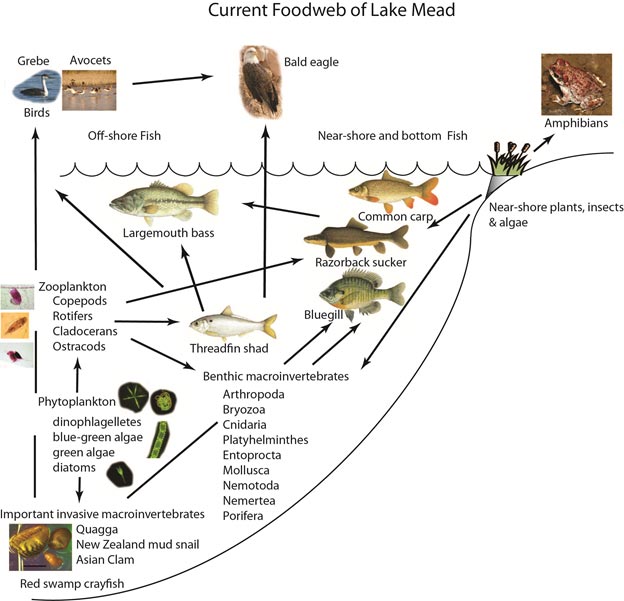

Food Webs: A Bird’s Eye ViewWheeling and diving in the sky, peregrine falcons are among the most entertaining residents of lakes Mead and Mohave. Beyond their amusing antics, these birds illustrate the interconnectedness of the species in an ecosystem – who eats who, why it matters, and what can go wrong as a result of each link’s close dependence on the other species. In any ecosystem, big charismatic creatures like peregrine falcons steal most of the limelight. However, it’s the tiniest organisms that are most critical because everything else depends on them. In lakes Mead and Mohave, it’s the microscopic algae and phytoplankton that form the base of the food web making all other life possible. These organisms create their own food, photosynthesizing energy from the sun’s rays. They in turn serve as a food source for other creatures in the water. Phytoplankton feed small creatures like crayfish and snails that live at the bottom of the lake, also tiny free floating organisms called zooplankton which live in the open water. Zooplankton are the main food source for fish like bluegill and shad, which form the majority of the diet of the substantial bass population in the lakes.  Algae, phytoplankton and zooplankton are tiny but vital lake inhabitants. They are closely dependent on each other and are sensitive to changes in the lake and its food web. Their populations rise and fall in response to increasing and decreasing nutrients like phosphorus, changing water temperatures or contaminant loads, and the introduction of invasive species. As the primary producers of food, they are excellent indicators of the overall health of the ecosystem. Ensuring that these tiny organisms exist in a balance is the goal of most water quality management and treatment initiatives worldwide.

Phytoplankton and zooplankton are tiny but vital lake inhabitants. The resource managers for lakes Mead and Mohave are concerned that the invasive quagga mussels, lowering lake levels, and changes in nutrient levels in Lake Mead may alter the balances of phytoplankton and zooplankton in the lakes, possibly degrading the primary foodweb. Plankton are sampled monthly from all areas of the lakes, and recent analysis of that data1 from 2007 through 2013 shows that for now, the overall plankton balance and number of species is still within ranges to support a healthy food web.2 2 Plankton Diversity: Is it influenced by tributaries to Lake Mead?

Left to right: Red-tailed Hawk; Golden Eagle; Peregrine Falcon; Bald Eagle Birds are higher up in the lakes’ food web; aquatic birds like avocets and grebes also feed on small invertebrates that lurk near the lake bottoms. At the very top of the food web sit predatory fish like striped bass and predatory birds called raptors. Raptors3 include osprey which eat fish, peregrine falcons which feed on aquatic birds, and bald eagles which eat both fish and other birds.

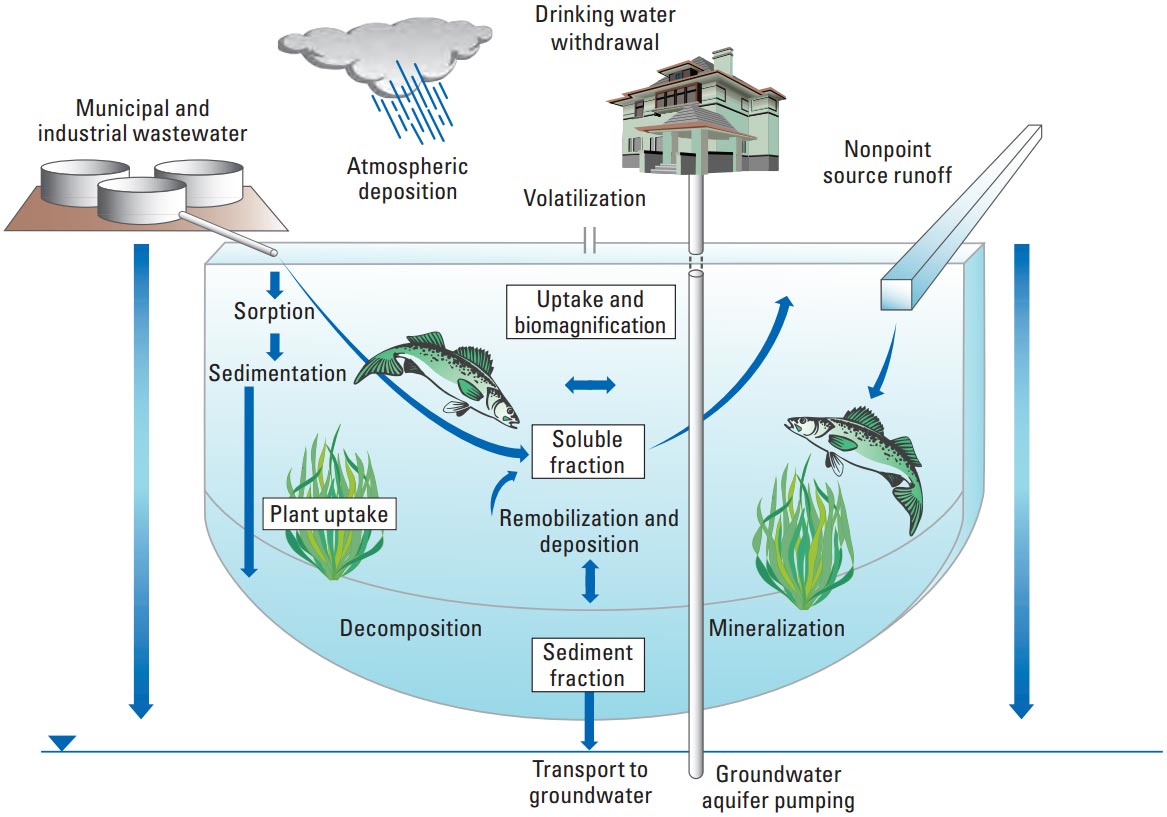

Sources and pathways of organic compounds in water and aquatic ecosystems. Thanks to new research, peregrine falcons are revealing a fascinating story about how contaminants can move through the food web at lakes Mead and Mohave. Peregrine falcons have staged an amazing comeback in this area over the last few decades, but recently, workers around these reservoirs have identified a potential problem: surprisingly high levels of mercury in the birds’ bodies. Mercury4 can enter an ecosystem either via natural processes like slowly leeching out of rocks, or as a byproduct of human activities such as burning coal and mining. After entering an aquatic ecosystem like lakes Mead and Mohave, the mercury is first processed by bacteria which convert it into an even nastier substance called methylmercury. This contaminant is then taken up by plankton which are eaten by invertebrates and fish, and continuing on with each organism in the food web consuming the next. As the methylmercury makes its way through the food web, it biomagnifies – in other words, it becomes increasingly more concentrated in each consecutive organism’s body. By the time the methylmercury gets into the bodies of peregrine falcons, it can reach very high levels. When this happens, it can affect the nervous system, especially in developing birds. Young peregrine falcons are the ones most at risk; if enough mercury gets concentrated in their bodies, they could have trouble learning to hunt and fly. However, this doesn’t pose a complete disaster for local peregrines – at least not yet. Although researchers have measured high levels of mercury in the birds, they haven’t seen any actual deaths or health consequences. Also puzzling is the fact that overall mercury concentrations in Lake Mead water and in fish sampled from lakes Mead and Mohave is generally low, well within lower ranges of large lakes around the country. Biologists want to keep an eye on the situation by testing birds’ feathers to assess whether contaminant levels are increasing, and monitoring the local peregrines’ population to determine whether their numbers are falling. The lakes wouldn’t be the same without the freewheeling falcons that perch high on the rocky cliffs and also atop the lakes’ delicate food webs. The Effects of Change

A researcher collecting data used to help answer critical questions about lake health. Ecosystems are naturally resilient and can usually bounce back in response to changing conditions, but lakes Mead and Mohave have recently been hit hard with two big changes: the invasion of quagga mussels and the lengthy drought that has been plaguing the Southwest. Scientists are working hard to determine whether the lakes’ food webs can cope with the new conditions or if these upheavals have unsettled the basic biological relationships that keep the lakes healthy. Read MoreHow to Measure Mercury

This peregrine falcon nestling will be tested for signs of mercury by clipping off a tiny piece of one of its feathers. Studying big, powerful, sharp-taloned birds of prey like peregrine falcons takes a special kind of scientist. Not only are the birds challenging to work with, but this kind of research requires an eclectic combination of approaches that range from rappelling down vertical cliff faces to performing careful analyses in the laboratory. |

Last updated: January 18, 2018