Panorama from Pea Soup Pass towards Novarupta. Photo by Anela Ramos.

Panorama from Pea Soup Pass towards Novarupta. Photo by Anela Ramos.

Over Memorial day weekend, rangers embarked on their first trip into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. With training over and the season about to begin, many of us were anxious to take advantage of a rare three day weekend. For all but a few, this was our first time in the valley, and our first time witnessing in person the aftermath of the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century.

We hit the trail early on Saturday morning from the Robert F. Griggs Visitor Center, where willow, grass and tundra has already reclaimed the earth. About a mile away, the vegetation disappears abruptly, and is replaced by fields of pumice and ash, where a new world of color reveals itself. Red, yellow, orange, purple and green stained rock and sand sprawls out towards distant mountain-volcanoes.

View from outside the Robert F. Griggs Visitor Center into the VTTS Photo by Daniel Lombardi.

View from outside the Robert F. Griggs Visitor Center into the VTTS Photo by Daniel Lombardi.

But even here, life is making a living, almost out of nothing. Soil is slowly forming out of sterile ash, moss and lichen and even wildflowers are fanning out from glacial streams and from the hillsides of the Buttress Range. Just one hundred years ago, gas and rock heated to 1,000 degrees Celsius smothered what was then a flourishing valley, and now that same valley - untouched, unaided, and largely unnoticed - is slowly returning to its original state.

Wildflowers blooming in the valley. Photo by Daniel Lombardi.

Wildflowers blooming in the valley. Photo by Daniel Lombardi.

As we made our way through the healing landscape, we did our best to tip toe around budding plants and cryptobiotic soil. Fourteen miles later we reached our first destination: a pair of dilapidated USGS research huts atop Baked Mountain, and rested for the night. The next morning, we traveled over Pea Soup Pass to Novarupta, the source of the 1912 volcanic eruption. Although we had seen bear and wolf tracks, lynx scat, and ground squirrel burrows along the way to Baked Mountain, it wasn’t until we reached the big black lava plug - or the giant back head, as one ranger called it - that I saw any living, breathing animals. A snow bunting chirped and hopped around me as I scrambled up the steep talus walls of Novarupta.

A snow bunting perched on a boulder. Photo by David Kopshever.

A snow bunting perched on a boulder. Photo by David Kopshever.

Sitting on the top of such a massive source of destruction and earth shattering power, I found myself in a quite reflective mood. I recalled that Robert Griggs discovered this place exactly 100 years ago, and later worked to protect it as a National Monument. Without his efforts and passion for this place, Katmai may have never existed as a National Park. Bears likely would not occupy the Brooks River in large numbers as they do today, salmon and trophy trout would not spawn uninterrupted, and this remote, beautiful piece of the planet would not be protected, and remain largely untouched.

Rangers approach Novarupta through a snowfield. Photo by Anela Ramos.

Rangers approach Novarupta through a snowfield. Photo by Anela Ramos.

As I considered this delicate chain of events, I wondered, “Why do we protect these places?” Of course, we can all agree that we should protect places of wilderness and beauty. The National Park Service says that we do so for our “enjoyment, education, and inspiration,” but is there a bigger, more meaningful reason? If we simply protect wilderness so that we can enjoy it, then what makes it any different than an amusement park? I will always be pulled towards wilderness, but I am beginning to think that it should exist for more than the sake of human use. The mountains and rivers, the trees, rocks, bugs, birds and animals - the ingredients to our world, exist beyond our realm of being. The value of these places cannot be quantified, because they are invaluable.

Sunset over the Buttress range. Photo by Daniel Lombardi.

Sunset over the Buttress range. Photo by Daniel Lombardi.

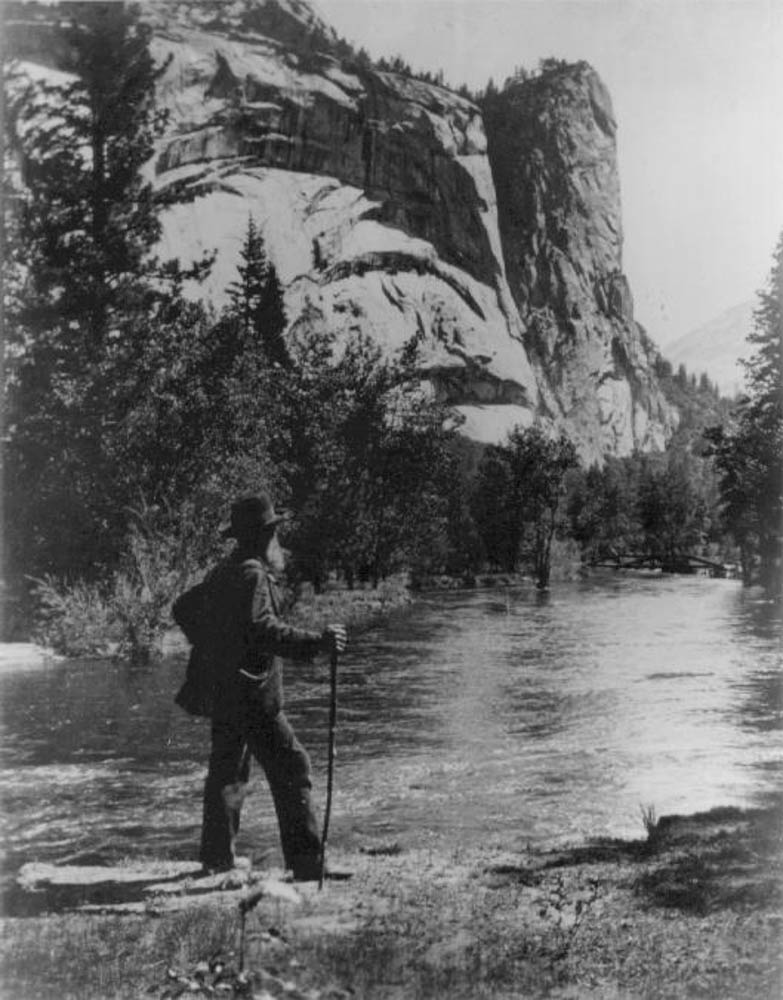

Before our new staff training ended, a quote by John Muir, one of the founding fathers of the National Park Service, was shared with us. He said, “I'll interpret the rocks, learn the language of flood, storm, and the avalanche. I'll acquaint myself with the glaciers and wild gardens, and get as near the heart of the world as I can.”

John Muir overlooking the Merced River. Photo courtesy of Sierra Club.

John Muir overlooking the Merced River. Photo courtesy of Sierra Club.

As I continue to explore this park, at the ends of the earth and the heart of the world, I’ll be listening to the language of Katmai. I will enjoy it, I will learn from it, and I will be inspired by it; but I will also appreciate it as a priceless reminder that we have a duty to protect this planet, for our sake and for its own.