Museum Collection (LONG 22974)

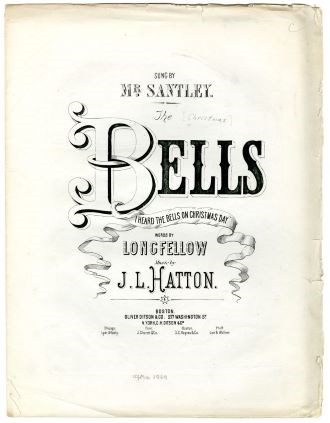

After “Paul Revere’s Ride,” “Christmas Bells” is probably Longfellow’s best-known poem today. Set to music early on, the poem became part of the Christmas carol canon. The words have been paired with both traditional melodies and new compositions too numerous to list, in styles ranging from sacred to pop. Two tunes are most familiar today: the hymnal version set to “Waltham,” first used in the 1870s, and the popular version written by Johnny Marks in the 1950s and recorded by artists from Bing Crosby to Harry Belafonte to The Carpenters (amongst many others). If you’re familiar with the carol, there’s a good chance reading the first stanza triggers one of those tunes in your head .

The church bells ringing to mark the holiday are the central image of the poem. In the last line of each stanza, the bells speak to the poet of peace and good-will. His choice of meter echoes the “ringing, singing” tones of the bells. Longfellow used the image of bells in several poems. In the last poem he wrote, “Bells of San Blas,” he calls bells, “the voice of the church,” noting that in hearing, each individual “Lends a meaning to their speech / And the meaning is manifold.” The imagery is open to interpretation – what do you hear in the sound of the bells?

These two stanzas, usually left out of the carol version, evoke the context of sorrow in which the poem was written, and the experience of its audience when it was first published in February 1865. The American Civil War was a national tragedy on a staggering scale. Modern scholars estimate that at least 750,000 men died in the four years of war. Many thousands more were wounded and the effects were felt in households far removed from the front lines. Longfellow wrote “Christmas Bells” in 1864.1 However, he had begun finding the phrases to capture his outlook on the war long before sitting down to write this poem. In September 1862, on hearing of the battle at Second Manassas, he reflected in his journal: “Every shell from the cannon’s mouth bursts not only on the battle-field, but in far-away homes, North or South, carrying Dismay and death. What an infernal thing war is!”

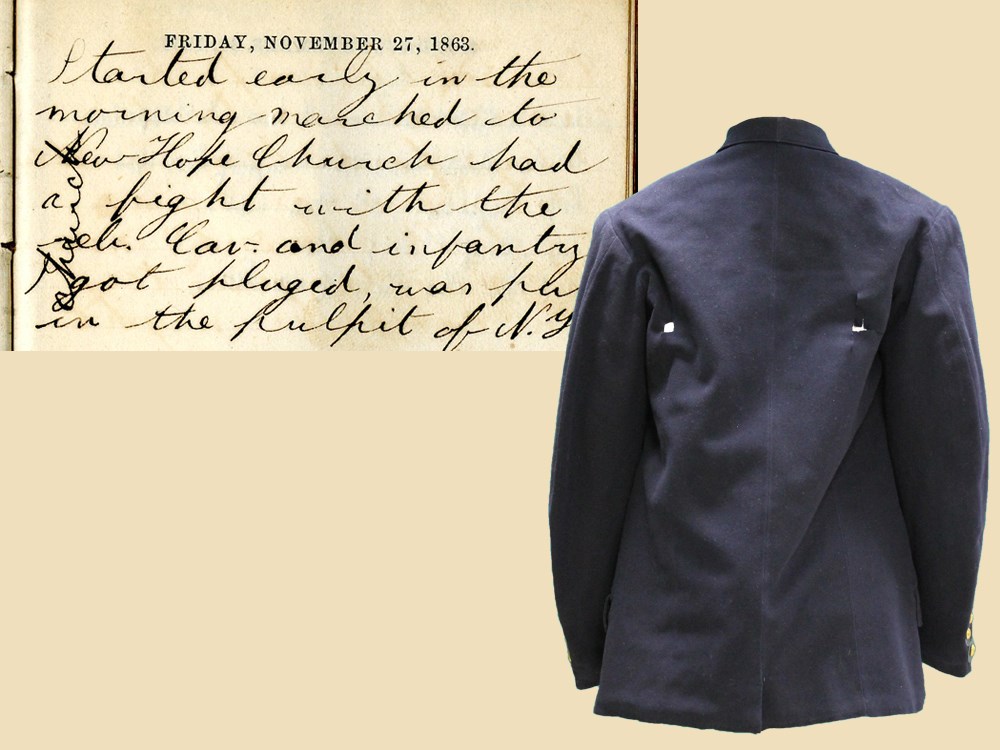

His journal entry reads: "Started early in the morning marched to New Hope Church had a fight with the reb. Cav. and infantry I got pluged [sic], was put in the pulpit of N.H. church." The Civil War touched Longfellow’s family when in March 1863 his oldest son Charley ran away to join the Union Army. That November, Charley coolly commented in his journal that he “got pluged [sic]” in the Mine Run campaign – actually a severe gunshot wound through his back. Henry Longfellow went to Washington, D.C. and escorted his son home for his long convalescence.

Museum Collection

The trauma of Charley’s injury occurred on top of the pain of the loss of Fanny Longfellow, who died in an accidental fire in July 1861. On the first Christmas day after her death, Longfellow reflected: “How inexpressibly sad are all holidays! But the dear little girls had their Christmas-tree last night; and an unseen presence blessed the scene.” The loss of his wife marked Longfellow for the rest of his life.

Both the poem and carol end with an uplifting resolution of peace on earth, heard in the ringing of the bells. This message continued to resonate over the next century, particularly in times of national crisis. Longfellow’s granddaughter Erica Thorp, writing home from war-torn France at the close of World War I, consciously or unconsciously echoed the poet’s phrases:

In December 1943, during another world war, a letter to the editor in a New Bedford newspaper used the poem as a touchstone for “The Christmas Spirit In a World at War,” opening: “’Peace on earth, good-will to men.’ With the pall of war hanging over the world it seems almost sacrilegious to speak these beautiful words today.”3 Five years later, after the close of World War II’s hostilities and the onset of the Cold War, another newspaper published the poem and a piece on its Civil War context, reflecting, “Just as so many in our time are wondering if ever again we will dwell in a world of concord, Longfellow voiced the doubt and fear of that era…”4 In the modern era, the carol version of Longfellow’s poem has become part of the Christmas carol canon. Recordings by Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby remain holiday classics, and modern artists continue to record covers of the song every year. The tension between Longfellow’s despair at the state of the world around him and hope for the future that breaths from this poem rings true to people in every generation – from Longfellow’s to our own.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Ranger Kate reads Longfellow's iconic poem from his Cambridge study. Notes

|

Last updated: December 17, 2020