The year 1917 marked the third, out of four total National Geographic Society (NGS) expeditions, that Robert F. Griggs led to explore the area of Katmai; in the aftermath of the massive eruption of the Novarupta volcano which took place on June 6th, 1912. The expedition consisted of a ten-man team, including a chemist, zoologist, topographer, and two botanists. In this year, their expedition would focus specifically on the Valley of 10,000 Smokes.

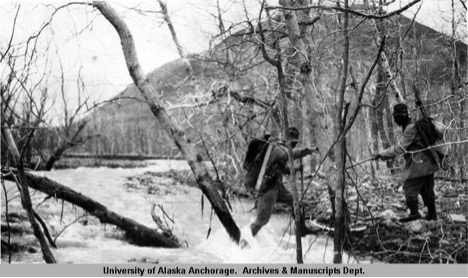

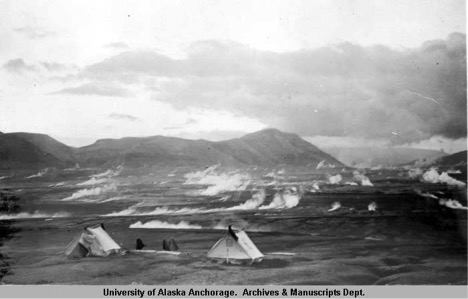

Historic photos from the expeditions give us an idea of the adventures these explorers had.

“Crossing stream in lower Ukak Valley”. National Geographic Society Katmai expeditions photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. Photo: P. Hagelbarger

What they encountered was a spectacular landscape of contradictions: offering the most beautiful views but devoid of any life; the conveniences of fresh water, refrigeration, natural cook stoves and floor heating where no shelter could withstand.

To stay warm, the explorers took advantage of what was around them.

“Looking down the valley from Camp 5”. These tents were described by Griggs as “steam-heated”. National Geographic Society Katmai expeditions photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. Photo: D. B. Church

In 2013, Katmai employee Mike Fitz stumbled upon the remnants of one of these base camps while conducting his own explorations of the Valley. This summer, 2016, our team of archaeologists returned to the site to document it fully. What we encountered on our journey was still a landscape of contradictions, but in a fashion somewhat different from that experienced by Griggs and his team.

Our team of archaeologists, following the footsteps of the explorers, recording their early expedition site. NPS Photo/C. Stevens

Our journey to enter the Valley approached from the opposite direction; during the first three expeditions the NGS team travelled directly from the coast via Katmai Pass. Today, essentially all traffic to the Valley comes from the other direction, the pass having since been repopulated by a dense thicket of alders which few hikers dare to enter.

The journey from the North is also not without its perils, however, and I would like to think that we did get a taste of the challenges faced by the early post-eruption explorers. In traveling to our base camp in the Baked Mountain huts we had to cross two rivers, both deep enough that we determined it best to take off our pants entirely before wading through the rushing, glacier-fed streams. These waters have taken lives before, but fortunately our only casualty was a shoe.

The crossing at the River Lethe, with Mt. Mageik in the background. NPS Photo/L. Stelson

The dramatic volcanic activity witnessed by the NGS explorers has since dissipated significantly. We witnessed the Novarupta crater still emitting a steady stream of steaming gasses, and the remnants of a massive fumerole, but otherwise all was still. For the most part, things in the Valley have been very still. So still, in fact, that cryptobiotic crusts made of cyanobacteria, lichens, bryophytes, fungi and algae have begun to form over much of the surface of the Valley floor. Crusts such as these are typically found in arid, desert-like environments and are extremely slow growing and sensitive to disturbances. Their growth takes a minimum of 45 years on undisturbed surfaces.

Wisps of steam emerging from the Novarupta crater. NPS Photo/L. Stelson

A huge, inactive fumerole encountered next to Baked Mtn. NPS Photo/L. Stelson

While it was easy enough to relocate the camp with our GPS unit, you would never know you were there until you found yourself standing in it. Once on site, we were surprised to find some items apparently undisturbed, as left by their original owners, while other items that had been photographed just three years prior had been moved, or covered up entirely. We soon discovered that the cause of this was the large amounts of sediment still being transported down the slope by the annual snow melt, building up the land in some areas, and cutting drainages into it in others. This truly was a landscape of contradictions.

Artifacts flagged in drainage cutting through the cryptobiotic surface crust, caused by the annual snowmelt traveling down from the Mountain above. NPS Photo/C. Stevens

Not surprisingly, the artifacts we found suggested that the camp’s occupants had done their best to pack lightly. While one of the hallmarks of a historic camp or settler site in the Lower 48 is typically a scattering of old tin cans and bottles from carrying food products, we only encountered one single can here, as well as glassware that was scientific in nature. The team had mostly stuck to eating dry and dehydrated foods, just like modern backpackers, as they had to carry absolutely everything they needed for miles inland from the coast. Anything they would not require for their return was abandoned in the Valley. Interestingly, we found the remnants of one rather fancy looking oxford-style shoe, which we took back with us for further analysis. Take a shoe, leave a shoe. Apparently, this is a rule of the Valley.

Remnants of a shoe discovered at the NGS expedition camp . NPS Photo/C. Stevens

That night, and for the next 36 hours, we would then experience the other face of this strange and unique environment. After two days of warm weather, clear skies, and beautiful views, the winds began to pick up speed dramatically. The sky was cloudy, visibility only 20 feet at times, and rain seeped into our living quarters from every possible crack; but the worst was the wind. It howled and crashed and blasted the cabins with chunks of pumice so hard that the entire structure would shake. If you needed the restroom, you would have to wait and hope for a reasonably calm moment, or find yourself getting blown about. The NGS team experienced these same conditions, only they were forced to stay in tents, which were repeatedly shredded and patched together again. On the fourth and last day of our adventure the skies had cleared again, making for a quick and pleasant hike back out.

All in all, I can only surmise that the NGS expedition team, consisting of Robert F. Griggs, James S. Hine, J. W. Shipley, Clarence F. Maynard, Donovan B. Church, Lucius G. Folsom, Paul R. Hagelbarger, Jasper D. Sayre, Walter Matroken, and Andrean Yagashoff must have been one tough crew.

Find out more through these references:

- Clemens, Janet, and Frank B. Norris. 1999. Building in an ashen land: Katmai National Park and Preserve : historic resource study. Anchorage, Alaska: National Park Service, Alaska Support Office

- Belnap, J., 1993, Recovery rates of cryptobiotic crusts: Inoculant use and assessment methods: Great Basin Naturalist, v. 53, p. 89-95.

- Griggs, R. 1917. "Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes: an account of the discovery and exploration of the most wonderful volcanic region in the world". Natl. Geogr. Mag. 33:2: 115-169.