Adventurer, linguist, collector of antiquities, probable plunderer of historic documents, and the originator of mysterious crystal skulls--all of these descriptions and more can be applied to the nebulous French national Alphonse Pinart.

Adventurer, linguist, collector of antiquities, probable plunderer of historic documents, and the originator of mysterious crystal skulls--all of these descriptions and more can be applied to the nebulous French national Alphonse Pinart.

Undoubtedly a truly gifted academic, Mr. Pinart is connected with Katmai through his early support of the proposition that the native peoples of the Americas originated through their ancestral migrations from Asia. Today this concept is widely accepted, but the academic community was less supportive in the 19th century. Apparently undaunted, and with access to family wealth, nineteen year old Alphonse arrived in Alaska to conduct linguistic work among native peoples, attempting to elucidate the relationship between Siberian and Alaskan languages.

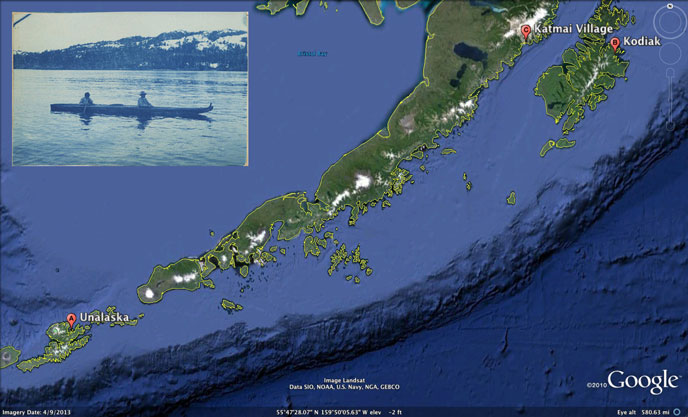

Pinart's interests took him far north into the Bering Sea, but his wide ranging journey by kayak started in Unalaska in the Aleutian Islands. From Unalaska, he paddled roughly northwest along the southern coast of the Alaska Peninsula. He spent the winter of 1872-1873 paddling among the Alutiiq villages near Kodiak, collecting words and artifacts from the residents. This travel by kayak eventually brought the young anthropologist to the village of Katmai, on the Shelikof Strait coast of the present park.![]()

![]()

To travel just from Unalaska to Kodiak by air today is a distance of over 600 miles, so one can imagine how mammoth of an undertaking this was in a skin kayak in the open ocean! Map courtesy of Google Earth. Inset photo courtesy of Edwin F. Glenn papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage.

The world Pinart paddled through was one of flux and change. Just four years earlier the entire territory of Alaska was still under Russian control, but the American purchase was beginning to fundamentally transform the native peoples. Gone was the all-pervasive administration of the Russian American Company, along with their restrictive wildlife conservation policies and invasive scheduling of the lives of native villagers. The American regime was much more relaxed, even to the point of abandonment.

Just four years earlier the entire territory of Alaska was still under Russian control, but the American purchase was beginning to fundamentally transform the native peoples. Gone was the all-pervasive administration of the Russian American Company, along with their restrictive wildlife conservation policies and invasive scheduling of the lives of native villagers. The American regime was much more relaxed, even to the point of abandonment.

After the Alaska Purchase in 1867, times were good for hunters until the sea otter population, now bereft of any protection, crashed. Sea otters were almost entirely extirpated by 1911. Poverty, social disintegration, and the migration to wage jobs based largely around commercial fishing followed the crash of the otter population. The new poverty was combined with a repressive school system that punished native culture. The boundaries of cultural identity and traditional knowledge were blurred and sometimes lost.

The world that Pinart guided his kayak through was in the process of this change. Many villagers he interviewed were probably bilingual in Russian and Alutiiq, with the pressures for learning English still growing. Some villages maintained their traditional winter dances, and the teen-aged Alphonse was one of the last outsiders to witness this ceremonial tradition before it was largely lost through assimilation. As part of Alphonse Pinart's research, he collected ceremonial masks used from the dances, and the at least 70 masks he carefully packaged and sent home are unique. These masks were given to two museums in France, and are indisputably the finest collection of Alutiiq masks in the world. Carved by hand, some with the aid of beaver tooth tools, the Pinart collection of masks represent the last ceremonial masks created under the ancient arrangement of Alutiiq apprentice and master.

The masks Pinart collected still exist, and can be seen on display in France. In 2008 thirty four of Pinart's masks were temporarily displayed back in Alaska, on the island of Kodiak. For the first time Alutiiq descendents could view the definitive work of their ancestors, forging another link back to old traditions. Photos © Boulogne-sur-Mer, Château-Musée, © Direction des Musées de France.

Alphonse Pinart went on to many other adventures. The period that included Alaska continued for almost eighteen years straight, as Pinart was involved in Mexico, Canada, California, New Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, Russia, Oceania and Germany. A gifted linguist, Alphonse Pinart studied Maya, Nahuatl (Aztec), German, English, Spanish, Sanskrit, Chinese, Latin, Russian and Vietnamese, and was interested in the many others he experienced first-hand. A former employer of his, Hubert Howe Bancroft, claimed that Mr. Pinart was knowledgeable in fifty (50!) native languages.

The adventure of paddling along the Alaskan coast was a defining moment in Pinart's life, one that he referred to on numerous occasions, and one he wished to revisit. The wide ranging adventures would be the envy of any global traveler, while I imagine that his linguistic gifts were and are the envy of almost any philologist.

All these accomplishments were tempered by darker rumors that I found in my brief research. In 1877 Alphonse Pinart was involved on an expedition to study the prehistory and history of California. Undertaken under the auspices of the Department of Instruction, apparently much of the funding was actually provided by Pinart himself. Pinart's research partner in the venture, Leon De Cessac, set up his operations in San Luis de Obispo, conducting fieldwork and becoming engaged to a local woman, Cen Dilladet. For unknown reasons Pinart apparently abandoned the whole project, heading out to Oceania instead. Leon de Cessac, now left in a dire financial position, was forced to travel back to France never to return. De Cessac would die some fourteen years later penniless, while his beloved Cen never married.

The Spanish Archives of Santa Fe, New Mexico note that Mr. Pinart outright stole significant 18th century documents that were later incorporated into the Hubert Howe Bancroft Collection, now housed at the University of California, Berkeley. A different interpretation is provided by a publication of the Bancroft Collection, which states that these important documents were “salvaged” by Mr. Pinart after a “governmental blunder” scattered the old Spanish archive in 1870. If this was in fact what occurred, I am surprised that not more of the archive's materials were not actually scattered in this period to other collections.

Sadly even the crystal skulls that Pinart collected are of dubious authenticity. Purchased from a sometimes fraudulent antiquities dealer named Eugene Boban in 1875, Pinart later donated the three crystal skulls of purported prehistoric Meso-American origin to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadero, now the Musee de l’Homme. This donation included many other objects collected by Boban, and placed the museum's American collection as one of the finest in all of Europe at the time. Academia is now united in its assertion that the crystal skulls are nothing more than clever 18th century forgeries, but many of the other donated objects are spectacular artifacts. Apparently in return for donating this noted collection, the French government agreed to sponsor Alphonse Pinart's expeditions overseas. Did Alphonse know or suspect that these skulls were fakes? I do not know.

This theme of the furthering of human understanding combined with some of the less savory elements of the human condition are common enough occurrences in human history. Another noted linguist and explorer who can be described similarly, Ivan Petroff, made his own mark on our understanding of Katmai. Perhaps it should not be surprising that Mr. Petroff was also connected to Alphonse Pinart socially? Find out more in an post next week.

References:

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. 1890. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: Literary Industries. Volume 39. Pp. 270-271. San Francisco, CA: The History Company, Publishers. https://archive.org/stream/cihm_14190#page/n9/mode/2up

Dummond, Don E. 2005. A Naknek Chronicle: Ten Thousand Years in a land of Lakes and Rivers and Mountains of Fire. Pp.72-73. Washington, DC: General Printing Office.

Laronde, Anne-Claire. 2009. “The Atypical History of Collector Alphonse Pinart (1852-1911) and the Sugpiaq Masks of Boulogne-sur-Mer in France”. In Giinaquq Like a Face: Sugpiaq Masks of the Kodiak Archipelago. Sven D. Haakanson, Jr. and Amy F. Steffian, eds. Pp. 31-35. Fairbanks, AK: Universiy of Alaska Press. http://bit.ly/1tDKae1

Agence France-Presse. 2008. Museum admits real-life Indiana Jones handed over a dud 'relic' 130 years ago. National Post, April 19. http://bit.ly/1yIoMVm

Dallidet Adobe and Gardens. N.d. Historic Adobe. Dallidet Adobe and Gardens. http://dallidet.org/historic.html

Golla,Victor. 2011 California Indian Languages. Page 31. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. http://bit.ly/1wFSusW

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson. 1914. The Spanish Archives of New Mexico. Pp. 213-24. Cedar Rapids, IA: The Torch Press. https://archive.org/details/spanisharchiveso02twituoft