NPS The Civil War Comes To Macon During "The War Between the States", the newly-founded city of Macon was threatened with destruction not once, but twice when Union and Confederate forces met just across the river from the city. Both conflicts took place here on the grounds of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park. Today, the Dunlap trail leads to one of the few surviving Civil War earthworks in Macon; a reminder of another time in history adding to the heritage that is Ocmulgee. The Battle of Dunlap Hill On July 27, Major General William T. Sherman had sent 9,000 Union cavalrymen riding south in two columns. Their orders were to join forces at Lovejoy and wreck the vital Macon railroad that fed and supplied the Confederate army defending Atlanta. Major General George Stoneman led one of these columns through Covington and Monticello, intending to march down the east side of the Ocmulgee River before joining the other column led by McCook. To his surprise and dismay, Stoneman soon discovered there were no bridges along that muddy stretch of the Ocmulgee. Reluctant to rejoin Sherman without accomplishing anything, he continued south, hoping to capture Macon and perhaps even liberate the 35,000 Union soldiers imprisoned at Camp Oglethorpe and Andersonville. The Battle of Walnut Creek The second military encounter between Union and Confederate forces near the city of Macon was also at the Dunlap Farm.This skirmish took place on November 20-21, 1864. The action was a diversionary ploy for the major troop movements of General Sherman's Union force through Middle Georgia. In October 1864, as a reaction to "The Stoneman Raid" and news of the destruction Federal troops had inflicted throughout Georgia, additional defense construction was made for the city of Macon. It is believed that the gun emplacement on the Dunlap Trail was built as a part of this additional defense system. But regardless of when the earthwork was constructed, its 12-pound Napoleon gun and 8 others played an important role in the "Battle of Walnut Creek." When Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick and his men reached Macon, they were met by elements of Wheeler's Confederate Calvary made up of the 1st and 2nd Convalescent Regiments, the 24th Tennessee, Captain Albrough's command, Captain Atkins' company and nine cannons. A Union calvaryman later explained: "The regiment was not engaged again until the arrival of the command at Macon... when during the demonstration made by General Kilpatrick... the regiment was ordered to make a saber-charge along the Clinton and Macon Road, and from which the enemy were firing. The distance to reach the guns was something over half a mile, along a road through deep woods, which concealed the enemy's guns and their works. "The regiment... charged along the road, reached the enemy's guns, which were in a redoubt, completely blocking the road, there being room only for two horses to enter the works abreast. In the rear of, and also extending from both flanks of the redoubt, were long lines of breastworks and rifle pits, filled with infantry. On the left of the road there was also a battery commanding the road and the point from which the regiment charged it. As the head of the column entered the redoubts, the first line of the enemy's infantry... seemed to be stampeded. The second line, however, were seen advancing from the woods... and seeing that the guns could not be removed, and that there was barely time to withdraw the regiment before the rebel infantry would be upon us, I ordered the column to retire under fire from enemy guns." Today, the Dunlap Trail is a short, pleasant walk from the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park's Visitor Center. At the end of the trail you will be able to see one of the few remaining Civil War earthworks in Middle Georgia. Although not open to the public, the adjacent Dunlap House was once occupied by Union soldiers. The Dunlap Mound was the "hill" for which Macon's first Civil War battle was named.

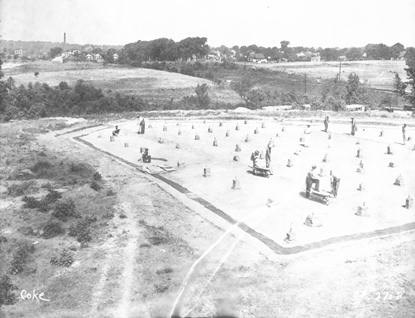

NPS PHOTO The Largest Archaeology Dig In American History The largest dig ever conducted in this country occurred here at Ocmulgee and the surrounding area. Between 1933 and 1936, over 800 men in Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration (WPA), Civil Works Administration (CWA), Federal Emergency Relief Administration (ERA & FERA), and later the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) excavated under the direction of Dr. Arthur R. Kelly from the Smithsonian Institute. Kelly was the only archaeologist at the Ocmulgee camp and conducted evening training courses for the men. Hundreds of thousands of artifacts were discovered including pottery, pottery shards, metals, arrowheads, spear points, stone tools, pipes, bells, jewelry, seeds, bones, etc. –some of which are on display in the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park's museum or stored in the museum curatorial. This dig helped piece together a timeline of people who lived on the Macon Plateau between 12,000 BCE and 1800 CE. Each of the major periods were represented here at Ocmulgee. Altogether, 2.5 million artifacts were found, with 800 men working at one time. The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) Large-scale archeological excavations at Ocmulgee Old Fields in Macon, Georgia began in December of 1933. The site was declared a National Monument in 1936. In 1937 the National Park Service, along with U.S. Congressman Carl Vinson, General Walter Harris, and Dr. Charles C.Harrold, completed a list of needed development projects including construction of a museum, restoration of archeological features, access roads and parking, tree planting, and fence construction - all to include the detached Lamar Site, where a levee was also needed. Major construction projects included building their own camp, restoring the 1,000-year-old Mississippian Era Earth Lodge, beginning work on a 40,000 square foot museum and administration facility (not finished until after World War II), constructing and paving two miles of roads including culverts and curbing, building parking lots, and preparing trails including a bridge between the museum and Earth Lodge that has become a local landmark. Additional laborious details at the detached Lamar Site (two miles south of the main site and including two large mounds) involved levee construction along with clean-up after the excavations. The clean-up, or rehabilitation effort, included the non-dramatic, backbreaking work of refilling excavation ditches.The young men labored in the heat of summer and in the cold of winter. The bleak days of the Depression and the loneliness of family separation were blended into cheerful days and new comradery through necessity and youthful optimism. Concrete was hauled in wheelbarrows, logs were moved by human power, and even stone-quarried without modern equipment. At the Earth Lodge, enrollees puddled clay in large pits, mixed in straw, and then applied the mixture to the inner concrete wall to simulate the Mississippian architecture. The public was admitted to this historic structure on November 1, 1937 after the CCC 'boys' completed the steel walkway and installed electric lights. Park projects continued throughout 1940. A wooden fence was installed around much of the park. At the entrance, a building resembling the design of old Fort Hawkins (1806) was added for the CCC visitor guides. Work continued on the large protective shelter over the Funeral Mound. |

Last updated: October 23, 2023