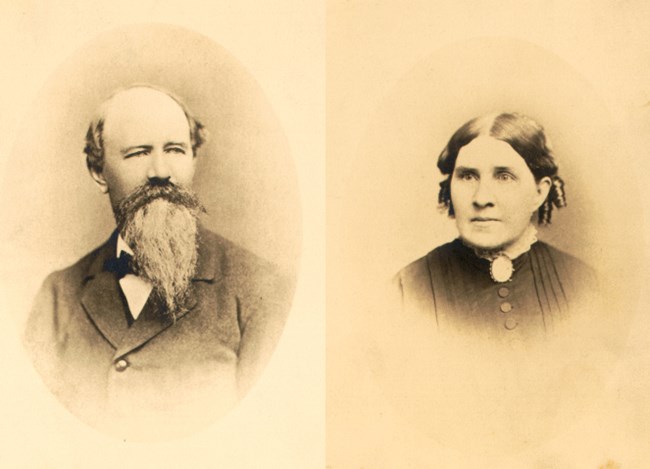

John T. Worthington was born in 1826 into an extended Frederick County family of prominent farmers. John married Mary Ruth Delilah Simmons in 1856 and the couple eventually had four children, three sons (John, Glenn, and Clark) who survived childhood and a daughter (Florence) that died in infancy. During the Battle of Monocacy, Confederate troops crossed the Monocacy River onto the Worthington Farm, initiating three attacks from the farm fields. Worthington and his family took refuge in the cellar, and through the boarded-up windows, six-year-old Glenn Worthington watched intently as the fighting raged in front of the house. In his account of the battle, Fighting For Time, Glenn Worthington recalls that, “Glimpses of blue could be seen as they passed windows. More than one received his death wound close to the house and fell there to die, in Worthington yard.”

After the battle, John Worthington and his family assisted with the care of the wounded soldiers. Glenn and his seven-year-old brother Harry were sent into the nearby fields to gather sheaves of wheat for use as a bed for a wounded Confederate soldier. While the wounded were being cared for, other Confederate soldiers gathered the muskets that had been thrown away by the retreating Union soldiers. The muskets were placed in a pile in Worthington’s back yard and set on fire, leaving only the gun barrels and bayonets. Glenn desired one of these bayonets as a souvenir. He procured a stick and began to drag the bayonet from the embers, and as he stooped to retrieve his prize, an ember touched a discarded paper cartridge which exploded in his face. A Confederate soldier carried him, blinded and yelling, into the house. Luckily Glenn’s eyesight was not damaged by the explosion and he made a full recovery. After the Civil War, John Worthington continued to be a successful farmer, transitioning from reliance on enslaved labor to paid labor. The 1870 census reveals that in addition to the immediate members of the Worthington family, there were five additional people living at Riverside Farm. Rolander Sides is listed as a 14-year-old, white farm laborer. The census records that Rolander had attended school in the last 12 months. Fanny Rollins is recorded as a 16-year-old black domestic servant. Below her is listed one-year old John T. Rollins who was presumably her son. Estelle Garnet is listed as an 18-year-old, mulatto domestic servant. She may have been literate since the record does not list her as illiterate. Estelle's place of birth is recorded as Virginia. James Gray is listed as 19-year-old and a farm laborer. None of the seven people enslaved by Worthington in 1860 appears to still live on the Worthington household/farm in 1870.

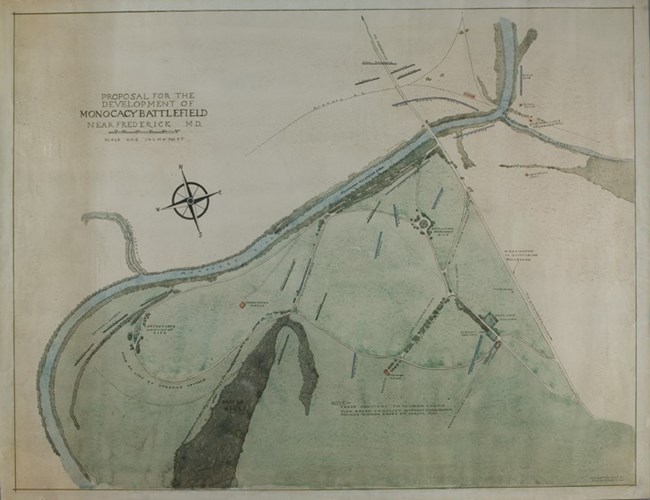

Impressed with the scene that was forever etched in his memory, Glenn grew up with a strong interest in the battle and its importance in saving Washington, D.C. In the late 1920s, he began to work for the creation of Monocacy as a battlefield park. He joined with others to form the Monocacy Battlefield Association and wrote a history of the battle entitled Fighting for Time. Worthington saw his dream of a battlefield park become a reality shortly before his death in 1934, when Congress established the park “to commemorate the Battle of Monocacy.” Due to a lack of funds, however, Monocacy Battlefield was a park in name only. Due to increasing development pressure, in the 1970s the National Park Service was finally authorized to establish the battlefield boundary, and began purchasing land after 1980. The Worthington Farm became part of the park in 1982, preserving for future generations the stories of both the soldiers who fought here and the family that called the farm home. |

Last updated: May 4, 2024