gauges. To mount the gauges in proper position, test accounts state "typically, they [the gauges] were bolted to 'Christmas trees,' sturdy 9-foot-high structures of heavy steel pipes. The Christmas trees were ordinarily welded to the upper decks of the target vessels." [65] The pressure gauges were made of 1/4-inch-thick brass plates with round holes of various diameters up to two inches bored through them. Tin foil was sandwiched between two plates, which were then enclosed at the rear by a "sturdy air-tight cover, to prevent instantaneous equalization of pressure." [66] Blast effect in the range of 0 to 50 psi was measured by foil rupture; a greater blast effect ruptured smaller diameter foil, while a lesser blast only ruptured the more exposed foil in the larger diameter holes.

Another instrument mount type was observed on the flight deck aft. Welded to the deck on the centerline, but arranged in a nearly square pattern are three plate-steel boxes, each with a differently shaped bracket atop it. These are probably mounts and housings for delicate gauges and recording devices. The primary requirement for most instruments used in the Operation Crossroads tests was that they be

really rugged. Despite the need for using ingenious recording systems, the gauges and their mounts must survive the terrific overpressure. It is pointless to use a precision gauge which is promptly flattened or blown overboard. Hence delicacy was not a characteristic of the instrument cases taken to Bikini; on the contrary, many of the designers encased their instruments' delicate works in cases built of 2-inch-thick steel which could withstand the pressure. [67]

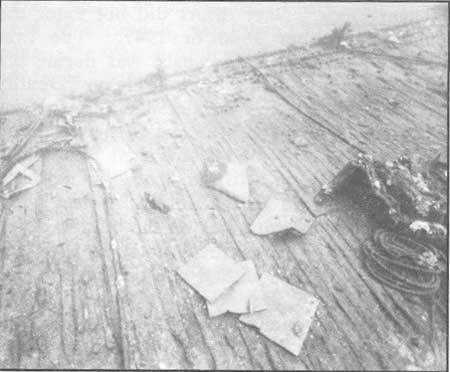

A large number of 1-inch-thick lead plates, some with large square holes cut in their middles, were observed lying atop the No. 3 gun house, and on the flight deck near the radio set pallets and inboard the 155mm gun. Nearly all lay bent or crumpled. These lead plates are probably the remains of indentation peak-pressure gauges used to measure pressure in the range of 20 to 1,000 psi or 100 to 6,000 psi, depending on the thickness of the lead. [68] One report notes "pressure is recorded in terms of indentation produced by a small steel ball forced against a sheet of lead. The greater the pressure, the deeper the indentation." [69] The last type of test equipment seen on the ship were two parabolic chromed, polished metal dishes. A 12-inch dish lies in a rubble pile at the after starboard corner of the deck outside the navigation bridge chartroom. A 24-inch dish lies in a rubble pile at the after port corner of the same deck. These are the remains of a "pendulum type inclinometer" developed by the material laboratory of the New York Naval Shipyard for the tests. The inclinometers were used to automatically record angles of rolls and pitch of target ships. Mounted on steel plate with a weighted arm designed to remain vertical at all times, the discs were scratched by the arm which left its record on the "shiny discs provided." [70]

|

| Army 155mm antiaircraft gun on Saratoga's flight deck, portside amidships. (NPS, Daniel J. Lenihan) |

Island. Because of the time limitations caused by the depth of the dives and the need to focus effort on documenting the ship's exterior, only a few compartments were entered. Most were on the island. The compartments entered on the island were the flag plot, navigation bridge pilothouse, and the aerological office. All hatches and doors that enter the flag plot stand open--most blown off their hinges--with the exception of a closed hatch on the after starboard corner. Navy divers noted in 1947, that most of the hatches were distorted or blown down. Some inward and others outward. This indicated damage from both positive and negative pressure.

The flag plot bridge, at the forward end, contains radar and communications equipment; on a chart table attached to the starboard bulkhead lies a drafting machine, missing its drawing arm. Moving aft, bulkheads are missing, allowing access to the admiral's day cabin. The bunk, head, and a small white porcelain sink are in the cabin, which is largely open to the sea because the exterior bulkhead is missing in several areas. A hatch leads out to the starboard side of the flag plot bridge; on the deck outside, a ladder, with traces of lashings on the handrail, leads below to the navigation bridge. Forward the ladder and matched by another to port is a Pelorus.

The navigation bridge portholes are missing their deadlights. External blast covers with viewing slits cover all portholes with the exception of the last porthole aft on the starboard side. That blast cover hangs down on its hinge. Outside the bridge are the mounts for two Pelorus; lying on the deck on the starboard side are a battle light, an air-raid siren, and an inclinometer gauge. A non-watertight interior door, probably from the hatch leading into the pilothouse, lies on the deck. Badly corroded, it retains a rubber gasket. Aft of it lies the watertight hatch for the chartroom. The watertight pilothouse door is open and hangs on its hinges. Through this hatch is an open companionway. The corresponding hatch on the port side is closed and dogged.

|

| Installing a ruptured foil peak pressure gauge on a "Christmas Tree," in 1946. (U.S. Naval Institute) |

|

| Aft "Christmas Tree" blast-gauge tower on Saratoga. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

|

| Lead indentation pressure gauges on Saratoga's flight deck, port side, amidships. (NPS, Daniel Lenihan) |

|

| Catherine Courtney inspects the blast covers on Saratoga's bridge. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

An open door to the right (and forward) opens into the pilothouse. Most of the equipment remains inside. A chart table on the starboard bulkhead is first encountered; beyond it sits the helm (with the wheel missing), binnacle (missing the compass and cover), the mounts for the signal telegraph and other instruments now missing, and a navigational radar set. Moving to port, a panel with push switches is labelled with an engraved black plastic sign that provides "emergency signals." On the bulkhead above it is an annunciator. Moving aft on the port side, an indicator is next encountered. This instrument, with a digital display, is marked "ENGINE TELEGRAPH," and "REVOLUTIONS AHEAD." On the aft bulkhead is an open door, with the door partially collapsed into the companionway. Moving to starboard is a chart table and the electrical panel for the ship's lights. Several black plastic engraved labels are fixed to the bulkhead next to switches; among them are "MAN OVERBOARD," and "MAST HEAD."

|

| Helm position on Saratoga's bridge, showing the binnacle, helm, and radar. The compass, wheel, and other equipment has been removed, presumably for Crossroads. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

To starboard of this panel is the doorway through which entry into the pilothouse was made. The overhead is covered with a thin film of oil.

The chartroom is aft the bridge. The only access is by a starboard bulkhead hatch; it is blocked by a partially fallen piece of electrical equipment, possibly a SC-3 radar set. A nitrogen bottle for an SC-3 radar is mounted on the after starboard external corner of the chartroom. The chartroom was ventilated on the port side by a circular vent--once protected by a hinged cover; the remains of the cover hang down by the hinge.

The aerological office is the aftermost compartment in the aerological platform, which is one level above the flight deck on the island. The starboard bulkhead has fallen away, providing access into the office. The original access, a door on the port bulkhead, stands open, with the hatch off its hinges. The interior of the office is largely open; against the port bulkhead is a steel desk bolted to the deck; forward is an unidentified piece of electronic equipment and a steel file cabinet. Beyond this is a companionway that leads to a ladder that provides access to the decks above and below.

Hangar Deck. Navy divers did not enter the hangar in either 1946 or 1947. The first recorded entry into this space was during the 1973 filming of the documentary, "Deadly Fathoms," for which no detailed observations were made, save the presence of one or more aircraft. The 44-by-44-foot shaft drops one deck into the hangar deck, which is approximately 20 feet high and 70 feet wide. The elevator platform lies on the bottom of the shaft. Navy divers correctly noted in 1946 that the platform "was dished diagonally from the forward port to after starboard corner." [71] The elevator shaft opens aft into the hangar deck. Just inside the deck, near the after starboard corner, lies a rack of what the Bureau of Ordnance's records show are five 500-lb. general purpose aerial bombs, model AN Mk 64, Mod 1, equipped with AN Mk 243 nose fuzes and AN Mk 230 tail fuzes--the primary armament of the SBF-4E Helldiver aircraft in the hangar. These weapons remain in their test location at frame 82 on the starboard side of the hangar deck. Inside the deck, at the after port corner of the elevator, are four 350-lb. aerial depth bombs, model AN Mk 64, Mod 1, "plaster loaded and fuzed" [72] equipped with AN Mk 219-3 nose fuzes and AN Mk 230-6 hydrostatic tail fuzes. Navy EOD divers working with the NPS team confirmed these identifications. One of these fuzes was armed and was defuzed by a Navy EOD technician who "safed" it with epoxy. These bombs are in their original test location at frames 80-81 on the port side of the hangar deck. [73]

Inside the hangar deck, moving aft, are two loose fueling drums and loose bomb and torpedo racks once secured to the bulkheads and overhead. Pipes for fire sprinklers hang from the overhead, some loose. Electric lightbulbs are intact and line the overhead, which is covered with a thin film of fuel oil released from the ship's bunkers. Three U.S. Navy dive-bombers, Curtiss SBF-4E "Helldiver" single engine aircraft, were observed during the dive, stowed with their wings folded. It was found that the forward airplane's engine, cowling, and propeller have detached from the plane and lie on the deck. This aircraft, which should be BuAer serial number 31894 according to the Bureau of Aeronation Report, was according to the report, stowed on the hangar deck at frame 90, starboard, for the Baker test. The plane, armed with twin 20mm fixed M-2 cannon, with twin .30 caliber free guns aft, was noted as being "intact and operable, wings folded" and combat-ready except for "bombs, ammunition, fuel, safety equipment, pyrotechnics." The bolts were removed from the guns, which were loaded with ten rounds. The clock was removed from the instrument panel for the tests. Aft of plane 31894, a second SBF-4E, BuAer serial number 31850, was observed, noted in the Bureau Report as stowed on the hangar deck, frame 100, starboard, in the same condition and configuration as 31894. [74] Aft of plane 31850, a third, partially crushed SBF-4E, BuAer serial number 31840 was found. The Bureau Report noted this plane as stowed on the hangar deck, frame 110, starboard in the same condition and configuration as planes 31894 and 31850.

|

| A 500-lb. bomb on USS Yorktown. (NPS, James P. Delgado) |

|

| Five general purpose 500-lb. bombs, AN-Mk 64, on their bomb carts, on the starboard side of Saratoga's hangar deck at frame 82. Lying forward of the bombs is a single 350-lb. depth bomb, AN-Mk 64, originally stowed with four others on the port side, which rolled free and lodged against the 500-lb. bombs. (National Geographic Society, Bill Curtsinger) |

All three aircraft were aboard Saratoga for the Able test; 31894 was on the hangar deck, frame 110, port side; 31850 was on the hangar deck, frame 100, starboard; and 31840 was on the hangar deck, frame 110, starboard. All three aircraft, as well as SBF-4E, BuAer serial number 31889 (also on the hangar deck, frame 100, port) were undamaged. Plane 31889 was removed from Saratoga and placed aboard USS Independence, and 31894 was shifted to starboard forward of 31850 and 31840, which remained in their Able test locations, for the Baker test. All aircraft were noted as "missing--Sank with Saratoga," after the test. A fourth aircraft, a TBM-3E "Avenger" torpedo-bomber, BuAer serial number 69095, noted as stowed on the hangar deck, frame 120, starboard, was the only other aircraft aboard Saratoga and in the hangar. This aircraft, also "missing--sank with Saratoga," is presumably the airplane spotted by divers in the hangar area at the deck collapse, aft of plane 31840. [75]

|

| Two views of the Helldiver. Wings folded, an SB2C-4 is readied at the factory. In flight over the Pacific, a carrier task force below, an SB2C-4 shows the trim and features of the aircraft. (U.S. Naval Institute) |

|

| ABC-Television divers illuminate an SBF-4E "Helldiver" on Saratoga's hangar deck. This is aircraft BuAer #31894. (National Geographic Society, Bill Curtsinger) |

|

| Pilot's cockpit instrument panel, SBF-4E, BuAer #31850. Note that only the clock has been removed. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

The Helldiver was a wartime-production model designed to replace the prewar Douglass SBD Dauntless dive-bomber. The Helldiver had a combat range of 1,165 miles and was capable of 295 mph at 16,700 feet. The service ceiling was 29,100 feet. The SB2C-4/5 (same as the SBF-4E) Helldiver's wing span was 49 feet, 9 inches; the plane's length was 36 feet, 8 inches and its height was 13 feet, 2 inches. The empty weight of the Helldiver was 10,547 lbs.; the loaded weight was 16,616 lbs. The plane was powered by a Wright R-2600-20, 1,900-hp radial engine and was armed with two fixed forward firing 20mm cannon in the wings and two 0.30-inch machine guns in the rear cockpit. The plane carried up to 2,000 lbs. of bombs (1,000 internal/1,000 external) or eight 5-inch rockets. The Helldivers were used in mounting the air offensive against Japan; capable, they were difficult to handle, and earned the nickname "beast." One hundred SBF-4E (BuAer serial numbers 31836 to 31935), a Fairchild-Canada version of the Curtiss SB2C "Helldiver," were built in 1944-1945. [76]

Aft the aircraft the hangar is open; to starboard lie a number of Mk 13 torpedoes, some missing their warheads. Dating to the 1930s, the Mk 13 torpedo was the only aerial torpedo in use during World War II; it was not replaced until the 1950s. The Mk 13 was 161 inches long, 22.5 inches in diameter, and weighed 2,216 lbs. Propelled by a steam turbine, it developed 33.5 knots with a range of 6,300 yards. The control system was air/gyro.

The Mk 13 was replaced after 1950 by the Mk 14, an 84-inch long, 680-lb. weapon. [77] The torpedoes, like the bombs, were placed on the ship by the Bureau of Aeronautics for testing; the depth charges and torpedoes were prepared by BuAer in two ways; (1) in normal condition but without the booster and detonator but with the main charge, or; (2) with booster and detonator installed but with the main charge replaced by inert material. "Thus a sensitive explosive would not necessarily detonate a less sensitive charge." [78] Bureau of Ordnance photographs of the ordnance placed on Saratoga's hangar deck shows the inert material labelled "plaster." The torpedoes specifically are noted as having inert warheads, "but the flask is fully charged." Weapons noted in the BuOrd photographic documentation, but not yet observed during dives, include a rack of 5-inch High Velocity Aerial Rockets with Mk 6-1 heads and 149 nose fuzes and 164 base fuzes at frame 160, hangar deck, starboard; 11.75 "Tiny Tim" rocket, 2-100-1 Base Fuzes, marked "Inert" in photographs, at frame 162, hangar deck, port; and a mine, Mark 24 (secret), at frame 163, hangar deck, port. [79] Aft the torpedoes is a catwalk that has partially collapsed.

|

| A single Mk 13 aerial torpedo, on a cradle, inside the hangar. (NPS composite photo, Larry Murphy) |

|

| An Mk 13 torpedo suspended beneath a TBM-3E on USS Yorktown. (NPS, James P. Delgado) |

|

| Daniel Lenihan illuminates an unbroken light on the overhead inside Saratoga's hangar deck. The dark splotches on the overhead are patches of oil. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

|

| Radio equipment in the emergency radio equipment compartment at Saratoga's bow. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Aft of the planes, the hangar deck is empty except for ordnance mentioned above. At the bulkhead that ends the hangar, there is a large pile of piping and debris that could be remains of bunks from "Magic Carpet." NPS divers penetrated to this point and then into one compartment beyond. The compartment, listed as the aviation metal shop, was mostly empty. Expected lathes and other machinery were apparently removed. Vessel plans indicate further compartments aft. These compartments were not entered and their condition and contents are unknown.

The intakes for the boilers in the funnel area are clogged with debris, prohibiting visual access to the engineering spaces. Numerous open hatches on the starboard side were visually inspected; in all cases they opened into companionways that quickly terminated with gun hatches leading below or into the ship. These were not entered. The hatch of the handling room below the No. 3, 5-inch/38 caliber gunhouse stands open; limited visual inspection from outside indicated that the hoisting machinery is in place, as well as a number of cartridges in their aluminum containers.

USS PILOTFISH

The five-man team did one dive on the wreck of USS Pilotfish in 1989. A narrated video, site map, and still photographs were obtained.

Pre-Test Alterations

Known Pilotfish alterations include the installation of weights and wire rope moorings, as well as salvage fitting connections, that allowed the unmanned submarine to submerge and surface for the tests. The two periscopes were removed and the shears scope tubes were blanked out.

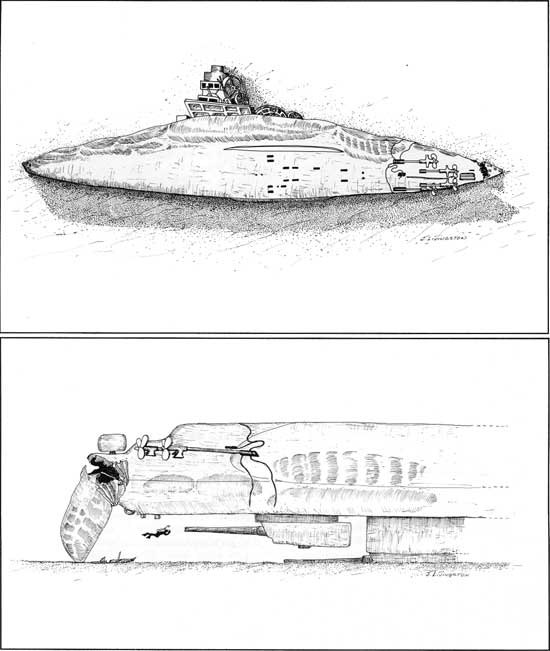

|

| Perspective sketch of Pilotfish. (NPS, Jerry Livingston) (click on image for a PDF version) |

Able Post-Blast Observations