|

Return to River of History. Discovery and Dispossession

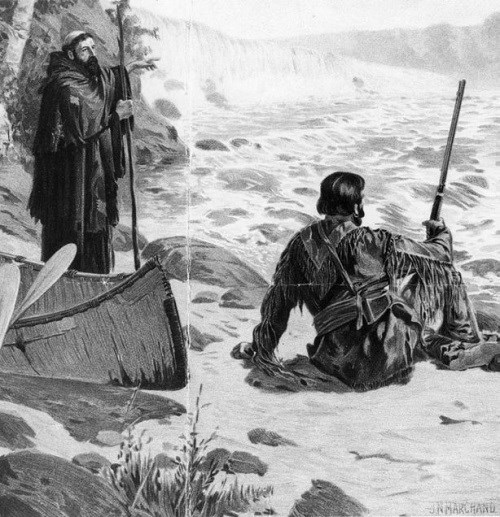

Artist: J. N. Marchand. Minnesota Historical Society To French explorers and traders probing westward from eastern Canada in the early 1500s, rumors of a great river stirred fantasies that only the unknown can evoke. Was it the Northwest Passage, that long hoped for shortcut to the riches of China? They knew that whoever found that fabled passage would gain enduring fame and wealth. To talk of the Mississippi River’s discovery, however, is an ethnocentric endeavor. To the Dakota and other Native Americans, the great river was as well known as a local freeway to an urban commuter. It was their daily and seasonal highway. But it was more. It was their front and back yards. It was their supermarket as well as their superhighway. They fished, hunted, gathered plants, planted crops, swam, and prayed in or near the river. The contrast between European discovery and Native American familiarity could not have been greater. The stories of European discovery lay bare this contrast. Dakota life changed dramatically as French, British and American explorers and traders found the MNRRA corridor. Where the Dakota lived, what they hunted and ate, and the tools and other material objects they relied upon changed. They began the era as the region’s dominant people and ended it, in 1854, with a forced exodus away from the river they had known and used for so long. While the French and British left little evidence of their presence in the MNRRA corridor, the Americans took it over, transforming not only Dakota life but the river valley’s landscape and ecosystems. The FrenchDuring the French era, the Mississippi evolved from a rumor into a thoroughfare of exploration and Euro-Indian commerce. The French period on the upper Mississippi covers approximately 100 years, but the French presence was limited and sporadic. The French began exploring eastern Canada in the early 1500s. In 1534 Jacques Cartier sailed up the St. Lawrence to the site that would become Montreal. But the French only established small fishing camps and trading sites. Samuel de Champlain finally founded a settlement at Quebec in 1603-04, and the French began sending traders and explorers into the continent’s depths. In 1623 or 1624, Etienne Brule became the first to report on rumors of a vast lake (Lake Superior) to the far west. Ten years later, in 1634, Jean Nicolet voyaged into Green Bay, contacting the Winnebago, or Ho-Chunk. And in 1641, Recollet priests Charles Raymbault and Isaac Jogues became the first to document the discovery of Lake Superior. They met the Saulteurs, or Chippewa, and reported on news of the Dakota, who lived on a great river, only 18 days away. These are the recorded accounts. The coureur de bois (independent, illegal fur traders, who ranged in advance of the official explorers and legal traders) may have visited the Great Lakes, the Dakota and the Mississippi earlier, but we may never know.1 Medard Chouart, Sieur des Groseilliers, and Pierre d’Espirit, Sieur de Radisson, might have been the first Europeans to see the upper Mississippi. Between 1654 and 1660 they conducted fur trading expeditions into the western Great Lakes and supposedly beyond. On at least one voyage, they purportedly canoed into Green Bay and up the Fox River. They then crossed over a short portage and into the Wisconsin River and paddled down to the Mississippi River. This route–the Fox-Wisconsin waterway–would become one of the principal highways of exploration and trade. Groseilliers and Radisson possibly traveled upriver as far as Prairie Island. The evidence is sketchy, and Minnesota historian William Watts Folwell calls it too far fetched to give Radisson and Groseilliers the title of the river’s European discoverers.2 By the 1670s, the French were poised to explore the Mississippi River. They had posts as far west as La Pointe, on Madeline Island, in Chequamegon Bay. Rumors of the “Mechassipi” or “Micissipi” grew and inflamed the hope that it was the Northwest Passage. Jean Talon, the indendant or head of finance, commerce and justice, in New France, chose Louis Joliet and Father Jacques Marquette to lead an expedition to the far-off river. On May 17, 1673, they left Michilimackinac, near Sault Ste. Marie, took the Fox-Wisconsin waterway, and glided into the Mississippi on June 17, 1673, becoming the first Europeans to unques- tionably discover the river. From here the party drifted south, hoping to find the river’s mouth. After a month they decided that the river flowed into the Gulf of Mexico. Fearing the Spanish and Native American tribes, they turned around and headed back to the Illinois River. Traveling up the Illinois, they crossed into Lake Michigan. Although the French had discovered the upper Mississippi River, the reach above the Wisconsin River’s mouth lay unexplored. Joliet’s account and France’s desire to expand its claim to America, to capture the trade, and to find the route to the Far East, however, spurred the French government to want more detailed information about the river and its inhabitants.3 Meanwhile, du Luth, itching to reach the Mississippi and the Dakota, left his post on Lake Superior, near Thunder Bay, crossed over the continental divide, and canoed down the St. Croix River. At the St. Croix’s mouth, he heard rumors of some Europeans who had passed downriver shortly ahead of him. Fearing they could be English or Spanish, expecting they might be French, he took a canoe and pursued them. On July 25, 1680, he found the French and Dakota paddling upriver and “rescued” Hennepin’s party. Together they continued on to Mille Lacs, where they arrived on August 14. On this trip, the Dakota traveled up the river to St. Anthony, portaged around the falls and continued up the Mississippi and Rum Rivers. Late in September, the Frenchmen finally returned east. Since they left in canoes and took the Fox-Wisconsin route, they probably went down the Mississippi through the MNRRA corridor again.7 The British, 1763-1815The British did not immediately fill the political vacuum created by their victory over the French, but no economic vacuum occurred. French and Spanish traders continued to frequent the area, the French coming up from New Orleans and the Spanish from St. Louis. When the British did enter the fur trade of the upper Mississippi River valley and the western Great Lakes, they tried a different system. Rather than sending traders to the tribes, they expected the tribes to come to them at posts like Michilimackinac, which was at the border of Lakes Michigan and Huron. The policy failed. In 1767 the British granted licenses to traders and let them rush into the interior, setting off rampant competition. By the 1780s many English traders worked among the Dakota. No evidence exists, however, that the French, Spanish or English established posts in the MNRRA corridor during the British era. Prairie du Chien was the primary trading place on the upper Mississippi. Not only did various tribes meet French, Spanish and British traders there, the traders fanned out from the wilderness entrepot. British and French traders canoed the MNRRA corridor regularly to trade with the Dakota and Chippewa.20

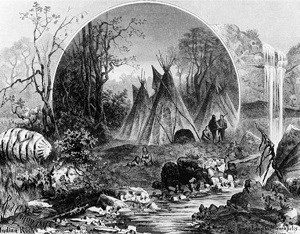

Theodore H. Lewis, The Northwest Archaeological Survey, 1898. Carver expands our knowledge of Dakota social and cultural traditions within the MNRRA corridor. On November 14, he came to “the great stone cave calld by the Naudowessee,” he said, “Waukon Tebee, or in English the house of spirits.” The cave would take Carver’s name. Carver “discovered” something already old to the Dakota. He found “many strange hieroglphycks cut in the stone some of which was very a[n]cient and grown over with moss.” (Figure 4) Like a graffiti vandal, he etched the king of England’s coat of arms among the Native American characters. From the cave, Carver headed up to St. Anthony Falls on the 15th. After visiting the falls, Carver returned downstream and canoed up the Minnesota River where he camped with the Dakota for the winter.23

The following April, Carver heard about “an annual council” to be held near the cave he had visited. The chiefs of several bands planned to attend. Such a meeting would provide Carver the opportunity to harangue the Dakota to go to the British and to stop trading with the French. So on April 26, 1767, he left what he termed the “Grand Encampment” of the Dakota on the Minnesota River and traveled down to the Mississippi, where he arrived on April 30. The next day he met the Dakota near the cave, possibly at or near a village that would become Kaposia, and got himself invited to the council. Eight bands attended.24

The hereditary chief of the Mottobauntowha band (possibly Wabasha I) presided at the conference. The chief addressed the advantages and disadvantages of going to the French and British. His people feared disease if they traveled to the French in Louisiana, although at least one chief still favored the trip (although the French usually came to the Dakota). Carver comments that while the Native Americans were “great travelers,” few were willing to make the journey to Michilimackinac. The chief encouraged Carver to return again with more traders to bring them guns, powder, tobacco and other goods. The Dakota especially wanted guns for war.25

Intertribal warfare intensified during the British era, as the Chippewa expanded farther south and west into Minnesota, as the Dakota became more well armed, and as fur animals and game supplies dwindled. Prior to entering the council, Carver had learned that an Iroquois man, whom he had employed as an interpreter the previous fall, had joined a band of Chippewa that had stolen down to the Mississippi to attack the Dakota.26 By the 1790s the Dakota and the Chippewa fought along the Mississippi River from St. Anthony Falls to Prairie du Chien so intensely that one British trader claimed few Indians came to the area.27

Peter Pond, another British adventurer to leave an account during this era, had less grandiose goals than Carver. He simply wanted to bring out as many furs as he could. In 1773, Pond shows, fur traders had established themselves throughout the upper Mississippi River region and especially among the Dakota of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers. Upon arriving at Prairie du Chien, Pond found “a Larg number of french & Indans Makeing out thare arangements for the InSewing winter and Sending of thare canues to Differant Parts Like wise Giveing Creadets to the Indans who ware all to Randavese thare in Spring.” Pond had nine traders that he sent to different places, including two that he accompanied up the Minnesota River in October. During the winter, he traded with the Dakota who visited him and noted that he had a French competitor nearby who had been trading with the Dakota for several years. Although Pond does not indicate that traders wintered or bartered within the MNRRA corridor, he demonstrates that numerous British and French traders had infiltrated the Dakota lands. At a minimum, he shows, traders traveled on the Mississippi through the corridor to reach bands on the Minnesota River and to get to the Chippewa at the Headwaters.28 After returning to Michilimackinac, Pond learned that the conflict between the Dakota and Chippewa had worsened. Fearing that the trade would collapse, the British sent their traders out with wampum belts to bring as many chiefs to Michilimackinac as possible. In 1775, after another year of trading on the Minnesota River, Pond headed back to the British entrepot bringing eleven Dakota chiefs with him for the treaty negotiations. At the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi, a delegation from the Chippewa, accompanied by traders who had spent the winter near the Headwaters, startled Pond’s party. Given the recent battles, Pond recalled, “I was Much Surprised to Sea them So Ventursum among the Peaple I had with me, for the Blad [blood] was Scairs Cald the Wound was yet fresh.” The two parties then proceeded together to Michilimackinac, somehow avoiding serious conflict. Hoping to end the intertribal war and ensure their profits, the British tried to convince the Dakota and Chippewa to make the Mississippi River the fixed boundary between the two tribes. The traders succeeded in getting the Dakota to agree not to cross the Mississippi to the east and the Chippewa not to go to the west. The attempt to create a dividing line between the Chippewa and Dakota failed, however. Despite their statements at Michilimackinac, the Dakota still viewed some lands east of the Mississippi as theirs.29

British sovereignty (ignoring Dakota claims) over the eastern MNRRA corridor technically ended with the Treaty of Paris, in 1783, that concluded the American Revolution. By that treaty, United States now owned the land to the east of the Mississippi. The Spanish still claimed the land west of the river. In reality, British traders continued to dominate the fur trade in the region and with it the politics and economy. British traders, especially those of the Northwest Company (established in 1787), continued building posts in Minnesota and Wisconsin, including sites at Grand Portage, Fond du Lac (at the mouth of the St. Louis River), Prairie du Chien, Sandy Lake and Leech Lake.30

The only official American effort to establish its presence came after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, by which America gained control over an 825,000,000-square-mile tract west of the Mississippi from France for $15,000,000. (France had reacquired Louisiana from Spain three years before.) General James Wilkinson, determined to eliminate the British influence in the region, dispatched Zebulon Pike up the Mississippi from St. Louis to the river’s headwaters (Figure 5). Wilkinson ordered Pike to choose the best sites for military posts and obtain the land for them from the Native Americans. He also directed Pike to prepare the way for government trading posts, make alliances with the Chippewa and Dakota, stop intertribal fighting, and locate the Mississippi’s source.31

Pike left St. Louis on August 9, 1805. As he proceeded up the Mississippi River, he found an active and thriving fur trade. At Prairie du Chien he picked up James Fraser, a trader who was planning to winter with the Dakota bands on the Minnesota River. At Lake Pepin, another trader, Murdoch Cameron, joined Pike’s expedition. Cameron also planned to trade with the Dakota on the Minnesota River. When they reached the St. Croix River, on September 19, Fraser and Cameron begged leave to undertake some business in the area and departed. Three miles below the mouth of the Minnesota River, Pike came upon a “Mr. Ferrebault’s” (Jean Baptiste Faribault) camp. The trader’s piroque had been damaged, forcing him to stop. There is no indication that Faribault made this camp a trading site or if, as had happened to Pike many times already, he had laid up to fix his boat.32

Artist: Charles Wilson Peale. Independence National Historic Park. On September 21, Pike reached Kaposia, where he had breakfast. He counted 11 lodges but the band was out collecting “fols avoin,” or wild rice. Two miles farther up, he met a small Dakota camp of four lodges. Whether this was a separate village or a temporary camp is not clear. When Pike reached the large island at the Minnesota’s mouth that bears his name, he set up camp on the island’s northeast point and waited for the Dakota.33 He did not wait long. The next day Petit Corbeau or Little Crow and about 150 of the band’s warriors arrived. Later that day Pike went up the Minnesota River to the Dakota village where Cameron had his post. While the Dakota warriors had left, they had returned upon hearing of Pike’s arrival. The following day, at noon, Pike began negotiating with seven Dakota chiefs at Pike Island. He wanted Dakota lands at the mouths of the St. Croix and Minnesota Rivers. Although only two Dakota leaders signed, Little Crow and Le Fils de Pinchow or Pinichon, the cession would become fact. The Dakota gave up some 100,000 acres for which the Senate initially agreed to pay only $2,000.34 Unlike Carver and Pond, Pike delivers some insights about the river itself in the MNRRA corridor. After passing the St. Croix’s mouth on his journey upstream, Pike remarked that the river became surprisingly narrow. To emphasize the point, he tested how many strokes he need to cross in his bateau. It took only 40. And, he wrote, “The water of the Mississippi, since we passed Lake Pepin has been remarkably red; and where it is deep, appears as black as ink. The waters of the St. Croix and St. Peters (Minnesota), appear blue and clear, for a considerable distance below their confluence.”35 Pike offers rare details about the river above St. Anthony Falls. On October 1, after portaging around St. Anthony Falls, Pike initially found the river deep enough. Within four miles, however, the river became shallow, and his party struggled for the rest of the day, having to fight their way over three rapids. The next day the Mississippi became so difficult Pike claimed that anyone less determined would have turned back. His party passed some large islands and more rapids. For much of the day they waded in freezing cold water, “to force the boats off shoals, and draw them through rapids.” The river winds only some 25 miles from St. Anthony Falls to the Crow River’s mouth. For Pike’s crew, it seemed an interminable distance. They did not reach the Crow River until October 4.36 Like the British traders and explorers, Pike found intertribal warfare rampant and hoped to end it. Only his arrival had stopped the Mdewakantons living up the Minnesota River from going to war. Upon reaching the Crow River, he found one reason why the Dakota had probably set off to attack the Chippewa. On October 4, Pike recorded that “Opposite the mouth of Crow river we found a bark canoe, cut to pieces with tomahawks and the paddles broken on shore; a short distance higher up, we saw five more; and continued to see the wrecks, until we found eight.” Pike’s interpreter recognized the canoes as Dakota and some broken arrows as Chippewa. The Chippewa had carved marks on the paddles, indicating the number of men and women they had killed. On his return trip down the Mississippi, Pike hoped to convince the Dakota to make peace with the Chippewa. So on April 11, when he again reached Pike Island, he sent for the Dakota chiefs. Le Fils de Pinchow came soon after and agreed to host a council. At sunset, the Dakota called Pike to Le Fils de Pinchow’s village, about nine miles up the Minnesota. Pike found some 40 Dakota chiefs waiting. They represented the Mdewakantons, Sissetons and Wahpetons. The Dakota numbered about 100 lodges or 600 people. As this was the same time of year that Carver had attended a great annual Dakota conference in 1766, Pike may have arrived at the time of another annual meeting. “The council house,” Pike recorded, “was two large lodges, capable of containing 300 men. In the upper were 40 chiefs, and as many pipes, set against poles; . . .” Pike placed some Chippewa pipes that he had acquired next to the Dakota pipes as a gesture of his desire to establish peace between the tribes. Pike apparently had little effect. The next day as he headed back down the Minnesota River, some Dakota from a number of lodges about three miles above the mouth hailed him. Although they initially received him well, the Dakota forcefully let him know they intended to go to war.37 Pike’s expedition signaled a new era. His was the first of an increasing number of missions to establish America’s political and economic control over the upper Mississippi. But for now, the British and French traders remained active on the upper river. Demonstrating how much activity he found on the Mississippi River below St. Anthony Falls, Pike regarded the falls as the gateway to the wilderness beyond. On September 27, he penned a letter to his wife and prepared a package for his commander in St. Louis. “This business, closing and sealing,” he remarked, “appeared like the last adieu to the civilized world.”38 On April 10, on his return trip, he commented again on this feeling. “How different my sensations now,” he confessed, following with a long description about how bleak the expedition’s outlook and condition had been when they had passed earlier. They had been tired, cold, sick, and “just upon the borders and the haunts of civilized men, about to launch into an unknown wilderness; . . . ”39 While that wilderness may have been unknown to Pike and the Americans, it would not be for long. Pike’s influence was short-lived, as America failed to follow up until after the War of 1812. The growing American presence did disrupt the flow of trade goods to the Native Americans in the MNRRA corridor and throughout the region. As tensions between the United States and Britain mounted, President Thomas Jefferson embargoed all commerce in the fall of 1807. The United States actively tried to stop British traders from delivering goods to and collecting furs from Indians in the western Great Lakes and upper Mississippi River valley. This move forced some British traders to withdraw.40 As the Americans limited the supply of goods reaching the Dakota and as American traders failed to make up the difference, the Dakota began to suffer. The War of 1812 led to even greater shortages of goods and, according to Anderson, left the Dakota impoverished. Because the English traders had married Dakota women and had had children by them, and because the British made an effort to keep trade open, the Dakota sided with the British during the war. Only with the Treaty of Ghent, in 1815, which ended the war, did the British traders begin to withdraw.41 By the end of the British era in 1815, we know much more about the MNRRA corridor. While some aspects of Dakota lifeways had changed little, the Dakota were undergoing an important transition.42 The Mdewakanton villages still had about 4,000 to 5,000 people–close to the numbers they held 20 years earlier. Important changes had occurred, however. On both his trips to trade with the Dakota on the Minnesota River, Pond commented on the abundance of game along the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers. He killed deer, buffalo, ducks, geese and other animals with little effort.43 By the end of the British era, over- hunting and the depletion of fur and game animals forced the Mdewakantons to break into smaller groups and to begin thinking about agriculture. As early as 1775, Pond noted, the Dakota living near the mouth of the Minnesota River raised “Plentey of Corn. . . .”44 At Kaposia, Pike discovered the Mdewakantons living in bark lodges, which Anderson suggests indicated a change in subsistence pattern to rely more on corn and beans. Anderson also argues that “changing economic conditions had broken up the larger villages seen by earlier travelers, and this had affected tribal unity.”45 Assuming Carver’s and Pond’s accounts are somewhat true, they capture many of the particulars we know characterized the British period. The Dakota had moved out of their traditional homeland around Mille Lacs Lake. They had settled on the Mississippi in the MNRRA corridor and downstream and up the Minnesota River. The MNRRA corridor had become increasingly important to the Dakota. Carver, Pond, and others found the Mdewakantons and other Dakota bands holding regular councils within the corridor or just up the Minnesota River. And the Kaposia band had established a seasonal village on the Mississippi above the St. Croix’s mouth. The area had gained more than seasonal importance to the Kaposia band, as the burial of band members near the village demonstrated. One of the most obvious changes was the extent to which European and American products had begun replacing native goods. Although the supply was never steady and full, the Dakota grew more dependent upon foreign manufactures. Guns had become essential for successful warfare, and warfare, as a result of the fur trade, was becoming more frequent and deadly. While still an independent people, the Dakota would look more often to outsiders for the tools of their existence, and they would increasingly deplete their natural resources to get them. The AmericansAmerican explorers and traders dispersed through the upper Mississippi River valley following the Treaty of Ghent in 1815, which codified the American victory. Only eight years after the treaty, the Virginia, the first steamboat to navigate the upper Mississippi River, reached the first permanent military post in the area. Steamboats hurried exploration, trade and settlement, and they hurried change for the Dakota and the river. The era of exploration would end and the era of settlement begin during these 25 years, although it would be decades before Americans knew the land as well as the native inhabitants had. As the number of Americans swelled, they would squeeze the Dakota into a smaller and smaller area, forcing more changes in their lifestyle and, before long, forcing them away from the Mississippi River and the MNRRA corridor. As game and fur bearing animals disappeared, upsetting the ecosystems of the river and its watershed, the Dakota would turn to agriculture and annuities from the American government, further undermining their traditional ways. Following the War of 1812, the American Fur Co., under John Jacob Astor, bought the Northwest Company’s posts in the United States and began asserting control over the fur trade. In an attempt to eliminate foreign traders, Astor convinced Congress to pass the Foreign Intercourse Act of 1816, which required foreign traders to become naturalized or leave. The Americans, however, had to enforce the act.46 Despite the American victory and ignoring the new act, some British traders remained on the upper Mississippi. But this time the Americans had come to stay, and in 1816 they began building forts at Prairie du Chien and Green Bay. As the Mdewakantons had relied on, fought with, and married English traders, they did not readily accept the Americans. In 1816 Little Crow II (Cetanwakanmani) and Wabasha II traveled to the British post at Drummond Island, near Sault Ste. Marie, to learn how seriously they should take the Americans. The British commander answered: seriously. Little Crow and Wabasha quickly learned what he meant. They returned up the Fox River and down the Wisconsin, entering the Mississippi just below Prairie du Chien. When they tried to pass the frontier hub and camp above with the other Dakota already there, the American commander, Brevet Brigadier General Thomas A. Smith, refused to let them. Smith insisted that the two Mdewakanton leaders first had to renounce the British and recognize the Americans as their new sovereigns. Little Crow and Wabasha conceded, giving up their British flags and medals. But British traders continued to reach the eastern Dakota, and the Americans felt a growing need to drive the British out.47

Artist: Charles Vincent Peale. Independence Hall Collection, Philadelphia. So in 1817, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun sent Stephen H. Long, a Topographical Engineer (a branch of the army that had split temporarily from the Corps of Engineers), to map the upper Mississippi and locate potential military sites (Figure 6). On July 15, 1817, Long reached the mouth of the St. Croix River. His description of the Mississippi beyond this point provides more information about the MNRRA corridor than had been left by the uncounted traders who had been through it so many times. Four miles above the St. Croix’s mouth–an area now made wide by the pool behind Lock and Dam 2–Long said was the narrowest place below St. Anthony Falls. As he measured it, the river was only 100 to 120 yards wide. Since Pike had crossed the river nearby in 40 strokes, Long decided to see if he could beat him. Although Pike’s bateau may have been much more clumsy than Long’s six-oared skiff, Long needed only 16 strokes.48 Shortly after passing this narrow gap, Long commented that his party had “Passed the Detour de Pin or Pine Turn of the Mississippi (Pine Bend), which is the most westwardly turn of the river, between St. Louis and the Falls of St. Anthony.”49 It was only nine miles to the Minnesota River overland, he observed, but two days by boat. Delaying him further, Long complained that the twisting river made using their sail nearly impossible. On Long’s second expedition up the Mississippi, in 1823, William H. Keating, the expedition’s journalist, grumbled that the river up to St. Paul was “crooked and its channel impeded by sandbars; and the current rapid, so that the progress of the boat was slow.”50 Long provides the first comment on the river’s water quality. Long recorded, during his 1817 trip, that “The Mississippi above the St. Croix emphatically deserves the name it has acquired, which originally implies, Clear River. The water is entirely colorless and free from everything that would render it impure, either to the sight or taste. It has a greenish appearance, occasioned by reflections from the bottom, but when taken into a vessel is perfectly clear.” While Mississippi more accurately means “great river,” Long presents a stream dramatically different from the one choked with pollution and sediment at the end of the century. Like Pike, Long noted the water’s reddish appearance below the mouth of the St. Croix.51 On July 16, 1817, Long’s party passed Kaposia, which held 14 lodges (three more than Pike had counted 12 years earlier), and its nearby burial ground. Demonstrating that the Chippewa had not forced the Mdewakantons out of the St. Croix valley yet, most of Little Crow’s people were hunting up that river when Long passed. Given how narrow the river was here, Long noted that the village commanded the river and all who tried to pass. Little Crow’s people, he remarked, used their strategic position to exact tolls from traders.52 Long also arrived at Carver’s Cave that day but was unimpressed. While the cave had once contained Native American etchings and a small lake, Long found that the cave had collapsed in many places and was filling with sand. He records no markings by anyone in his 1817 account.53 During the 1823 voyage, Keating reports that they found the names of Henry R. Schoolcraft and the party of Lewis Cass, the Michigan Territorial Governor, carved into the sandstone inside. Cass and Schoolcraft had visited the cave in 1820.54 Pike was much more impressed with Fountain Cave, which lay some three miles above Carver’s Cave and a few miles below the Minnesota River’s mouth. Long observed that “The entrance of the Cave is a large windinding [wind-ing] hall, about 150 feet in length 15 feet in width & from 8 to 16 in height, finely arched over head & walled on both sides by cliffs of sandstone nearly perpendicular. Next succeeds a narrow passage & difficult of entrance which opens into a most beautiful circular room, finely arched above and about 50 feet in diameter. The cavern then continues a meandering course, expanding occasionally into small rooms of a circular form.” Long also recorded that a clear stream flowed through the cave “& cheers the lonesome dark retreat with its enlivening murmurs.” Fountain Cave, Long says, had been discovered recently, and the Mdewakantons had learned of it about six years earlier. The cave would become a popular nineteenth-century attraction.55

Artist: Henry Inman. Minnesota Historical Society. While Long examined the sites acquired by Pike and recommended that the United States build a fort at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, he did not try to impress the Dakota with the Americans’ growing might in the region. An Indian agent named Benjamin O’Fallon initially assumed this role. In the spring of 1818, O’Fallon took a detachment of 50 U.S. soldiers up the Mississippi River in two armed keelboats. He stopped at the Mississippi Mdewakanton villages and continued 30 miles up the Minnesota to Shakopee’s village. This was the largest U.S. expedition into Dakota territory and helped convince the Dakota to abandon any hope the British might return.56 Little Crow’s actions made it clear that the United States still needed to make this point. When O’Fallon arrived at Little Crow’s village, the chief was absent, having gone to visit and protect British traders in western Minnesota (Figure 7).57

Artist: Henry Lewis. Minnesota Historical Society. In August 1820 Colonel Josiah Snelling replaced Leavenworth, and on September 10, Snelling set the fort’s cornerstone. After visiting the nearly completed fort in 1824, Major General Winfield Scott recommended that the fort’s name be changed from Fort St. Anthony to Fort Snelling (Figure 8). The following year, the War Department agreed.59 Fort Snelling quickly became the regional center for intertribal gatherings and negotiations. In addition to the Dakota, the Chippewa, Menominee, and Winnebago visited the fort. As Forsyth promised, the fort became a trade center, as traders located across the river at Mendota and nearby at Camp Coldwater.60 By the 1820s the Dakota participated in an economic system that would undermine their traditional culture. The more they relied on European and then American trade goods and food, the more they hunted to acquire the furs to trade. By the 1820s beaver were scarce, and the Dakota turned to muskrats. Muskrat skins brought far less than beaver pelts, so the Dakota had to capture many more muskrats. Muskrats totaled three-fourths of the furs trapped by the Dakota during the 1820s, and by the mid-1830s, they accounted for some 95 percent. The destruction of game and fur-bearing animals east of the Mississippi and the focus on the muskrat and other small animals for food and furs forced the Mdewakantons to hunt farther west.61 Keating, in his account of Stephen Long’s 1823 expedition, reported that game was rapidly disappearing. He found little game along a 200-mile reach of the Mississippi River below St. Paul. Buffalo no longer drank from or wallowed in the Mississippi. Long had encountered a few buffalo near the Buffalo River (Beef Slough), just below Lake Pepin, during his 1817 expedition.62 As more American traders moved into Dakota lands, competition among the traders encouraged even greater destruction of fur and game resources.63 During the 1820s, forces introduced by the fur trade and the growing American presence began to tear at Dakota community life. More traders and steamboat transportation meant that American and European goods became abundant, replacing ever more native articles. Faced by growing competition, traders relied more on alcohol, and alcoholism became rampant. At Kaposia factionalism intensified. Little Crow, himself prone to excessive drinking, could not hold the village together. Grand Partisan and Medicine Bottle left to create their own villages after 1825. Grand Partisan established a village at “Pine Turn” or Pine Bend about eight miles south of Kaposia, and Medicine Bottle selected the west end of Grey Cloud Island for his. Even American efforts to stop intertribal warfare, which had been a traditional way for men to gain status, undermined the Dakota way of life.64 The depletion of game and the focus on muskrats also brought changes to the Dakota settlement and economic patterns. While the Mdewakantons still hunted along the Chippewa, St. Croix, Sauk and Crow Wing Rivers, they had less and less success each year. At Black Dog’s village, just up the Minnesota River from Fort Snelling, the Mdewakantons broke into small groups to hunt muskrats. Small groups worked more efficiently (suggesting a similar pattern for Little Crow’s people). By the mid-1830s, Dakota families began leaving their villages on the Mississippi to hunt muskrats on the Minnesota River and its tributaries. Little Crow IV, Taoyateduta, and the man who would assume his grandfather’s name and role, even left for the prairies. By the end of the 1820s and early 1830s, survival for the Mdewakantons who stayed in their villages became difficult. The demise of the region’s fur and game resources forced the Dakota, especially the Mdewakantons, to experiment more with agriculture. The small number living around the fort increasingly relied on handouts.65 William Clark, the superintendent for Indian Affairs, captured the plight of the Dakota hunter well. “‘This period,’” he wrote in 1826, “‘is that in which he ceases to be a hunter, from the extinction of game, and before he gets the means of living, from the produce of flocks and agriculture.’”66 By 1836 the Mdewakantons faced a crisis. Their numbers had fallen to about 1,400, as starvation, a smallpox epidemic, and warfare sapped their population. Thinking he could stop the downward spiral, Lawrence Taliaferro, the Indian agent at Fort Snelling, suggested that the Dakota sell their lands east of the Mississippi River. Although settlers were not pressing for the land, Taliaferro thought the Dakota could benefit far more from its sale than its use. He hoped the money would encourage the Mdewakantons to take up agriculture. Already Little Crow, Black Dog and Cloud Man had asked Taliaferro to help their people learn farming. Cloud Man’s people planted crops at Lake Calhoun in 1830, establishing a community named Eatonville, after John Eaton, the Secretary of War. By 1834, 135 Dakota lived at Eatonville. The U.S. government initially balked at Taliaferro’s treaty proposal. But when Congress created the Wisconsin Territory in August 1836, the government endorsed the idea.67 By the end of September 1837, the treaty’s details had been worked out and the Dakota had agreed to them. Under the treaty, the Mdewakantons were to receive $25,000 in food, farm tools, and goods annually for 20 years. They were also to get a permanent $15,000 annual annuity that represented the interest on a $300,000 trust fund. Congress did not officially approve the treaty until June 15, 1838.68 The payments from the 1837 treaty gave the Mdewakantons a brief respite. As the annuities provided another food source and as more tribal members received smallpox vaccinations, their population began to recover. On the treaty’s eve, the Mdewakanton population had stood at about 1,400. By 1850 it reached 2,250 individuals, a 60-percent surge. (Granted, members returning from the west boosted the band’s numbers.) Ironically, Anderson contends, the treaty allowed the Dakota to continue their nomadic lifestyle, by making up for the declining success of the hunt.

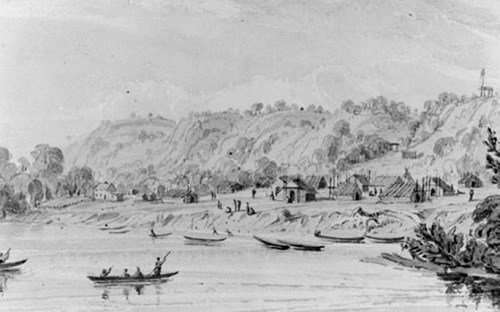

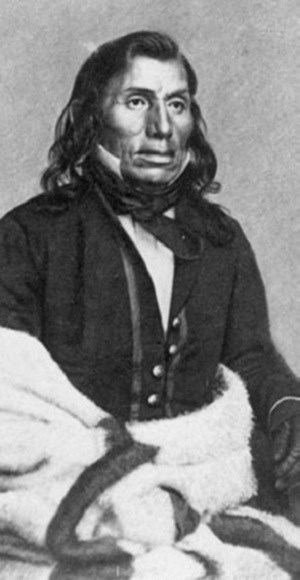

Artist: Seth Eastman. Minnesota Historical Society. The annuities could not hide the demise of the Dakota’s game and fur resources. By the late 1830s, muskrat prices had fallen so low in the East that some traders quit taking them. Outside the annuities, muskrats furnished most of the Dakota’s income, allowing them to buy food and trade goods. Without muskrats, the Mdewakantons depended more upon the annuities and the Americans. This dependence deepened as game disappeared and pork and flour replaced wild meat and wild rice. And the Dakota, although they had begun experimenting with agriculture, were far from becoming sedentary.69 As the Mdewakantons and other Dakota relied more upon the Americans, the Americans steadily pushed onto the Mdewakanton’s lands. By 1838 Little Crow had moved Kaposia across the Mississippi River (Figure 9). Almost immediately settlers, including the whiskey seller Pierre “Pigs Eye” Parrant, claimed the land at the old village site. Parrant had built a cabin at Fountain Cave on June 1, 1838, but Fort Snelling’s commandant kicked Parrant and others off the military reservation later that year. Parrant then settled at or near the old Kaposia village. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, the American population east of the river steadily increased, and Methodist missionaries opened a school near Kaposia shortly after the 1837 treaty.70 The river was supposed to have been a boundary, but American settlers started crossing over by the hundreds to squat on lands they believed the Federal Government would inevitably open to settlement. Some hoped to capture the waterpower on the west side of St. Anthony Falls (like some entrepreneurs had already done on the east after the 1837 treaty). Others simply wanted to stake their claim to farms, knowing they could get the land as cheap as possible. Pressure began mounting for the Dakota to sign another treaty, one that would bring an end to their residence along the Mississippi River and lower Minnesota River. This time the Americans would force the treaty on the Dakota. After Wisconsin became a state in 1848 and Congress created the Minnesota Territory in 1849, talk of removing the Dakota intensified. Within a couple of years St. Paul had 142 buildings (Figure 10). Pig’s Eye–the old Kaposia village–had about a dozen farms, and two frame houses stood at the new Kaposia (Figure 11). St. Paul’s expansion and the Dakota’s growing dependence upon the Americans made another treaty inevitable.71 While the western bands, the Sissetons and Wahpetons, wanted a treaty so they could get annuities, the Mdewakantons were not so anxious. The Mdewakantons knew they would be giving up their homeland on the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. But they, like the other bands, were becoming desperate. On July 18, 1851, the United States, under a commission headed by Alexander Ramsey, the territorial governor, began negotiating with the western, or upper bands, of the Dakota. Despite some initial troubles, the Sissetons and Wahpetons signed the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux on July 23. This put the Wahpekutes and Mdewakantons in the middle of lands ceded to the United States and intensified the pressure on both bands to sign a treaty.72 On July 29 the Mdewakantons and the Wahpekutes began negotiating with Governor Ramsey and the U.S. treaty commission, in a warehouse at Mendota. Ramsey addressed the Dakota frankly: “‘You would not only have the whites along the river in front but all around you, . . . You should pass away from the river and go farther west.’”73 Wabasha III and the other chiefs balked. The United States had failed to comply with provisions of the 1837 treaty, and the Dakota insisted these be met before continuing. At Wabasha’s (III) request, the council moved outside to Pilot Knob, above the Minnesota River, in full view of the land and rivers that had been so important to them for so long (Figure 11).74 Wabasha then warned everyone that some Mdewakantons had threatened to kill any chief who signed the treaty. Nevertheless, on August 5, Little Crow (IV or Taoyateduta) stood up for the Mdewakantons and signed (Figure 12). Thirty-five other leaders followed. With this event, Little Crow assumed leadership of the Mdewakantons and acknowledged that his people would have to leave their homeland.75 Under the Treaty of Mendota, as it became called, the Mdewakantons and Wahpekutes were to receive a 20-mile-wide reservation on the Minnesota River in return for their land. The government also promised goods and services worth $1.41 million. Of this, $1.16 million was to go into a trust fund for 50 years. The government would pay 5 percent ($58,000) of this annually to the bands as food, acculturation projects and cash ($30,000).76 The Treaties of Mendota and Traverse des Sioux signaled the explosion of American settlement around the Mississippi River in the Twin Cities metropolitan area. Settlers in the Minnesota Territory celebrated the two treaties. Many hurried west across the river at the news of the Mendota treaty and staked claims to farms and townsites, before the Senate ratified it. The Mdewakantons complained. The government had not made any payments promised by the treaty. The commandant at Fort Snelling referred the matter to Washington and nothing came of it. While the Mdewakantons resented the settlers, they relied on them for handouts, when they returned from their winter hunt.77

Indian face is painted into the waterfall at Fawn’s Leap, a waterfall that lay just below St. Anthony. The face may suggest something the spiritual. Artist: Rudolph Cronau, 1881. Minnesota Historical Society. The Senate finally ratified both treaties but eliminated the provision for permanent reservations. The Dakota then questioned whether they should move. While the western bands agreed to the change, the Mdewakantons rejected it. On September 4, 1852, the band finally agreed to the amendments. Henry M. Rice, a St. Paul fur trader hired by Ramsey, apparently assured the Mdewakantons that they would get the reservation on the upper Minnesota River that they wanted.78 The task of convincing the Dakota to leave their ancetral homes fell to Willis A. Gorman, who succeeded Alexander Ramsey as Minnesota’s territorial governor in 1853. In the spring of 1853, speculators and settlers surveyed Kaposia II for town lots and farms, usurping the Dakota’s fields. While Little Crow’s people did not overtly resist the intrusions, the Dakota at the villages under Black Dog, Wabasha, and Wakute (Red Wing) did and pressure on the Dakota to leave grew. Little Crow won a short reprieve from Gorman, however. The United States had agreed to prepare the reservation by planting fields and building warehouses, but failed to do so. Little Crow insisted that his people could not survive the winter without provisions and convinced Gorman to let the Mdewakantons stay on the Mississippi through the winter of 1853-54.

Photo by J. E. Whitney. Minnesota Historical Society. In the spring of 1854, Gorman took Little Crow to Washington, D.C., and introduced him to the Secretary of the Interior and President Franklin Pierce. Little Crow received enough assurances about the reservation to satisfy him, and he learned how futile resisting would be. In May 1854, Little Crow led his people on an exodus up the Minnesota River to the new reservation near Redwood. By the end of June, most of the Mdewakantons had reached their new home; only a few remained around the Mississippi River.79 Removing the Mdewakantons from the Mississippi River and the MNRRA corridor closed an important era in the river’s history, in Dakota history, and in the history of American settlement. For hundreds of years, the Dakota had used the river without changing it much, physically or ecologically. But under the fur trade, the Dakota began altering the river’s ecosystem, nearly eliminating some species. After the Dakota left, American settlers freely cut down the forests, plowed the ground, and fully harnessed the falls. As more Americans came and the more they relied on the river, the more they would want to change the river and the land to fit their needs. At this point the history of settlement takes over the story in the MNRRA corridor. Endnotes

|

Last updated: November 22, 2019