Park Ranger; seg. 1: Welcome to Mammoth Cave National Park, home of the world’s longest known cave system. With 412 mapped and explored miles of cave passage and numerous more passages awaiting exploration, no other single cave system comes close. On the surface, Mammoth Cave National Park encompasses almost 53,000 acres of lush forest, rocky outcrops, rivers, streams, and over 80 miles of hiking trails available for visitor use. The route we will be taking today will cover almost a mile of the “Historic” section of Mammoth Cave where we will travel through the passages that gave the cave its name, “Mammoth.”

Narrator; seg. 1: It’s a balmy 89 degrees outside, and the humidity hangs heavy in the air (sound: birds 31 sec). Fall is almost here, and the leaves are slowly beginning to fade from the green of summer to the amber hues of fall. We begin our tour of Mammoth Cave with Ranger Chris by walking down a 1/8-mile paved sloping path that was once the County road.

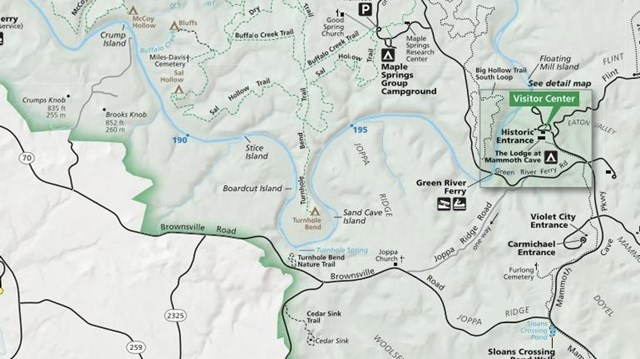

Park Ranger; seg. 2: As we descend the hill toward the cave entrance, you will notice rough, grainy, brown sandstone peeking out of the banks on each side of the trail. Nearing the cave entrance, we can see the stone transition to a smoother, gray limestone, a rock that makes up the vast majority of the cave’s interior. The Green River has spent its existence cutting its way downward through these rock layers and creating the hills and valleys around us. Locals once used this path to access a ferry that would shuttle them to what is now the north side of the National Park.

Narrator; seg. 2: Fallen leaves crunch beneath your feet. The sweet smell of blossoms and fall leaves fill the air (sound: crunching leaves 13 secs). Along the trail, late summer flowers are still in bloom, scattering bits of azure, indigo, gold and snow white along the lush green moss-covered limestone rocks exposed in the hillside. Nearby, there is a rustle in the limbs as a two playful grey squirrels chase each other in the low canopy of the trees. At the end of the road there is an old timber fence to the right of the trail leading you up four steps to a concrete landing. As you get closer to the landing, a cool breeze tickles across your feet. Searching the landscape gives no obvious answer as to where it is coming from but as you walk further onto the landing and step down four more steps, you move even closer to the brisk air. On each side of the landing there is a stone wall with dark green moss and white and orange algae growing on the undisturbed surfaces. The moss feels like thick, soft carpet beneath your touch. The top of the stone is barren of life where visitors and rangers have touched and walked along the surface. At the edge of the landing, the rock wall begins to twist downward into the earth to your right. Sixty-eight concrete stairs descend into the dark opening where gray limestone layers have peeled away, forming a gaping hole into the unknown depths of the subterranean world. This is the source of the frigid air. You stop here as Ranger Chris begins to address the tour group.

Ranger; seg. 3: We are now standing at the entrance to Mammoth Cave. This land was designated a National Park in 1941, over 30 years before we knew of its amazing length. This designation came about largely because of its unique place among America’s history. A history as diverse, layered, and complex as its passages. Around 5000 years ago, Late Archaic and Early Woodland Indians made their way into and through at least 14 miles of the cave. Their exploration, which would span more than 2000 years, was a testament to their bravery, curiosity and persistence and was lit only by the dull glow of a torch made from river cane; the same type that grows along the banks of the river today. We believe they stopped utilizing the cave around 2000 years ago and have no evidence that anyone else would enter until settlers moved into the area. Local legend says that around 1798 a young boy, John Houchins, was roaming these very hillsides in search of game to take home to his family. Armed with his father’s long rifle, John eyed a beast that today is no longer found within the national park. With a shaky hand, John raised his rifle and took aim at a large black bear. Staring down the barrel, he squeezed the trigger. BOOM! As the puff of smoke dissipated, the bear was gone. John caught sight of the animal once again. Wounded but alive, the bear ran down the hill and into a huge opening in the ground with John in pursuit. Stories, like that of John Houchins, have served to spark the curiosity and imagination of millions of people for over 200 years. As we travel through the cave today, I hope to share with you, more of the stories that paved the way for Mammoth Cave to become your 26th national park.

Narrator; seg. 3: You follow Ranger Chris down the damp stairs that travel into the cave. Cascading from the top of the entrance is a waterfall that has emerged from between the limestone layers. On days when there is very little rain, the waterfall is diminished to a trickle, but when there is ample precipitation, the waterfall roars down and crashes onto the rocks below(sound: Waterfall 45 sec). The mist from the waterfall hits you as you pass beside it with your tour group, and the sound is echoing off the limestone walls of the entrance. A multitude of cool weather plants still thrive here during the peak of the summer heat and surround the large cave entrance. The cave air protects the delicate frills of many verdant ferns, ruby-colored columbines and ivory blooms of native hydrangea plants. You continue down the man-made path winding deeper into the mouth as the light from the sun begins to dim and the wind from the cave begins to rush toward you. It causes you to cling to the jacket that made no sense for you to bring in the late summer swelter. In the chill of the 54 degrees, though, it has become a lifeline to retain the heat next to you. The cave smells of damp earth mixed with the smell of fire that cling to clothing of camping visitors. Two polished stainless steel doors seven feet tall guard the entrance. On each side of the doors, rusty four inch wide metal bars run horizontal to the stone walls of the cave allowing the air and wildlife to travel freely. Ranger Chris pulls keys from his pocket and unlocks the door(sound: unlocking the door 8 sec). Once you step through, the wind begins to settle and the golden light of L.E.D bulbs illuminates the chamber. Entering into the first passage of the cave known as Houchins Narrows, there is a low ceiling around 5 feet high. You duck slightly as the paved trail slopes downward, allowing your head to clear the ceiling safely. In this twilight zone, sunlight can no longer penetrate the darkness of the cave. There are no animals or plants from the surface that can survive beyond this point. The only creatures that call this place home have uniquely adapted to the absolute darkness of this environment. Over 200 species live in these depths such as eyeless cave fish, eyeless crayfish, pack rats, cave crickets, pseudo scorpions, various arachnids, cave beetles, and about twelve breeds of bats to name a few. You continue walking down Houchins Narrows for several minutes until you reach a huge circular-shaped room . The expansive ¼-acre sized room extends out in front of you and has two large passages branching off of it to your left and to your right. The domed ceiling is 34 feet from the floor. This cave is considered a dry cave due to the caprock of sandstone and shale above the layers of limestone. The added layers prevent water from getting in and allows the cave passages to stay connected. Without this feature, Mammoth Cave would be a grouping of many smaller caves filled with formations like stalactites and stalagmites. No formations decorate the walls and ceilings in this section of the system. Anything that is left behind in this environment becomes preserved due to the constant climate, much like a time capsule. In the center of the room in an area that sits 10 feet below your walking path there are two large 11 feet square boxes with wooden planked sides filled with light brown dirt setting side-by-side. At the bottom of the boxes you can see tree logs that have been hollowed out and halved. These have been placed in a pattern alternating facing up and down to form an interlocking structure.

Ranger; seg. 4: Welcome to “The Rotunda”. We are now approximately 140’ below the surface. This massive room with a circular ceiling, is the result of the ancient rivers that once flowed through these passages, carving away the limestone rock. As unstable rock gave away and settled to the floor, we were left with a natural breakout dome. In addition to leaving behind large passageways, the rivers left a thick layer of sediment on the cave floor. Early settlers who entered these dry caves discovered that the sediment deposits were rich in calcium nitrate, a mineral that sparks when exposed to a flame. The settlers figured out how to leech the nitrates from the soil by gathering dirt in these boxes. They engineered a piping system from hollowed out tulip poplar trees, sharpening one end, and forcing it into the blunted end of the next log. Pipes carried water from the mouth of the cave to these dirt-filled boxes. Water poured over the layers of dirt, pulling with it the nitrates from the soil. The water would travel through the filter made by the interlocking logs at the bottom, separating debris from the nitrate rich water. The mixture was then piped to the surface and placed in large cauldrons where workers would add some ingredients and then boil it down until all that was left was a crystal known as salt petre. This crystal is the number one ingredient of gun powder. America was still young at the time of this operation and the salt petre created here became very important during the War of 1812. The war came to end it 1815 and America had maintained its freedom. Unfortunately, the majority of the workers in the salt petre production were enslaved men and would not reap the benefit of freedom for themselves. With the fall of a lucrative industry, a new chapter of Mammoth Cave would begin. The first guided cave tour is believed to have taken place in 1816. Tourism would become the new business model. As we make our way to our next stop, consider what it may have been like to traverse these passages as an early visitor touring this massive, mostly uncharted labyrinth.

Narrator; seg. 4: As you continue down the ¾ mile stretch of limestone chambers the sound of your foot steps echo through the void (sound: footsteps in the cave 30 sec). On the left of the paved stone trail there is a well worn dirt trail about 6 feet wide. It was the footpath used by the oxen pulled wagons of the mining days. Lined up against the wall are segments of the wooden pipe system showcasing the ingenuity of the early settlers. On the right of the room, limestone ruble is mounded up across an expanse 20 feet wide from the trail to the wall. In some areas the rocks almost reach the ceiling of the cavern. The ceiling is an exposed flattened slab of limestone that creates a uniform expanse as you continue down the path. The floor rises and falls as you continue through the room known as “The Church”. At the widest point, this oval shaped room is approximately 50 feet across with 35 foot tall ceilings. Beginning around 1830, on special occasions, services were held in this location. On the left, a large slab juts out from the wall about 15 feet from the path. This point became known as “Pulpit Rock”. Next to Pulpit Rock, gray boulders of limestone stretch all the way up to the roof. Black soot stains some of the rocks from guides throwing torches into darkened areas to light various features. This tradition ended in the 1990s. To the right running parallel to the path, there are two wooden pipes on triangular wood scaffolding to demonstrate how they would have been set up during the days of salt petre mining. The bottom pipe is suspended about 3 feet from the ground. The second is 3 feet directly above the first. As we leave the church the floor begins to pitch upward to Booth’s Amphitheatre on the right. Booth’s is a stony out cropping at the edge of Gothic Avenue. It is an upper level corridor overlapping the passage level you are on. In order to access this level there are about twenty stairs that lead upward. Next to the trail on the right there are three more of the wooden salt petre vats just like the ones encountered in the Rotunda. To the left of the path there is the continuation of the upper level passage but there is no easy way to access it. Piles of dirt are mounded up high on this side. The limestone walls are smooth from thousands of years of erosion. Each layer of stone is a different thickness and laid down like the layers of a cake. The spaces between known as bedding planes allow for air and moisture to travel from the outside world. These plus twenty seven known entrances and countless natural ventilation shafts allows the air to be exchanged regularly. Taking a deep breath fills your lungs with fresh cool air. Boulders of various sizes and fine grains of light brown dirt line each side of the path. Time passes as the imagery begins to blend together but then there is a sound that snaps you back. Behind the stone walls to left you can hear the sound of water (sound: water clock 11 sec).

Ranger; seg. 5: If you listen closely, you can hear an unfamiliar sound to the dryness of this section of cave. On the surface, water has found a weak spot in the caprock and over time has dripped down creating a vertical shaft. It was here that early guides would stop with their groups and tell a story of being able to tell what time it was by the steady dripping of the water. The story has been passed down through generations of guides. Earning this location the name, “The Water Clock”. Is it possible to tell the correct time by the dripping? All my sources say it is simply a tale the guides share to draw you in. The drip rate is subject to change based on rainfall. Just ahead of us is our next stop.

Narrator; seg. 5:Two more minutes of walking leads you to the next ranger stop. Visitors gather up against the left stone wall of the chamber, the ranger climbs up on a large boulder standing above the crowd. Behind the ranger there is a portion of the wall that peeled away, creating a rock 22 feet long and 12 feet wide that resembles a giant sized coffin. On the map it is referred to as the “Giant’s Coffin”.

Ranger; seg. 6: As the stories began to spread about Mammoth Cave, people began to show up from the far reaches of the world. They traveled by ships, stage coaches and trains to come here to the middle of no-where Kentucky to explore this grand, gloomy and peculiar place. Most of the guides had an elementary education and some had less than that. They didn’t know the science about how the rocks or cave had developed. They didn’t know the stories of the archaic Indian explorers. Their knowledge paled in comparison to the scholars, gentlemen and ladies that came to the door step asking for a tour. In the cave though, these guides had a skill set their visitors lacked. They could weave a tale that could cause you to forget all about the sunlit world above. There were a couple of tours offered in those days. A short trip may last anywhere from 6 to 9 hours or a long trip that could last around 15 hours. Behind me, Guides would create shadows on the wall of this stone coffin. They told stories of the giants that once roamed these lands. Inside this coffin is the smallest giant of them all. He created the chambers we walk through today by arching his back up and against the earth, forcing the land above to build up. Everyday the giant would come to the cave to check on the cave creatures within. He guarded the cave and everything in it. One day the giant fell ill, when he passed his body was laid to rest here in the cave. Some say when the moon and the stars are aligned just right, a cave guide can lift the lid of the coffin. This illusion can be created with complete darkness and a singular lantern. On the back wall the silhouette of the coffin is caste, by moving the lantern up and down it gives the illusion that the lid is lifting. At the forefront of the Mammoth Cave experience was always the guide. In 1838, a young enslaved man named Stephen Bishop was brought to the cave. He was sold, along with the cave, to a doctor from Louisville Kentucky. This doctor, John Croghan, would change the vision of what Mammoth Cave could be, and Stephen would help make that dream a reality. Improvements were made to the Hotel on the surface and Stephen would expand the known length of Mammoth through his exploration. Aside from being a great cave explorer, he was also quite the entertainer. In the almost 20 years that he led tours through the cave, Stephen would lead prominent members of society through the rugged terrain, intriguing them with his knowledge and storytelling. Individuals, like the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson, would make the long journey to Kentucky with the purpose of seeing the great underground marvel and afterwards, would write of their experiences and mention the guides by name. The stories of Mammoth Cave do not stop here. For almost 90 more years, visitors, guides, and the cave itself would continue to develop an intricate network of history and science that elevated us to where we are today. There is no way to share, or even to fully understand, all the stories that this unique place has woven into it. Hopefully, in the short time that we have spent together, you realize, with just a few of those stories, how connected this underground world has been to the historical realities on the surface above it. A connection, so profound, it was worthy of being dedicated as your 26th National Park.

Narrator; seg. 6: As Ranger Chris steps back onto the paved trail, a loose rock sways under his boot and lands back in place with a resounding clank, mimicking the first sound made by humans entering the cave. To this day, visitors pause to experience the silence that otherwise consumes the cave. Silence that humans have broken with their footsteps, their voices, and even musical instruments. From far and wide, musicians have come to this stone performance hall to partake in the unique acoustics. Echoing through the ages are the sounds of the soulful songs of the enslaved people, the violin of an early cartographer; Max Kaemper, multiphonic chanting of Buddhist Monks, and the modern day songs inspired by the cave. As we continue our trip back to the warmth of the world above, we close our tour with the sounds of one of those songs: “My Ole Kentucky Home” performed in the halls of Mammoth Cave by former Cave Guide Dr. Janet Bass Smith on piano, accompanied by Klaus Kaemper (descendant of Max Kaemper) playing cello. (Building music: “My Ole Kentucky Home” 2min 26secs)