Maryland State Archives

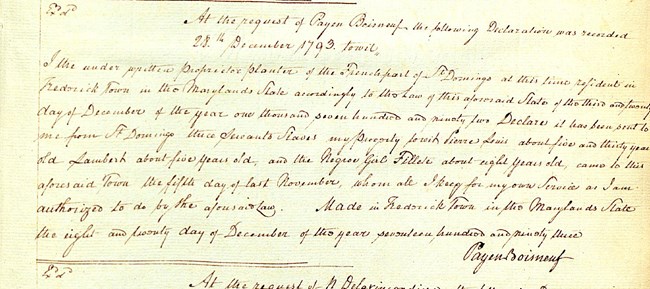

Pierre Louis was born around 1758, most likely in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Little is known about Pierre Louis's life in Saint-Domingue, where he was enslaved by a Frenchman named Pierre Payen, but the entire economic viability of the colony hinged upon the practice of slavery. In 1789, the population of Saint-Domingue included 31,000 whites, 28,000 free blacks, and 465,000 enslaved persons. By the 1780s, Saint Domingue produced 60% of the world's coffee and 40% of the world's sugar. Pierre Payen and his brother Jean Payen de Boisneuf owned at least three large sugar plantations and would have enslaved hundreds of Africans and their descendants to operate their plantations. It is unknown if Pierre Louis lived at one of these plantations or at the Payens' townhome in Saint Marc, but his skills a a wig-maker most likely spared him from working in the fields. In 1791, two events changed Pierre Louis's life: Pierre Payen died and the Haitian Revolution began. Jean Payen was in France when his brother died and he inherited Pierre Payen's assets. In August of of 1791, the first uprisings of enslaved people seeking freedom began in the Northern Province of Saint-Domingue. Instead of returning to Saint-Domingue, Jean Payen went to the United States in November 1791 to appeal for aide to put down the slave uprising in Saint-Domingue. It is unclear when exactly Jean Payen sent for him, but by November 1793 Pierre Louis had been taken from Saint-Domingue and brought to the United States.

Maryland State Archives

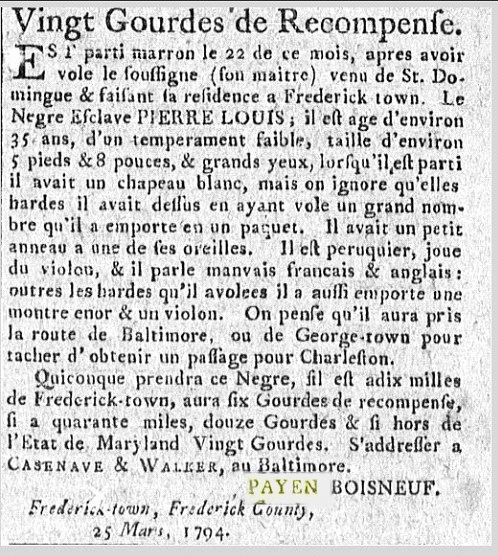

Baltimore Daily Intelligencer, April 2, 1794 Pierre Louis's skills as a violinist and a wig-maker/hair dresser and his ability to speak French and English suggest that he was a body servant. As a body servant, Pierre Louis would have had close contact with Pierre and Jean Payen. The value Jean Payen placed on Pierre Louis is reflected both in the multiple advertisements and in the $20 gourdes/dollars reward (more than $500 in 2020). The later advertisements, in addition to being in English, speculated that Pierre Louis might have fled to Philadelphia instead of Charleston; indicating that Jean Payen was actively seeking Pierre Louis. Pierre Louis's escape was short-lived, as he was picked up in May 1794 as a vagrant on the streets of Philadelphia. Philadelphia was one of the main centers of French refugee life in the United States at this time; while it is unknown how or if Pierre Louis knew this, it was more likely that he could have started a life as a French speaker there. Unfortunately for Pierre Louis, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 required the Philadelphia courts to return him to Payen in Maryland.

Pierre Louis's attempts to gain his freedom did not stop after his return to Maryland. On March 31, 1797, Pierre Louis filed a petition for freedom against Jean Payen de Boisneuf and Victoire dela Vincendiere. How Pierre Louis knew of or had access to these legal maneuvers is unknown, but he appears to have garnered the support of several prominent local citizens in his quest for freedom. A neighboring property owner, James Marshall, provided a recognizance of £120 on behalf of Pierre Louis to allow his petition to be heard in court. George Murdock, a leading Frederick citizen, served as a witness for Pierre Louis. Both James Marshall and George Murdock were enslavers. Joshua Dorsey, a local attorney and prominent citizen, served as his attorney. Pierre Louis's argument for freedom hinged on the 1792 law governing the importation of enslaved laborers from Saint-Domingue to Maryland. In order to prevent enslaved laborers with rebellious or unknown temperments from being brought to Maryland and possibly fomenting unrest, the law limited the type and number of enslaved persons that French refugees could bring with them. The law only allowed personal domestic or household enslaved "servants." Pierre Louis argued that since he had not belonged to Jean Payen de Boisneuf when he was in Saint-Domingue, but to his brother Pierre Payen, Pierre Louis had been illegally brought to Maryland. Jean Payen had not taken posession of Pierre Louis in Saint-Domingue, but instead had sent for him from the United States. As such, it was impossible for Pierre Louis to have personally served Jean Payen in Saint-Domingue. Twelve Frederick County jurors agreed with Pierre Louis and granted him his freedom. Jean Payen immediately filed an appeal that was heard in Annapolis, Maryland, by the General Court of the Western Shore in October of 1799. The Court upheld the earlier decision, making Pierre Louis a free man. Pierre Louis's life after securing his freedom is unclear. It is also unclear whether he received the 12 shillings and 518 pounds of tobacco he sought from Jean Payen to cover his court costs. On July 29, 1824, noted Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht wrote, "Died last night or this morning, aged about 65 years, Negro Peter Loui commonly called 'French Loui'. He was a native of Santa Domingo and came to this country when the insurrection of the blacks took place in that Island in 1793. He was of course a Roman Catholic, by persuasion, on which graveyard I presume will he be interred." ReferencesMaryland State Archives 2005 Best Farm; Monocacy National Battlefield Cultural Landscape Report. Frederick, Maryland. |

Last updated: August 6, 2020