In the early 20th century geologists had a limited understanding of volcanoes. Plate tectonic theory was still half a century away. Radio communications in remote, volcanically active areas were unreliable or non-existent. Eyewitness accounts of volcanic eruptions were difficult to gather. Seismographs, an essential tool for contemporary volcanologists, were almost unheard of in Alaska. For many years, little was known or understood about what happened in early June 1912 on the northern Alaska Peninsula.

The Eruption

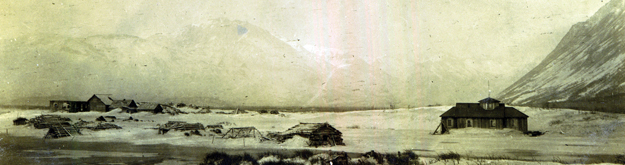

Residents of Katmai Village fled the area in the days leading up to the 1912 eruption. The village was buried under several feet of ash.

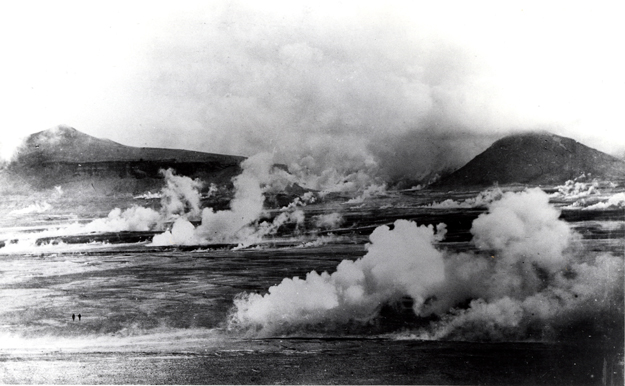

Early Theories Emerge and Give WayThe scale of the eruption attracted explorers seeking to unravel its secrets. Starting in 1915, expeditions sponsored by the National Geographic Society and led by Robert F. Griggs shed light on the eruption and the surrounding region. Griggs and his team surmised that newly beheaded Mount Katmai had exploded and that the steaming valley they discovered (Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes) was underlain by several volcanic fissures. These fissures were the source of a “hot sand flow” which “welled up to fill the Valley itself.” “No one vent,” Griggs wrote in 1922, “could have supplied” all of the ash and pumice filling the Valley. For several decades afterward this was the prevailing theory on the eruption’s mechanisms.

The first explorers into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes thought that it was formed when several volcanic fissures opened under the surface and allowed a hot sand flow to pour out.

In the 1950s, however, a new generation of geologists challenged the Griggs team’s original conclusions. Instead of Mount Katmai exploding, they discovered that the magma underneath Mount Katmai was released through a nearby vent which Griggs had named Novarupta, or “new eruption.” The emptying magma chamber beneath Mount Katmai could no longer support the overlying mountain peak. It collapsed inward, forming a spectacular, lake-filled caldera. Indeed, very little was erupted from Mount Katmai. Essentially all of the ash and pumice which fell on the landscape, including that which created the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, came from the vent at Novarupta.

At least on the surface, the eruption is now well understood and described. However, one secret that geologists are still investigating concerns the “plumbing” between Mt. Katmai and Novarupta. How did the magma stored underneath Mount Katmai get to Novarupta over 6 miles (10 kilometers) away? The lavas of the 1912 eruption may hold the answer.

Three different lavas--rhyolite, dacite, and andesite--erupted from Novarupta. Some of this magma mixed together shortly before and/or during the eruption to create distinctly banded pumice. The mixing happened so quickly, in fact, that the bands are distinct even on a microscopic level.

The striping in this piece of pumice is from different magmas. The darker bands are from andesite. The lighter bands are from dacite.

The banded pumice reveals much about the inner workings of the volcano--the magmas mixed quickly, and the magma underneath Mt. Katmai erupted at Novarupta. But, how was the magma stored under the earth prior to the eruption, and why did it vent at Novarupta? These are questions that still need to be answered.

Theories explaining the mechanisms of the 1912 eruption have changed considerably over time and geologists have gained a firm understanding of the 1912 eruption’s complexity, but mysteries do remain. As the volcanologists Judy Fierstein and Wes Hildreth recently wrote, “The Novarupta-Katmai eruption remains one of the most provocative historic eruptions for many volcanologists.” The volcano has yet to reveal all of its secrets.