|

The museum and archival collections at Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site contain a number of objects related to slavery and the abolition movement in the United States. Abolitionists sought out poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, his family members, and friends at the family home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Friends and visitors included Richard Henry Dana, Jr., Charles Sumner, James Russell Lowell, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lydia Maria Child, Lunsford Lane, and Josiah Henson. Their correspondence, pamphlets, and family journals constitute a significant anti-slavery research collection, available to researchers by appointment. Longfellow Family PapersThe Longfellow family gathered books, clippings, pamphlets, speeches, and other source materials documenting the developing national crisis. Their personal journals and letters, held in several collections, provide candid first-person viewpoints of daily events. Fanny Longfellow's papers include her extensive correspondence, in which she is outspoken about her abhorrence of slavery. Particularly interesting for study are her letters to and about Senator Charles Sumner, Fanny Kemble, and her family and friends living in the South. Henry Longfellow's brother, Reverend Samuel Longfellow, likewise expressed his strong antislavery views in his personal correspondence. He also used his pulpit to speak out against the institution, as in a 1856 revision to a 1848 sermon calling slavery a “practical denial of human brotherhood” and would have been condemned by Jesus. The Longfellow children grew up in a household steeped in political thought. Charles Longfellow's papers include documentation of his Civil War service. Alice Longfellow, eleven at the outbreak of the Civil War, collected patriotic cachets during the war, including many with anti-slavery rhetoric. Longfellow Family LibraryThe Longfellows' library includes books reflecting their interest in the anti-slavery movement, both as it unfolded around them and in retrospect after the close of the Civil War. Among the books in the collection clearly identified as belonging to Henry Longfellow are:

In addition to consuming anti-slavery literature, Henry Longfellow wrote antislavery poems. Eight of these were published as a stand-alone volume, Poems on Slavery (1842). He contributed two additional poems to The Liberty Bell, published by the American Anti-Slavery Society: “The Norman Baron” (1845) and “The Poet of Miletus” (1846). Samuel Longfellow contributed two of his own poems to The Liberty Bell: “The Word” (1851), and “Hymn” or “O God, in whom we live and move” (1856). Dana Family PapersThe archives contain material related to the legal career and antislavery activities of Richard Henry Dana, Jr., the Longfellows' Cambridge neighbor and father-in-law of Edith (Longfellow) Dana, in the Dana Family Papers, 1661-1960. Richard Henry Dana Jr. is best-known as the author of Two Years Before the Mast (1840), a narrative of sea voyages that heightened his sensitivity to exploitation. Graduating from Harvard Law School in 1839, he published Cruelty to Seamen and began practicing law, holding numerous public service positions, and serving as U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts. Dana helped to found the Free-Soil party in 1848, a forerunner of the anti-slavery Republican party; and defended African-Americans who fought their return to slavery under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. He also defended those who assisted slaves and were subject to harsh punishments under the law. In later years he noted that his work on behalf of Shadrach Minkins and Anthony Burns was the “one great act” of his life. Shadrack Minkins escaped from slavery in Virginia in 1850, and sought refuge in Boston. In 1851, police captured and charged him under the Fugitive Slave Act, permitting slave owners to retrieve runaways from free states. Outraged Boston citizens seized Minkins and conveyed him to Canada and freedom. Dana’s hand-written trial transcripts document escalating tensions between abolitionists and slaveholders.

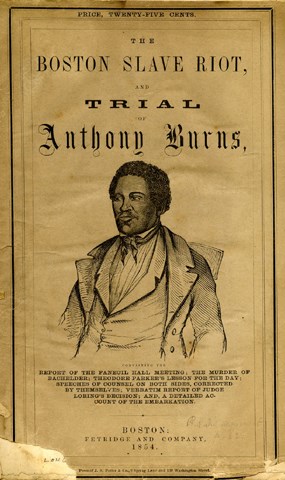

Dana Family Papers (LONG 27037) Anthony Burns TrialBurns escaped from slavery in Virginia and came to Massachusetts. As a result of the Fugitive Slave Act, passed in 1850, slave hunters were able to arrest him in Boston. A group of abolitionists attempted to storm the courthouse where Burns was held in order to rescue him, but they were unsuccessful. Dana and African American lawyer Robert Morris represented him at trial, but Burns lost his case. In a letter to his friend Senator Charles Sumner, dated 2 June 1854, Henry Longfellow wrote "To-day is decided the fate of Burns, the fugitive slave. You have read it all in the papers, -the arrest, the trial, etc. Dana has done nobly; acting throughout with the greatest nerve and intrepidity." After the failed rescue attempt and loss at trial, outraged citizens lined the streets yelling “Kidnapping!” as Federal officers marched Burns to the ship returning him to slavery in Virginia, where his previous owner imprisoned him until he was sold to another party. The case triggered massive opposition to the Act and hastened its repeal. The Dana Family Papers, 1661-1960, include documentation of the trial and resulting riots, a pamphlet on Burns’ life, and Dana’s speech on removing the officer who presided over the Burns case and returned him to slavery. Collected ItemsAmong the objects transferred to the National Park Service by Longfellow's descendants are slavery-related documents of uncertain provenance. Though they are out of context, each of these items tells a piece of the story of slavery in America.

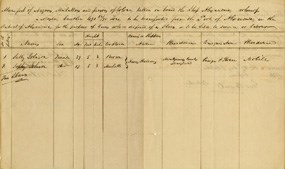

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Collected Materials, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Family Papers, LONG 27930 "Manifest of Negroes, Mulattoes and persons of Colour," taken on board the Ship AlexandriaThis ship's manifest, dated 29 October 1836, lists “Two Slaves," Sally Johnson age 39, and Sophy Johnson age 17, and the name of their shipper, Henry Harding. The document indicates that the women are being taken from the “Port of Alexandria in the District of Alexandria for the purpose of being sold or disposed of as Slaves, or to be held to service or labour." Written on the other side of the document is a statement that Mr. Harding does "solemnly, sincerely and truly swear ... that the negroes herein setforth, have not been imported into the United States, since the first day of January one thousand eight hundred and eight." Importation of slaves into the United States was legally banned after 1807. The law did not forbid the sale of enslaved people already within the U.S. though, and illegal slave trading continued right up until the Civil War.

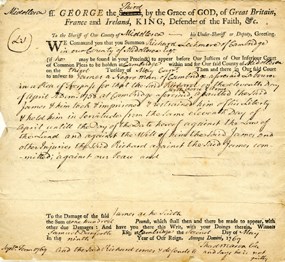

Professional Legal Records, Francis Dana Personal Papers, in the Dana Family Papers, LONG 27037 Court Document, 1769This document is a summons issued to Richard Lechmere of Cambridge to appear before the court and answer to charges that he unlawfully imprisoned and restrained "James a Negro man of Cambridge." James was enslaved by Richard Lechmere, yet brough this suit against his owner. Francis Dana served as counsel to James in the case. The Inferior Court, to which this document refers, ruled in favor of Lechmere. However, the case was advanced to the Superior Court. Before the case was resolved there, Lechmere settled with James, granting him his freedom as well as £2. Lechmere built a house on Brattle Street, not far from the mansion built for John Vassall in 1759, now Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site. |

Last updated: July 23, 2024