(NPS/B. Plog)

Before arriving in Katmai National Park and Preserve in May, I had worked two years in the desert of the American Southwest. Perhaps it comes as no surprise then that the first thing I noticed about Katmai was the water. Water infuses all life on the planet, but it seems especially prevalent in Katmai. That the weather, landscape, and geographic features all seem completely reliant on water is something that struck me when I first arrived to Katmai and in the months since. Katmai is surrounded by water from every direction. The park almost completely straddles the Alaskan Peninsula, which juts south and west into the Pacific Ocean. The Shelikof Strait borders the park to the east for almost 500 miles (800 km), while Bristol Bay is only around 22 miles (35 km) from the park’s western boundary.

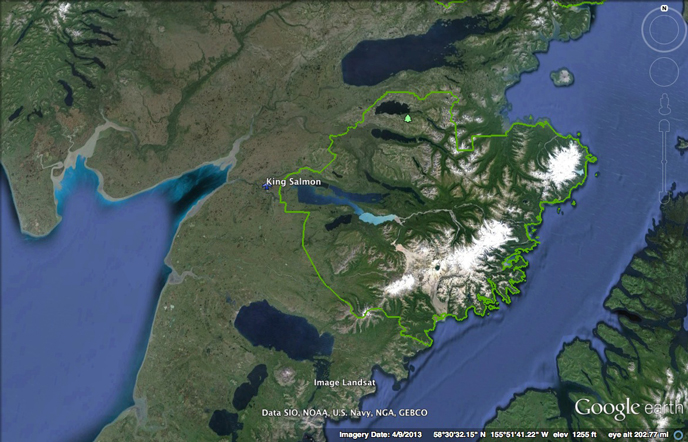

The climate of the northern Alaska Peninsula is heavily influenced by the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Katmai National Park's boundaries are outlined in green. (Google Earth image)

Though I know we’re connected to mainland Alaska, sometimes with the influences of the ocean and the number of lakes and rivers, it feels like Brooks Camp and Katmai are actually part of an island—a very wet island. Rain, ice and snow, lakes and rivers: water, in its many forms, dominants the landscape.

Rain

Rain drips from the needles of the spruce trees and leaves of the alder, willow, and birch that cover the land, keeping the landscape green and lush. Rainwater streams off the roofs of the visitors center, auditorium, and cabins, pouring onto the gravel trails. It drips down my neck off my hat as I walk, beading up on the green of my uniform. It seeps into the thick fur of the brown bears, adding weight to their already chubby frames.

Along the Alaskan coast, the weather is notoriously rainy thanks to the moist air coming off the Pacific. This summer has had its share of damp days when rain pelts us in sheets causing visitors and rangers alike to find any protection from the elements we can. Sometimes the best I can do is pull on rain pants and long for the sun to come out again.

Katmai experiences long bouts with wet weather. (NPS/B. Plog)

The mountains of the Aleutian Range create a rain shadow effect over the western portions of the park. While the Pacific coast of Katmai National Park can experience 40-50 inches (102-157 cm) of precipitation per year, the average yearly precipitation in Brooks Camp is only around 18 inches (46 centimeters). Living here, however, sometimes it can feel like this figure is too low. Recently there have been a number of gray, overcast days in a row and even if it’s not pouring, a light drizzle will permeate everything around.

Needless to say, if you are planning to visit any part of Katmai National Park, a raincoat—and perhaps rain pants—are highly recommended.

Snow and Ice

As part of Alaska, it is no surprise that Katmai has a fair amount of snow and ice. Even as summer approached in early June, snow dusted the tops of the surrounding peaks with late spring coats as if to remind everyone that winter is never far away.

I can look from Brooks Camp and see snow-capped mountains. Mt. Denison, Mt. Griggs, Mt. Mageik, Mt. Katmai, and Trident—the highest peaks in the park—sport snowy tops and sides even in the middle of summer, a result of our northern latitude. These high peaks may receive as much as 100-120 inches (254-305 cm) of precipitation per year.

Mount Mageik is one of the many volcanoes in Katmai that is clad in glaciers. (NPS/B. Plog)

Lakes and Rivers

Surface water in the form of rivers and lakes dominate the landscape. Minnesota may be the Land of 10,000 Lakes, but Katmai National Park and Preserve has nearly as many: 9,257 lakes in all. There are also almost 6,000 miles (9,660 kilometers) of rivers and streams winding their way around mountains and through valleys until eventually emptying into the Pacific Ocean.

These waters make the wilderness of Katmai National Park and Preserve somewhat accessible. If you’ve been to Katmai, how did you get here? I imagine most of you did not walk or ski—and I know for certain you did not drive. Probably like me, you came via a water route. I came, like many visitors, into the park by landing on Naknek Lake, our floatplane causing only brief waves and ripples in this giant body of water.

The turquoise waters of the Iliuk Arm of Naknek Lake are stunning in their color. (NPS/B. Plog)

In contrast, Lake Brooks, 1.2 miles (1.9 kilometers) from the Brooks Camp Visitor Center, is not fed by glaciers and is almost always perfectly clear. It is also noticeably warmer than Naknek Lake, though few seem willing to jump into the two lakes to test the difference.

Connecting Lake Brooks to Naknek Lake is perhaps the most famous body of water in the park: Brooks River. Though it is only 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) long, its rushing waters and pebbled bottom make it perfect salmon habitat. The salmon attract a variety of wildlife, most famously brown bears. I never cease to enjoy watching the red, maroon, and silver bodies of salmon swimming in the river.

Other rivers, such as the Ukak and Lethe, rush and churn through more rugged landscapes. These rivers in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes carve through the hundreds of feet of ash and pumice that burst from the Novarupta volcano in 1912, and have created canyons full of rushing, ashen water.

Ash and pumice from the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes as well as glacially eroded rock and eroded out of the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. (NPS/B. Plog)

Without these lakes and rivers, in their many different forms, what most people think of as Katmai National Park or Brooks Camp would cease to exist.

Always Present

Without water, life on earth could not sustain itself. Without the amount of water and the different forms it takes in Katmai National Park and Preserve, the landscape and life here would be dramatically different and nearly inaccessible.

As the summer quickly passes, I will continue to take in the colors of the lakes, the beauty of the glaciers, and the way the rivers bring life to every corner of the park. With all this water around, can one choose a favorite water feature in the park? Naknek Lake? The Knife Creek Glaciers? Brooks Falls? It is hard for me to decide.

Whichever place I explore next in Katmai, it will probably be shaped by our ever-present water. And so while I may or may not bring my bathing suit, no matter where I go in Katmai, I’ll remember to pack my rain gear.