Volcanic Hazards Q&A

Q: Will Lassen Peak erupt again and if so, when?

A: No one can say for sure or when. However, Lassen Peak is considered active because it last erupted about 100 years ago (read more). Geologically recent volcanic activity in an area is the best guide to forecasting future eruptions. Park hydrothermal areas linked to active volcanism are also evidence of the ongoing potential for eruptions in the Lassen area.

Q: How are volcanoes in Lassen Volcanic being monitored?

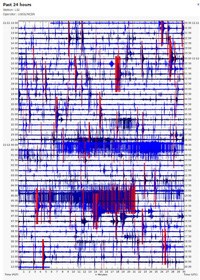

A: Scientists at California Volcano Observatory (CalVO) in Menlo Park remotely monitor data for seismometers located throughout the park. The most important sign of an impending volcanic eruption is seismic activity (earthquakes) beneath the volcanic area. You can view the same data the scientists monitor on the USGS real-time monitoring map. USGS has identified the Lassen Volcanic Center, which includes all volcanoes within the park and surrounding area, as one of 18 very high threat potential volcanoes in the nation. These volcanoes are prioritized for research, hazard assessment, emergency planning, and volcano monitoring.

Q: How will we know if a volcano in the park is going to erupt?

A: USGS uses a four-tiered threat level system to specify threat on the ground or to aviation. Individuals can subscribe to a free email-based notification service at https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/vns2/. This system also provides information to media and emergency response providers who will issue local alerts.

Q: What hazards are expected from a future eruption in the Lassen Volcanic Center (LVC)?

A: All four types of volcanoes in the world are found within the park. Each type of volcano has specific hazards. View the USGS Volcano Hazards Assessment for the Lassen Region for more information.

- Small basaltic lava flows and small associated local ash falls are the most common volcanic activity in the LVC. They are relatively nonviolent and rarely impact populations.

- Silicic lava flows (like dacite) have formed lava domes in the park, which can collapse to produce block and ash flows that travel several miles.

- Volcanic ash can rise several kilometers into the atmosphere when dacite magma charged with volcanic gases reaches the surface. Fallout from the eruption column can blanket areas within a few kilometers of the vent with a thick layer of tephra and winds may carry finer ash tens to hundreds of kilometers, posing a hazard to aircraft.

- Pyroclastic flows may form when a dacite magma eruption column collapses sending a hot chaotic mixture of rock, gas, and ash several kilometers down a volcano's slope.

- Lahars form when pyroclastic flows mix with large quantities of water (like melted snow) and can produce flows of mud and debris that rush down valleys leading away from a volcano. A lahar formed the Devastated Area in the park in 1915.

- Landslide and rockfalls have occurred in the park and were not directly related to eruptions. The collapse of one of the Chaos Crags domes approximately 350 years ago created a huge rockfall that climbed 400 feet up an adjacent mountain. This was likely caused by an earthquake. Normal weathering also weakens fractured volcanic rock and contributes to small rockfalls.