Much of what we know today about the early American period of Alaska is due to the pioneering efforts of one man, Ivan Petroff. He is largely responsible for compiling the US Census for this territory twice, in 1880 and 1890, as well as exploring and publishing on many areas along the Alaskan coast. As a ranger in Katmai National Park I often reference Mr. Petroff, for he collected the only ethnographic account of the native village at Brooks Camp that I am aware of. In many ways this Russian transplant was the leading American authority on Alaska of his day, a prominent position he held until he was discredited in a most public and humiliating manor during tense international negotiations. Does that not read like a high powered plot in a John Gisham inspired best seller?

Much of what we know today about the early American period of Alaska is due to the pioneering efforts of one man, Ivan Petroff. He is largely responsible for compiling the US Census for this territory twice, in 1880 and 1890, as well as exploring and publishing on many areas along the Alaskan coast. As a ranger in Katmai National Park I often reference Mr. Petroff, for he collected the only ethnographic account of the native village at Brooks Camp that I am aware of. In many ways this Russian transplant was the leading American authority on Alaska of his day, a prominent position he held until he was discredited in a most public and humiliating manor during tense international negotiations. Does that not read like a high powered plot in a John Gisham inspired best seller?

Ivan Petroff's connection with Katmai began in 1880, when he undertook the mammoth project of conducting the US census for the entire Alaska territory single handed. This project would take some two years, of which Mr. Petroff traveled 2400 miles by open boat in the first year alone (Pierce 1968:6). As he paddled the shoreline of the Bering Sea, the intrepid census taker turned up the Naknek River into the Naknek Lake drainage (which he renamed “Lake Walker” for his supervisor), eventually making his way overland to Katmai village on the Pacific coast side of the Alaska Peninsula. This occurred just eight years after Alphonse Pinart was making his own journey through Katmai village, collecting vocabularies and other specimens of an anthropological nature.

This journey brought him through the heart of the modern park, and sometime on or before October 2, 1880 he paddled by where I live for the summer, Brooks Camp (Dummond 2005:72). Until roughly AD 1800 Brooks Camp was known by many different names, for the archaeology here has revealed a series of native settlements and camps stretching from roughly that year and going back 4,500 years.

The Brooks River area and Iliuk Arm of Naknek Lake (left) inspired this painting (right) based on Petroff's written description. NPS

Apparently talking either to his hired native helpers or other locals Petroff recorded a remarkable anecdote that may explain the abandonment of a village on the Brooks River. I have found two versions of this account. The first was originally published in the January 11, 1881 edition of the New York Herald.

At the eastern extremity of this large inland water a section of it is almost separated by a dam of mountains, communicating with the main body by a gap of less than half a mile in width. Stupendous heights surround this nook, rising almost perpendicularly from the surface and reaching far into the clouds. In this confined, funnel-like basin, the winds and squalls hold constant carnival... At the western end of this lakelet a numerous party of natives were engaged in fishing just below a waterfall of considerable height.... A village was formerly located here, and a legend is transmitted that once in times gone by the whole population was killed by a marauding party of Aleuts, who surprised the settlement in the dead of night. The tale was told by one survivor who hid himself under the waterfall, and thus escaped the enemy. (Dummond 2005: 72-73)

The second is quoted from Ivan Petroff's opus, the 1884 Report on the Population, Industries, and Resources of Alaska.

The people of Port Moller and Oogashik are of the Aleutian tribe, which in former years made warlike expeditions along this coast, extending as far to the northward as the Naknek river and Lake Walker. At the village situated on one of the feeders of the latter lake the present inhabitants still tell the story of the night attack made by the “bloodthirsty” Aleuts long ago, when every soul in the place was dispatched without mercy, with the exception of one man, who hid himself under a waterfall close by, and thus survived to tell the tale. (Petroff 1884:24)

For every student of this region these accounts comprise all the ethnographic data we have on the abandonment of the native village. Undoubtedly significant, but Petroff's stories do suffer from a lack of detail and what detail that is present appears contradictory. As I examine these brief narratives I can picture Mr. Petroff coming across a group of native anglers at their fishing camp on the lake. There are two streams with waterfalls near the western end of Naknek Lake, Margot Creek and Brooks River, but only the banks of Brooks River exhibit signs of a native village. Could this village be the site of a massacre?

When Russian explorers came to the mouth of the Naknek River in 1818, they found a Yupik Eskimo settlement relatively recently established. These natives were refugees of warfare further north, and had settled this part of the Bristol Bay coastline after forcing the original inhabitants inland along the rivers (Dummond 2005:48). The original inhabitants would have been called Aleuts by the Russians of the time. (This was part of a larger period of wars known as the “War of the Eye,” which makes for some very interesting reading for those so inclined.)

The original inhabitants at the mouth of the Naknek River were forced upriver to a settlement even further east than Brooks Camp, a village the Russians called Severnoskoe (Savonoski). To make things even more confusing, the Russians referred to two different tribes (Unangan and Alutiiq) by the same name of Aleut, seen by them as distinct from the Eskimo groups further north. Modern scholarship considers the former inhabitants of Severnoskoe to be Alutiiq. The Unangan people probably should be more closely identified with the term Aleut, and are located further south along the Alaska Peninsula.

So we have a period of regional instability and war, as a Yupik Eskimo group pushed Alutiiq (Aleut) residents out of the Naknek River and perhaps from the shores of Lake Naknek as well. So who attacked who at Brooks Camp? Excavations reveal Alutiiq artifacts and houses, but Petroff recorded that the Aleuts (probably Alutiiq) were the aggressors. Was Petroff confused? Was a roving band of Unangan raiders pillaging this far inland? Perhaps the eskimo invaders had captures the village previously, only to be attacked by the frustrated former inhabitants? Could Petroff's informants have been mistaken? Is the whole story suspect? We just don't know, and the known facts of Petroff's life often differed from the stories that he told about himself! No one can argue that his Brooks Camp narrative makes for an exciting story, and therein may lie a clue to the story's truth.

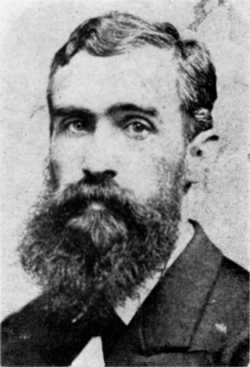

The life of Ivan Petroff was certainly never short of adventure. A short biographical sketch of Petroff was published in another work that he helped write, the well respected and thorough ~39 volume history of the Americas spearheaded by the wealthy publisher Hubert Howe Bancroft (1890:270-271). Faithful readers may note that the publishers Bancroft as well as Katmai village are two points of connection between the checkered careers of the savants Ivan Petroff and Alphonse Pinart.

Ivan Petroff was born May 3, 1842 near St. Petersburg, Russia, to his father Ivan Petroff and his mother Sophia Lanin (Pierce 1968:2). Ivan was orphaned as early as his 12thyear, when his soldier father was reportedly killed in battle in the Crimean War (Bancroft 1890:270). All sources agree that Petroff showed great promise in his facility with languages. The Bancroft account states that Ivan was initially enrolled as a military cadet for training as an official interpreter in the Imperial Academy of Sciences, a career unmade by an illness that resulted in a speech impediment in the young man (Bancroft 1890:270). I have no record if Ivan carried a speech impediment through the rest of his life. His “official” biography then describes training and fieldwork in linguistics, as Ivan Petroff assisted in the compilation of a Sanskrit dictionary with a Professor Bohttink and in two years of fieldwork in the Caucasus with Professor Brosset.

So far Petroff’s career is apparently one of diligence and field experience, but close examination begins to unravel several of his claims. Professor Bohtingk (Bohttink?) did compile a Sanskrit lexicon, but Ivan Petroff must have been a very able linguist to assist at his then seventeen years of age, and further Professor Brosset did his fieldwork in Armenia and Georgia when Ivan was only five or six years old (Pierce 1968:2). Are both experiences fabricated?

More discrepancies can be found. Petroff made his way to the United States as early as 1861. All sources agree that the young immigrant eventually joined the Union Army in the Civil War. According to Bancroft he served with distinction, eventually being promoted to an officer after gallantry in combat at Fort Fisher. Supposedly after leaving the service at the cessation of hostilities, Petroff sought and gained employment with the Russian American Company in Alaska, being “Satisfied that Alaska would one day become the property of the United States” (Bancroft 1890:271).

Regrettably no record exists for Ivan Petroff's heroicmilitary service. Ivan's daughter would later recall that her father had enlisted under the assumed name of John Meyers. A John Meyer is found in the records. He was a 21 year old Russian from St. Petersburg who enlisted in 1863 as a private and deserted a little over a year later in 1864 (Pierce 1968:2). No officer promoted for bravery then, but Ivan did run a great risk, as punishment for desertion could include execution or branding!

Ivan Petroff is found enlisted again in the army in July 1867, this time in Washington Territory. Barely eleven months later Petroff deserted the army for a second time, and was duly caught and imprisoned. Ironically, his facility with languages saved him, for he deserted his company right before its deployment to Alaska. His former commanding officer requested that Ivan accompany them and serve as an interpreter in Kodiak, saving his erstwhile private from punishment. Ivan Petroff served out the rest of his service by 1870, and re-enlisted again early the next year. Incredibly Ivan deserted the army for a third and final time later the same year (Pierce 1968:3)!

After his checkered career in the military, Petroff settled down in San Francisco in the newspaper industry. Ivan continued writing and, through the mediation of a US senator, weathered an 1875 arrest by the still disgruntled army over his latest desertion. 1876 witnessed Petroff marrying a local woman, Emma Stanfield. By 1878 Ivan became the foreign editor for the San Francisco Chronicle, lauded for his journalistic talent. That respect held until one of his foreign editorials was reprinted next to an identical article from the London Times (Pierce 1968:4). This obvious plagiarism ended Ivan's job and his respectability in journalism, at least in San Francisco.

While his career in journalism was ruined, again Ivan Petroff found employment through his facility with languages. Apparently impressed with his talents, Hubert Bancroft employed Petroff from roughly 1875 until 1880 as a translator and writer on his massive histories of the Pacific Coast territories. As a mark of his favor Petroff traveled extensively in Alaska twice for his employer to gather materials, as well as working from California and Washington, DC. This later journey brought him the political connections to conduct the Alaska section of the US Tenth Census as well as serving as the collector of US customs on Kodiak Island. By the time Ivan Petroff served with the US Eleventh Census in 1890 he was 48 and a respected civil servant. Due to his prodigious research and well received publications, Ivan Petroff was considered one of the foremost subject matter experts on Alaska.

While finishing his work on the Eleventh Census, Ivan Petroff assisted the State Department in 1892 in translating Russian documents pertaining to territorial rights in the Bering Sea. The United States and Great Britain were then submitting their arguments regarding the open-sea hunting of the Pribilof Island seals to international arbitration. The US was insistent that they had the authority to enforce hunting regulations, partially based on the US inheriting a special sphere of influence in the Bering Sea from Russia with her purchase of the territory in 1867. Ivan Petroff was contacted to translate Russian documents that hopefully supported this stance.

Petroff did his work in what appeared an admirable manner; his translations proved to be very supportive of the US position. However, this caused acute embarrassment within the administration of President Cleveland when it was discovered that Ivan Petroff intentionally altered his translations to support his employers! Ivan Petroff’s work had already been submitted to the arbitrators, necessitating the US to send diplomatic cables striking his work from the process. The translations of Ivan Petroff contained deliberate falsifications, a brazen act that trusted that no other person with a command of the Russian language would examine the evidence presented to the arbitrators.

Ivan Petroff’s public life was ended with this last act of less than honorable decision making. The Bering Sea arbitration was eventually decided against the case of the United States, and in the many decades since other works of Ivan Petroff have come under scrutiny for their authenticity. Some of Petroff’s sources or translations have been shown to be certainly embellished or outright falsifications, while his other work (such as the census of 1880) is largely considered valuable, but lapses in his research integrity stain even these works. Working under an assumed name, Ivan Petroff passed away in 1896 in Philadelphia, PA.

Where does this fascinating if checkered career of an early explorer leave Katmai? The story of the abandonment of Brooks Camp is a unique and fascinating bit of information, but sadly one that is almost unusable. Was the story collected and recorded faithfully by Ivan Petroff? I don’t think we can assume anything beyond that the story corroborates a known period of warfare. Did Ivan Petroff invent a good, short story that he knew would catch people’s attentions? Perhaps.

We don’t know either way, and until either more fieldwork in the archaeology or ethnography brings to light more evidence we will not. For all of his faults, Ivan Petroff was a remarkable man, outdoorsmen, explorer, civil servant, and a survivor of many hardships. Through his work, which I think all can agree was at least tireless, Ivan Petroff brought the first real knowledge of the Katmai country to the rest of the country.

References

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. 1890 The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: Literary Industries. Volume 39. Pp. 270-271. San Francisco, CA: The History Company, Publishers. https://archive.org/stream/cihm_14190#page/n9/mode/2up

Dummond, Don E. 2005 A Naknek Chronicle: Ten Thousand Years in a land of Lakes and Rivers and Mountains of Fire. Pp.72-73. Washington, DC: General Printing Office.

Foster, John W. 1895 Results of the Bering Sea Arbitration. The North American Review 0161(469):696-703. http://bit.ly/1nR8KYb

Petroff, Ivan. 1884 Report on the Population, Industries, and Resources of Alaska. Pp. 24-25. Washington, DC: General Printing Office. http://bit.ly/1E3eoup

Pierce, Richard A. 1968 New Light on Ivan Petroff, Historian of Alaska. The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 59(1):1- 10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40488459

Unknown. A Special Agent's Treachery: False Information Incorporated. New York Times, November 13, 1892.http://nyti.ms/1yIrfz6