|

National Park Service

The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb A Submerged Cultural Resources Assessment of the Sunken Fleet of Operation Crossroads at Bikini and Kwajalein Atoll Lagoons |

|

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Daniel J. Lenihan

In June 1988, while returning from a cooperative NPS/Navy diving operation in Palau, Dan Lenihan, Chief of the National Park Service Submerged Cultural Resources Unit (SCRU) was approached regarding a potential sunken ship survey at Bikini Atoll. Dr. Catherine Courtney of Holmes and Narver, representing her client, the Department of Energy (DOE), described the nature of the research problem in a presentation at the headquarters of U.S. Navy Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit One in Honolulu. Cdr. David McCampbell, Unit Commander, had been in communication with Dr. Courtney about the project for some time and recommended a joint effort using NPS and Navy personnel--a combination that had proved effective in numerous prior operations known collectively as Project SeaMark.

|

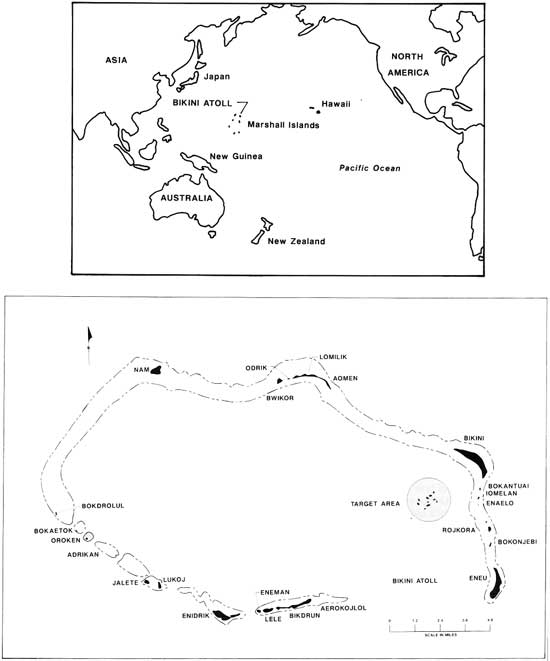

| Bikini Atoll. (NPS) (click on image for a PDF version) |

As formal requests for assistance were initiated and arrangements were made for a field operation in the summer of 1989, the NPS underwater team began preparations for one of the most challenging and compelling projects it has ever been asked to undertake. The ships of Operations Crossroads lying at the bottom of Bikini Atoll Lagoon and Kwajalein Lagoon are the remains of a fascinating event in American history, an event with international dimensions, including implications for the restructuring of geopolitical alliances in the latter part of the 20th century.

The notion that these ships might be considered as the focus for a marine park, which is the specific forte of SCRU, only further fueled the team's interest. Efforts to evaluate the ships as historical, archeological, and recreational resources for disposition by the Bikinian people began in August 1989 and resulted in the completion of this report in March 1991.

Although "ghost fleets" related to World War II exist at Truk Lagoon, etc., nowhere in the world is there such a collection of capital warships, augmented by a largely intact aircraft carrier, USS Saratoga, and the flagship of the Japanese Navy at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Nagato. Through chance or intent, vessels of great symbolic importance to the history of World War II were included in the test array and now reside at the bottom of the lagoon. These ships, all within a few hundred yards of each other, comprise an incomparable diving experience.

During the course of the project the team members, without exception, were impressed not only with the extraordinary cultural and natural resources of Bikini but with the compelling human dimension of the problem of displacement and resettlement of the Bikinian people. We hope the discussions in this report will help expand the range of options available to the Marshall Islanders in reestablishing their community on Bikini and other islands impacted from nuclear testing.

PROJECT MANDATE AND BACKGROUND

Under the terms of the Compact of Free Association between the Government of the United States and the Governments of the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia (Public Law 99-239), the United States, in Section 177, accepted responsibility for compensating the citizens of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, or Palau, for "any losses or damages suffered by their citizens' property or persons resulting from the U.S. nuclear testing program in the northern Marshall Islands between June 30, 1946, and August 18, 1958." The U.S. and the Marshall Islands also agreed to set forth in a separate agreement provisions for settlement of claims not yet compensated, for treatment programs, direct radiation-related medical surveillance, radiological monitoring, and for such additional programs and activities as may be mutually agreed. (99 Stat. 1812) In section 234, the United States transferred title to U.S. Government property in the Marshall Islands to the government of the Marshall Islands except for property which the U.S. Government determined a continuing requirement. (99 Stat. 1819)

Based on section 177, an agreement between the U.S. and the Government of the Marshall Islands relating to the nuclear testing programs was reached. Under the terms of this agreement, the U.S. Government reaffirmed its commitment to provide funds for the resettlement of Bikini Atoll by the people of Bikini, who were relocated during the first nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific, Operation Crossroads in 1946. Since then, studies that have focused on the eventual resettlement of Bikini have been and continue to be undertaken.

In July-August 1989 and April-May 1990, a team from the U.S. National Park Service traveled to Kwajalein and Bikini atolls to document ships sunk during the Operation Crossroads atomic bomb tests. The team was invited by the Bikini Council, the United States Department of Energy, Pacific Region, and Holmes and Narver, DOE's primary contractor in the Pacific and operator of DOE's Bikini Field Station.

The sunken ships at Bikini are the property of the people of Bikini. Title was transferred in the U.S. Marshall Islands agreement in accord with Article 177 of the Compact of Free Association; according to Article VI, Section 2 of the agreement:

Pursuant to Section 234 of the Compact, any rights, title and interest the Government of the United States may have to sunken vessels and cable situated in the Bikini lagoon as of the effective date of this Agreement is transferred to the Government of the Marshall Islands without reimbursement or transfer of funds. It is understood that unexpended ordnance and oil remains within the hulls of the sunken vessels, and that salvage or any other use of these vessels could be hazardous. By acceptance of such right, title and interest, the Government of the Marshall Islands shall hold harmless the Government of the United States from loss, damage and liability associated with such vessels, ordnance, oil and cable, including any loss, damage and liability that may result from salvage operations or other activity that the Government of the Marshall Islands or the people of Bikini take or cause to be taken concerning such vessels or cable. The Government of the Marshall Islands shall transfer, in accordance with its constitutional processes, title to such vessels and cable to the people of Bikini.

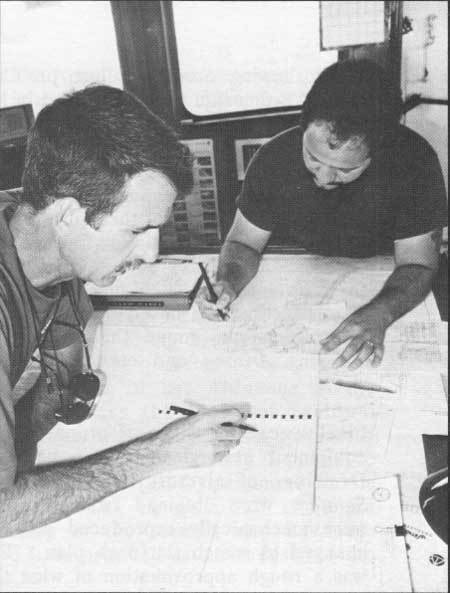

Under the Agreement, the U.S. Department of Energy conducted a study of the sunken ships in Bikini Atoll, in particular assessing leaking fuel and oil that may pose long-term environmental impacts that would result from the sudden rupture of tanks containing oil or fuel. Recommendations for the final disposition of the ships depended on assessments of their structural integrity and historic significance. The DOE requested the assistance of the U.S. Navy, Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit One, headquartered at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, to (1) determine the geographic location (latitude and longitude) of each ship; (2) mark the bow, stern, and midships section of each ship with spar buoys; (3) make a preliminary description of the condition of each ship; and (4) determine if the condition of the ships warranted an assessment of historical significance.

The U.S. Navy deployed MDSU 1 at Bikini between August 5-17, 1988. This activity, as well as general footage of Bikini and the ships, was filmed by Scinon Productions, which produced a special for PBS and for KGO-TV, San Francisco. Following this exercise and the concurrence of the Bikini Council, on December 21, 1988, the Department of Energy requested the services of the National Park Service to conduct an evaluation of the historical significance, marine park potential, and diving hazards associated with the sunken fleet at Bikini. Because the ships and test equipment submerged in Bikini Lagoon are an immensely valuable cultural resource deserving thorough study, and the Service's Submerged Cultural Resource Unit is the only U.S. Government program with experience in this work, the National Park Service agreed to assist DOE. At the same time, MDSU 1 was redeployed at Bikini with EOD Mobile Unit One to continue marking wrecks and to assess and safe live ordnance in, on, and around the ships.

|

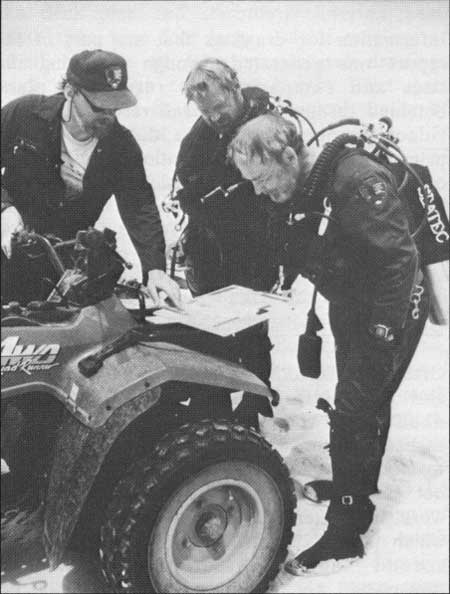

| Commander David McCampbell, USN (left), led the Navy effort to locate and plot the wreck locations. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

The National Park Service team was led by Daniel J. Lenihan, Chief of the Submerged Cultural Resource Unit, and included as team members NPS Maritime Historian James P. Delgado, Head of the National Maritime Initiative; SCRU Archeologist Larry E. Murphy; Archaeologist Larry V. Nordby, Chief of the Branch of Cultural Research, Southwest Regional Office; and Scientific Illustrator Jerry L. Livingston of the Branch of Cultural Research. The same team assembled in Honolulu, Hawaii, in early August 1989 and from there traveled to Bikini by way of Kwajalein. The team returned for a second and final field season in late April-early May 1990.

Of the original array of target vessels, 21 ships (counting eight smaller landing craft) were sunk in Bikini Lagoon during the Able and Baker atomic bomb tests of July 1 and 25, 1946. A number of the remaining vessels, among them the former German heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen (IX-300), which "survived" the tests, were towed to Kwajalein Atoll for decontamination and offloading of munition. Progressive flooding from leaks, however, led to the capsizing and sinking of Prinz Eugen in shallow waters in Kwajalein Atoll Lagoon in 1946. Another target vessel, LCI-327, was stranded and "destroyed" on Bascombe (Mek) Island in Kwajalein Atoll in 1947. These two vessels comprise a secondary deposition of Crossroads target ships that are accessible for study.

The NPS team was able to visit nine of these 23 vessels and document them to varying degrees. The team subsequently evaluated two other vessels utilizing the Navy's Remote Operated Vehicle (ROV) video coverage of them. The major focus of the documentation was the aircraft carrier Saratoga (CV-3) at Bikini; a lesser degree of documentation was achieved for the battleships Nagato and Arkansas (BB-33), the submarines Pilotfish (SS-386) and Apogon (SS-308), YO-160, LCT 1175, LCM-4, and the attack transports Gilliam (APA-57) and Carlisle (APA-69) at Bikini, as well as the cruiser Prinz Eugen at Kwajalein. In every case, the NPS found sufficient cause to determine that these vessels are indeed historically and archeologically significant.

|

| The Navy's Explosive Ordnance Demolition Unit One safed a depth bomb by "gagging" its live fuse. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

This report documents the pre-sinking characteristics of each of the vessels, as well as an assessment of their careers and participation in Operation Crossroads. In the case of the nine vessels visited by the NPS team and the two ROV-dived vessels, a site description based on the assessment dives and documentation efforts is included. The report includes the results of several weeks of research that provided more concise information pertaining to target vessel characteristics, specifically Crossroads modifications and outfitting. Among the more interesting archival discoveries was that the firing assemblies for some test ordnance on the test ships were incomplete, with inert elements (plaster) replacing either the main or booster charges.

METHODOLOGY

Background Research

In preparation for the project, background material on Operation Crossroads and the individual target ships included in the tests was obtained by historian James Delgado through several sources. Historical information about each vessel's characteristics, history, participation in the tests, and the circumstances of its sinking were obtained, as were materials pertaining to test planning, logistics, and results.

In preparation for field activities, the plans most likely to reflect the final configuration of armament and deck features present on Saratoga were sought. A set of microfilmed plans showing Saratoga's last pre-Crossroads refit at Bremerton Naval Shipyard in May 1945 was obtained. From these and published plans of the ship, a deck plan and starboard elevation of the carrier as it was configured at the end of the Second World War were available. The scale of these drawings was too small to serve as a basis for field work, so they were expanded using a Map-O-Graph machine to a final scale of 1/8-inch per foot (1:96). This selection was based on the preference of illustrators, who found this scale ideal when mapping Arizona and other ships of similar size.

Finally, scale drawings of ordnance and radar equipment were gleaned from naval manuals. Drawings of aircraft known to be aboard Saratoga were obtained from books. These were mechanically reproduced and the scale changed to match the deck plan. The result was a rough approximation of what the vessel would have looked like on the eve of Operation Crossroads, expressed in drawings of the deck plan and starboard elevation, each more than nine feet long. Mylar tracings of small sections of their conjectural drawings were carried on each dive by the illustrators and altered to fit the archeological reality of the ship's present appearance.

Site Description and Analysis

To develop a narrative presentation of findings from the research, archeologists Dan Lenihan and Larry Murphy, and historian James Delgado, swam through each site and recorded observations or notes after the dive or on videotape during the dive. To permit filming, a special experimental hookup was designed before the project to connect a full face mask (AGA) to a small underwater video camera. The mask was installed with a microphone that permitted the diver to speak directly onto a videotape as he panned the site with the camera. This permitted onsite recording of field observations and also permitted much easier referencing of the viewer to the location of the image on the site. On large sites, recording the location of the camera image has been a consistent problem.

In addition to personal observation on the site, the Navy's Bureau of Ships 1946 description of some of the vessels helped separate primary deposition from later site formation processions. Information on biological communities now present on the site was obtained through video imaging for examination both at Bikini and on return to Santa Fe.

|

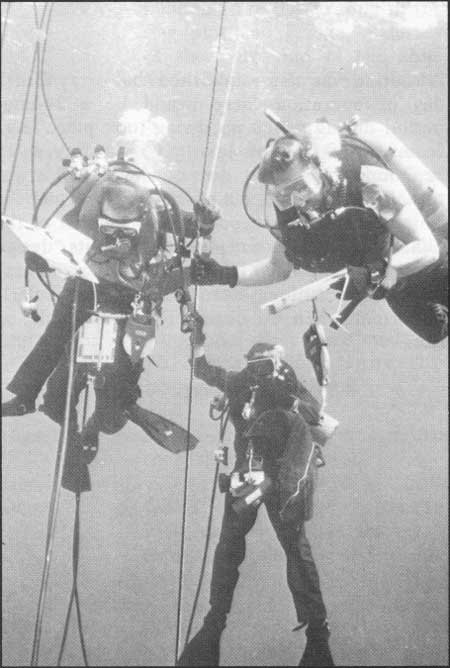

| The depth at which the wrecks lie, and the amount of time required for meaningful observation and documentation compelled lengthy oxygen decompression stops. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

Information generated in this manner was also used for assessing recreational potential. Although the team was well equipped to assess normal sport diving hazards (given the extensive shipwreck diving backgrounds of the members), it was not qualified to evaluate the volatility or status of live ordnance in the vessels or address the issue of residual radiation hazards without help from specialists. Cooperation with U.S. Navy Explosive Ordnance Demolition (EOD) personnel on site was very useful in gaining such an understanding of the former, and Lawrence Livermore Labs provided extensive insights into the latter.

"Imaging the Ships"

Information for drawings that are part of the report was generated through sketching the sites and comparing the results to plans obtained through the archival research. Some videotape obtained in the dives was taken primarily as an aid to illustration. Unlike most other situations in which physical baselines have been used by SCRU to map sites, there was enough integrity to the vessel fabric that features of the ships themselves could be used as integral reference points.

|

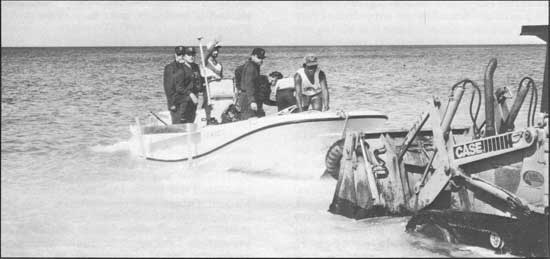

| Boat launching by front-end loader. The NPS team prepares to depart for a day's diving. Eric Hanson is at the helm, while Edward Maddison prepares to release the boat. |

Operational Diving Procedures

Given the 180-foot maximum depth of the ships and the intensity of the diving operations needed to accomplish the objectives of assessing and documenting the ships at a working depths usually well over 100 feet, if not deeper, certain deep diving procedures were implemented. Special dual manifolds which permitted total redundancy of first and second stages of breathing systems were transported to the job site from Santa Fe. These were used to arrange cylinders supplied by DOE into double tank configurations. The diving day was divided into two dives per team with staged decompression anticipated on both dives. The first dive of the day was always planned to be deeper or as deep as the second dive.

An in-water oxygen decompression system was also brought from Santa Fe to allow a large margin of safety in decompression profiles. Standard U.S. Navy air tables were used in decompression, but oxygen was substituted as the breathing gas for 30-, 20-, and 10-foot stops. Emergency evacuation procedures were established and after the Navy arrived on the scene during the first field session, a routine system for accident management was established that involved the use of their Diving Medical Officer and recompression chamber. During the 1990 field session no Navy medical facilities or chamber were available, so evacuation to Kwajalein would have been necessary.

A routine was also established that every fourth day of operation there would be a 24-hour period during which no diving took place, e.g., from "up" time of last dive on day 4 to beginning of the first dive on day 5. This was to help mitigate effects of "Safari Syndrome" in which the 12-hour decompression model of the U.S. Navy tables is pushed past its design limits for multi-day repetitive diving. These special precautions were deemed particularly important when no chamber was available on site.

|

| After diving LCT-1175, Daniel Lenihan, Larry Nordby, and Jerry Livingston compare notes on the sketches and measurements made by the scientific illustrators. (NPS, James P. Delgado) |

ACTIVITIES

| 1989 Field Season | |

| August 8-10: | The team traveled from their duty stations in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Washington, D.C., to Kwajalein, Marshall Islands. |

| August 11: | Layover in Kwajalein. Team traveled around Kwajalein with public affairs liaison officer visiting WWII sites. |

| August 12: | Prepared for departure to Bikini, but Air Marshall Islands came in overbooked and would not take the team to Bikini. Obtained access to a boat during latter part of the day and snorkeled the wreck of Prinz Eugen. |

| August 13: | The plane did not come, so the Holmes and Narver representative arranged for team to dive on Prinz Eugen. The team conducted a reconnaissance survey of the site, obtaining video footage, photographs, and a sketch. It was discovered that the description of the ship in Jane's Fighting Ships was incorrect in that it stated the ship had four screws rather than the three it has. On the basis of this dive, a section on Prinz Eugen was included in the results section of this report and specific management recommendations will be made for transmission to the Base Commander. |

| August 14: | Once again Air Marshall Islands (AMI) decided not to fly. Kent Hiner, Holmes & Narver's project manager, radioed an AMI plane en route to Kwajalein from some other point and negotiated a flight to Bikini before they took their scheduled return flight to Majuro in the Marshall Islands. After lunch, a first assessment dive was made on the wreck of Saratoga to a maximum depth of 100 feet. |

| August 15: | During the first full day of dive operations at Bikini, the team made an assessment dive on Saratoga and commenced taking observations for the site plan and starboard profile of the ship. The starboard side was reconnoitered at 140 feet; the elevator was entered and its immediate area investigated, as was the forward section of the ship, particularly the 5-inch gun mount. |

| August 16: | Dives on Saratoga focused on assessments of the island, including the penetration of the flag plot and bridge, a survey of the port side of the ship, and the penetration of the hangar. |

| August 17: | Mapping of the after area of the ship disclosed the first major damage to Saratoga from the tests. A reconnaissance of the bottom of the lagoon at the stern and additional penetration of the bridge were completed. |

| August 18: | Additional dives were made on Saratoga to continue the mapping of the wreck. |

| August 19: | Saratoga's island was more thoroughly investigated. |

| August 20: | Dives on Saratoga began to focus on mapping the starboard side of the ship for the profile drawing. |

| August 21: | Dives completed the preliminary mapping of Saratoga, focusing on the forward section, midships area, and island. |

| August 22: | Entire team dived on Arkansas, resulting in video and a sketch of the wreck. The dive assessed the more intact port side of the battleship at the 160-foot level and the keel at the 140-foot level. |

| August 23: | A dive was made on Pilotfish, using for the first time the experimental AGA-video hookup. Delgado narrated his notes on the dive directly onto a tape at 150 feet, accompanied by Lenihan, while the other team members sketched and photographed the boat. The second dive of the day, with Delgado again in the AGA, visited Nagato, exploring the after section of the ship. |

| August 24: | The only dive of the day was made to Gilliam, the accidental zeropoint ship for the Able Test bomb's detonation. The team swam the length of the ship, sketching and photographing it. Larry Murphy departed with the majority of the equipment to catch a Military Air Command (MAC) flight to Honolulu in order to assure loading of that equipment for another operation in the Aleutians. |

| August 25: | The team made the last dive of 1989 on Saratoga, penetrating the hangar and more extensively documenting the aircraft inside. That afternoon, remaining equipment was packed for departure. |

| August 26: | The team made an early afternoon departure from Bikini, flying via AMI to Kwajalein. From Kwajalein, the team members separated--Lenihan and Nordby to Santa Fe; Livingston and Delgado to Guam. |

| 1990 Field Season | |

| April 25-27: | The team travelled from their duty stations in Santa Fe, and Washington, D.C., to Honolulu, and then to Kwajalein. |

| April 28: | Layover in Kwajalein. The team made a dive on Prinz Eugen and obtained additional photos and information for a map of the wreck. |

| April 29: | The team boarded the DOE research vessel G. W. Pierce and sailed from Kwajalein for Bikini. |

| April 30: | At sea most of the day. Bikini was sighted at 4:00 p.m., and at 5:20 p.m., anchor was dropped off the island. The team was shuttled ashore. |

| May 1: | First dives were made with team members working on the island and in the hangar of Saratoga. |

| May 2: | Mapping Saratoga continued. Lenihan and Murphy penetrated the hangar to its aft bulkhead, locating additional torpedoes, rockets, and homing torpedoes (depth of 130 feet). Five-inch shells in the handling rooms and the open twin 5-inch/38 mount were explored aft of the stack by Delgado. Afternoon dives focused on the bow; the windlass and emergency radio compartments were penetrated. Delgado and National Geographic Society writer John Eliot dove on a shallow water inshore wreck, which proved to be LCT-1175. |

| May 3: | Documentation of Saratoga continued. Arkansas was dived on and port casemate penetrated by Lenihan and Murphy at a depth of 170 feet. Wreck of LCM-4 snorkeled and identified near that of LCT-1175 by Delgado. |

| May 4: | Lenihan, Delgado, and Murphy swam under Nagato from stern to the aft end of the bridge (depth of 170 feet). Nordby and Livingston continued mapping operations on Saratoga, and Lenihan and John Eliot dived on YO-160 in afternoon, videotaping deck machinery. |

| May 5: | Lenihan, Murphy, and Delgado continued documentation of Nagato, videotaping and photographing upturned bridge, forward turrets, and stern. Livingston and Nordby continued mapping operations on Saratoga (portside). Entire team worked on Saratoga in afternoon. |

| May 6: | Entire team worked on documentation of LCT-1175. |

| May 7: | Lenihan and Murphy worked on Nagato bow; Delgado, Livingston, and Nordby worked on port bow of Saratoga. |

| May 8: | Entire team conducted "blitz" dive on Nagato stern (depth of 170 feet) obtaining sketches, video, and photography. In afternoon, focus shifted back to completion of work on Saratoga. |

| May 9: | Murphy conducted training dive for Bikinians, teaching them underwater oxyarc cutting techniques using car battery and oxygen. Lenihan was able to meet briefly with Bikinian elders and Jack Niedenthal (Bikini Liaison) during layover of AMI flight on Enyu. Some of the project results including drawings were reviewed. |

|

| The Bikini Council sent a dive team to participate in the documentation of the ships. Here, the team takes measurements to the corner of the blast gauge tower next to Saratoga's elevator. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

|

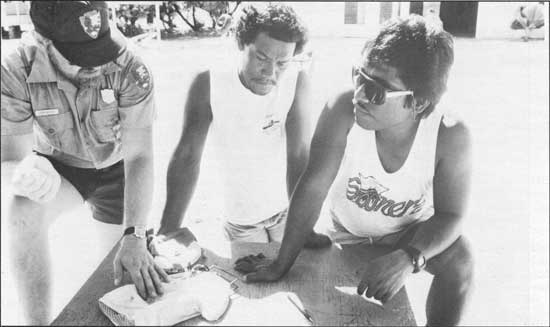

| The system of trilateration used to map the wrecks is being discussed by Edward Maddison, Wilma Riklon, and Larry Nordby. (NPS, Larry Murphy) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

swcr/37/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 22-Sep-2008