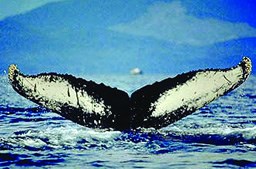

NOAA photo / J. Waite Megaptera novaeangliaeBasic FactsThe humpback whale is a member of the Balaenopteridae family of baleen whales. Whales in this group feed by straining prey through baleen plates lining the roof of their mouths. Male humpbacks reach an average of 46 feet and 25 tons, females an average of 49 feet and 35 tons. The humpback has a distinctive body shape and unusually long pectoral fins (flippers), which are nearly one-third of their total body length. The dorsal fin shape varies, but is often a small triangular nubbin with a step or hump most noticeable when the whale arches its back to dive and from which it derives its common name. They are often white or partially white in color and the underside of the fluke (tail) often has white markings unique to each whale. Humpback whales are listed as an endangered species with a worldwide population estimated in 2007 at 30,000 to 40,000 whales. The North Pacific population seen in Alaska is estimated at around 6,000 whales. Habitat, Range and Local SightingsHumpbacks travel between winter breeding grounds and summer feeding grounds. The animals that spend their summer in Kenai Fjords National Park winter in Hawaii and Mexico, and may travel as far as the Chukchi Sea. Locally, we find humpback whales throughout Resurrection Bay and the waters surrounding Kenai Fjords National Park. Several spots near the Chiswell Islands also attract feeding humpbacks. Food and Survival StrategiesHumpback whales spend from mid-April until November feeding around Kenai Fjords National Park. Each day a humpback eats approximately a ton of food. When feeding, 12 to 36 ventral throat grooves allow a humpback whale’s mouth to swell to enormous proportions. A humpback can hold 500 gallons of seawater laden with prey in its mouth. Using its tongue, the animal pushes the water out through up to 400 two-foot long baleen plates hanging down from each side of its upper jaw. The prey catches on the baleen and is swallowed. Euphausiids (krill), copepods, and small schooling fish, such as white capelin and herring, make up much of a humpback’s diet. Reproduction and YoungHumpbacks breed and give birth during the winter months in Hawaii and Mexico. Gestation lasts about 11 months, and every one to three years a single calf is born. Twinning happens occasionally, but often only one animal will survive. At birth, a calf is 16 feet long and weighs two tons. Humpback calves stay with their mothers and nurse heavily, building a fat layer, before making their first migration north to Alaska’s cold waters. Young calves, as well as older whales, must watch out for transient orcas, their biggest predator. Male humpback whales sing songs in their winter breeding grounds. The songs contain two to eight “themes” always sung in sequence. A whale can sing for 20 minutes or as much as seven hours. Singing may be used to show a whale’s dominance among males competing for a female. Male humpbacks interested in mating with a female become her “escort.” They follow behind and below a female cow and calf, waiting until the female is receptive. A male sometimes instigates a skirmish using its barnacle encrusted chin and the front edge of its pectoral fins as weapons against a rival. Older males often show scarring along their backs from these interactions. Human ConnectionsThe extensive migration of the humpback whale underscores how rich an environment the Kenai Fjords ecosystem is: Swimming nearly 3,000 miles, the humpback comes all the way to Alaska to feed. Here, it finds water with enough nutrients and oxygen to support the volume of food necessary for its sustenance. During the summer months, it is able to add the three to four inches of blubber necessary to see it through the winter. Historically, humpbacks were hunted for their oil, meat, and baleen. Humpbacks proved an easy target for hunters because they tend to feed close to land. By the time a ban on international whaling was drawn up in 1964, the population of humpback whales was as low as 1,000 animals. A comprehensive study known as the Structure of Populations, Levels of Abundance and Status of Humpback Whales, or SPLASH, initiated in December 2003, hopes to further refine our knowledge of North Pacific humpback populations. SPLASH research took place in Russia, Mexico, Alaska, and the Philippines. The research goal is to understand population structure and assess status trends and human impacts to the humpback population. |

Last updated: March 15, 2018