|

Women have always played a tremendous role on the Natchez Trace Parkway. They lived and worked along the Old Trace. They saw its importance and wanted to see it preserved and protected forever. Also, there are the women who continue to preserve and protect it today for future generations to enjoy. Learn more about these women below!

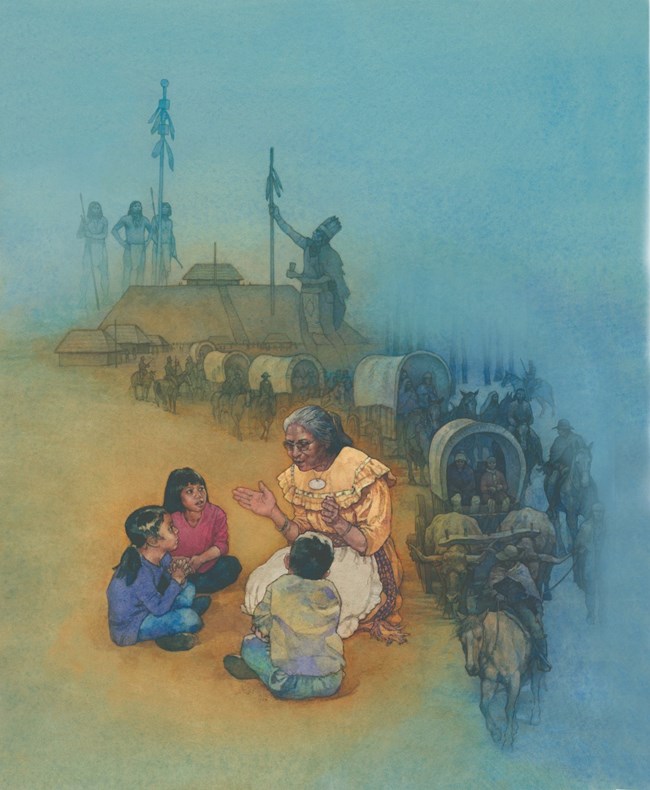

NPS Artwork, Artist Harlin The Chickasaw and Choctaw, while two separate tribes, shared their ideals on linage. Both tribes trace their heritage through the mother’s line. This meant that children inherited from their mother, including the clan and family they belonged to. Woman managed their own resources and homes; a home was the women’s not the man’s. If separation occurred between spouses, the male would move out of her home and back with his family. Women were treated with respect and considered extremely important within society. The Natchez people maintained a caste like system. The ruling class, the Suns, acquired their status through the female line. Interestingly, the nobility were required to marry outside of their class,a practice not done within most caste systems we know of.

The Old Trace was signed into a postal road by President John Adams. It became a popular place for stands, or inns,to populate along. These stands became safe havens with a place to rest and a meal to eat during the long journeyup or down the Old Trace. Many women worked at these stands, normally alongside their husbands.

NPS Photo, 2015 Polly was a landowner and businesswoman, who saw Mount Locust prosper under her guidance. Not a lot of women could do this in the early 1800s. She continued to reside and work the estate until 1847 when she die at the age of 80 years old. Polly was buried in the Chamberlain family cemetery.

Polly was not the only lady who ran her homeand business along the Old Trace. Up on the northern end, in Tennessee, there was Dolly Cross Gordon (1794-1859). Dolly, and her husband John, ran a trading post and ferry at their home. John Gordon was the leader of a scouting party for Andrew Jackson and named the “Captain of Spies". John was repeatedly called away at the request of Andrew Jackson, especially during the War of 1812. Dolly managed the family’s business dealings and oversaw the building of their brick home known today as Gordon House, which still stands at milepost 407.7. John died soon after the war in 1819, leaving behind Dolly and their 11 children. Dolly worked the farm land with the help of her sons and enslaved people, producing cotton, cattle, and hogs. Dolly lived out the rest of her life at Gordon House, where she died in 1859. At the time of her death her son-in-law wrote,“She bore the burdens of their home, and was as brave and heroic as he (her husband) was”.

NPS Photo, 2003 In 1825, the Academy experienced great success under the leadership of Caroline Thayer. Thayer had published articles on educational topics and took a great interest in educational theories and practices. Thayer’s methods attracted new students and saw an expansion of the buildings in the 1820s. Many sing her praises and all that she accomplished while charge of the school. However, in 1845, it closed its doors. This was due to several reasons, but mostly due to the state capital changing from Natchez to Jackson. In the late 1870s, a fire reduced the site to ruins. After the Civil War, the Old Trace laid forgotten in some areas. By the early 1900s, there was a push to preserve the Old Trace because of the tremendous amount of history the old road saw. This push was started by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), perhaps inspired by John Swan’s article in “Everybody’s Magazine” about the Old Trace. In 1908, Elizabeth Jones, the Mississippi state regent for the DAR, started the movement to trace the route of the Old Trace and urged for the placement of monuments and markers to relate to the history. By 1933, every county the Old Trace passed through had a marker. This act gave great attention to the Old Trace, eventually leading to its designation as the Natchez Trace Parkway in 1938. You can see a lot of these markers along the Parkway today at various pull offs. Keep an eye peeled for them during your travels!

NPS Photo Byrnes invited national leaders to her home in Natchez, where she steered the conversation to the Natchez Trace Parkway. Guests were given a tour of her “war room” which had paintings of the complete Parkway and progress maps. The guests left fully committed to supporting the project. A friend commented that the Natchez Trace was paved with “Moonshine and meatloaf”. In 1935, Byrnes became the president of the Natchez Trace Association, which she served on for twenty-five years. During that time, she spent countless hours writing letters and articles emphasizing the parkway’s importance. On November 9th, 1951, the first part of the Parkway opened, 65 miles from Jackson to Kosciusko. By 1968, Byrnes had traveled over 300 miles of completed Parkway. Byrnes often said, “I want to ride on the Natchez Trace all the way before I have to ride on the golden streets”. However, the Parkway was not finished by the time of her death in 1970. Explore More! If you would like to learn more and find locations along the Natchez Trace Parkway where this history happened, check out our webpage Discovering Women's History on the Natchez Trace. |

Last updated: June 21, 2022