Introduction to Twin Cities GeologyThe best way to see the geology of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area is from a boat or canoe leisurely drifting down the Mississippi River. The next best way is traveling down the Great River Road, a road that stretches along the Mississippi River from its source in Lake Itasca to the Gulf of America. You can follow this scenic road along the entire National River from the northern boundary near Anoka, MN, through the Twin Cities and down to Hastings, MN. While you enjoy the scenic 72 miles of federally designated corridor, be sure to make frequent stops to look at the rocks along the way. The bluffs that you see cut by the Mississippi River represent eons of geologic history..and set the stage for more recent human history.

The Mississippi River has spent the last 12,000 years carving cliffs into the ancient rocks. These cliffs of soft, white sandstone (called the St. Peter Sandstone) are the lithified remains of the expansive beaches of an Ordovician sea that covered the mid-west 450 million years ago. A look at these sand grains through a magnifying glass reveals sand that has been washed clean and made perfectly round from millions of years of tidal action. Small holes in these cliffs are produced naturally by wind and rain and provide homes for birds. Larger ones were created by people mining the sand for glass bottle production.

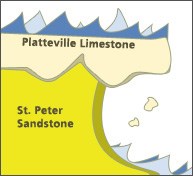

Above this fragile strata is the hard, creamy limestone (called the Platteville Limestone) that caps the cliffs. This resistant layer contains the fossils of snails and clams that lived and died on the floor of an ocean that covered Minnesota 400 million years ago. Above this layer is modern soil. You might wonder why the rocks just under the soil are so old. Where are all the rocks that were deposited in last 400 million years? Why aren't there any 70 million year old dinosaur bones here? The answer to this riddle of the missing rocks is the awesome power of glaciers. From 45,000 to 12,000 years ago glaciers advanced and retreated many times over the Minnesota landscape. These massive sheets of ice acted like bulldozers, scraping off hundreds of feet of younger rocks and grinding them into dust. Of course, this much ice would create a LOT of water when it melted. In fact, all of our modern river systems were shaped by this melted ice water.

Twelve thousand years ago the Mississippi River was a small tributary river to Glacial River Warren, a much larger glacial river to the south (now known as the Minnesota River). These rivers, swollen with water from the melting glacier, cut deeply into the ancient rocks. The soft St. Peter Sandstone yielded easily to the rushing waters, but the hard fossil-filled Platteville Limestone capping it was more resistant. In time a waterfall formed, the only natural falls on the entire Mississippi River. Over thousands of years this falls gradually moved almost 10 miles upstream as the hard limestone slowly gave way, a few feet at a time, to the powerful river. The falls can be seen today near what is now downtown Minneapolis, but the falls that you see today is very different from the falls whose soft splashing lulled the pioneers to sleep. The requested video is no longer available.

Although the Native Americans had long known and revered the falls, the name "Saint Anthony Falls" was given by the earliest pioneers that settled in the area that would become Minneapolis. Almost immediately, flour mills were built to harness this hydraulic power source and people poured into the growing city to work. The city was growing so fast that the slow, but constant, progress of erosion inching the falls further upstream almost went unnoticed. But by the late 1800's scientists realized that the hard limestone that created the falls was getting thinner and that without reinforcement their power source would disappear entirely. To protect the falls and the mills that depended on them, the once natural falls became the man-made timber and concrete structure that you can see today. Although you can no longer see the rocks that form Saint Anthony Falls at the actual falls itself, there are a number of places along the corridor to see and touch the rocks and geologic processes which created these falls. Sites of Geologic Interest

|

Last updated: February 15, 2025