The abundant coastal and intertidal ecosystems on Katmai’s coast provide a substantial nutritional resource for brown bears. We know bears love to munch on shellfish, but we don’t know how critical these food resources are for them. Are the clams, mussels, and sedges of the spring as beneficial as the salmon they eat in the fall? Does increasing visitation to the coast affect the way bears use these resources? Are bears in trouble if the mussels and clams are damaged by oil spills or ocean acidification? These are just some of the questions that the Changing Tides project is hoping to address. With one year of field work completed in 2015, there are no clear answers yet, but there are some intriguing results.

The Changing Tides Project is a three-year study to investigate the linkages between marine and terrestrial organisms, specifically looking at the connection between intertidal invertebrates (such as clams and mussels), brown bears, and people. This study will help everyone, from visitors to resource managers; minimize their impact to the resources on Katmai’s coast.

Will an increase of visitation to the coast affect the bears that live there? A collared bear is photographed in close proximity to visitors. J. Erlenbach photo.

Will an increase of visitation to the coast affect the bears that live there? A collared bear is photographed in close proximity to visitors. J. Erlenbach photo.

The Changing Tides project works to understand how important the intertidal and nearshore region is for bears, like this sow and cubs at Hallo Bay. J. Erlenbach photo.

The Changing Tides project works to understand how important the intertidal and nearshore region is for bears, like this sow and cubs at Hallo Bay. J. Erlenbach photo.

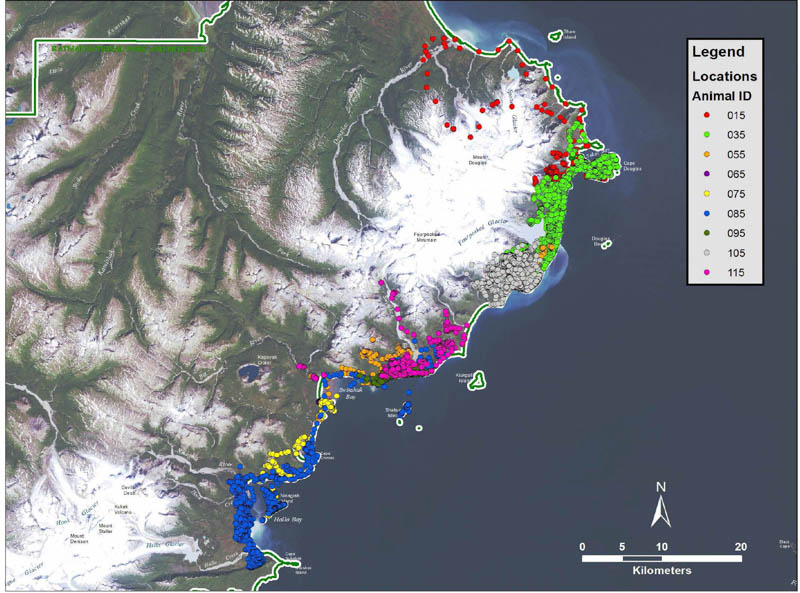

Last year nine female bears, none with first year cubs, were GPS collared in May, allowing researcher to track them and see which habitats they spend the most time in. Two of the collars were equipped with video cameras, which collected one minute of video every 10 minutes. These cameras help reveal what the bears are doing when they are in particular habitats and can help answer questions like; how much of a clam does a bear eat, which mussels does they prefer, how many bites of sedge do they take in a feeding session? The collars also revealed that these coastal bears seem to occupy relatively small areas, within 3.5 miles of the coast.

Movement from the nine GPS collars in 2015, each color represents a different bear. The bears traveled between 5-22 miles along the coast.

Movement from the nine GPS collars in 2015, each color represents a different bear. The bears traveled between 5-22 miles along the coast.

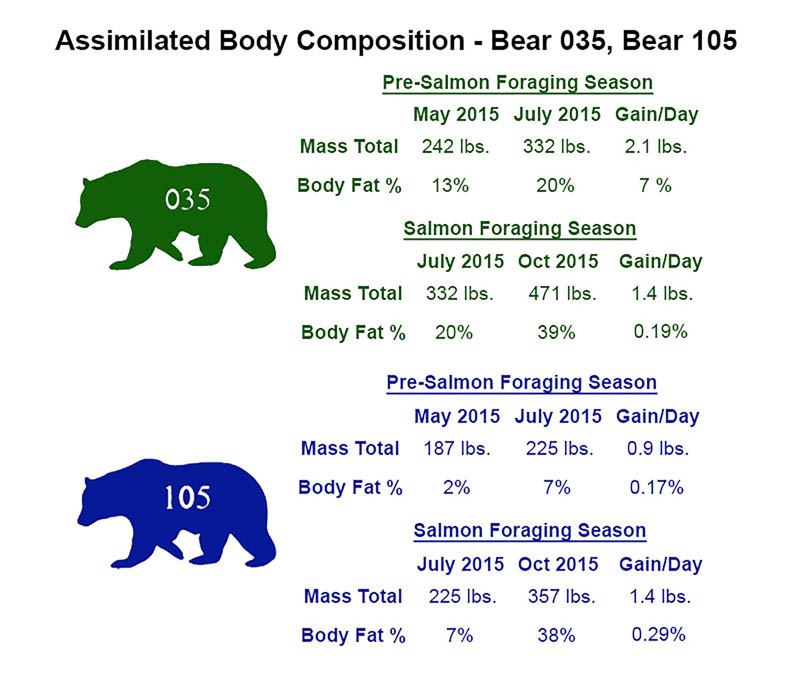

In order to better understand bear diets, the researchers hoped to capture each bear in the spring, summer and fall to take measurements and samples. Each bear would be weighed, measured, and a blood and hair sample would be taken. These measurements and samples are used to evaluate the changes in body composition throughout the summer season. Comparing the body compositions of the bears for the pre-salmon foraging season (May-July) to the salmon foraging season (July-October) could help shed light on the relative importance of intertidal food resources. Chemical markers in the blood and hair samples can be traced to food sources, and help create a picture of what the bears are eating. Springtime resources available to bears, especially females with young, can shape its development, susceptibility to disease, and their ability to reproduce.

Which resources are the most nutritious for a growing bear? A mother bear rests while her cub plays on a log in the sedge meadows of Hallo Bay. J. Erlenbach photo

Which resources are the most nutritious for a growing bear? A mother bear rests while her cub plays on a log in the sedge meadows of Hallo Bay. J. Erlenbach photo

In July 2015, just six of the bears were recaptured for sampling. Of the three that weren’t recaptured, one collar had dropped, and two bears were in Hallo Bay close to visitors so researchers chose not to disturb the bears or visitors. During this period between late May and early July, the bears gained significant mass, averaging 77 pounds (lbs.) for the season or 1.9 pounds a day. Of course, each bear is different and the range of weight gain was from 11-141 pounds. Bear 095 gained 140 pounds while caring for three yearlings! That is an average of 3.4 pounds a day! From observational data scans we learned that the sedge areas were used by both sexes equally in the pre-salmon season.

From last year’s observational scans, researchers saw that most of the intertidal foraging was for clams during the pre-salmon season. J. Erlenbach Photo.

From last year’s observational scans, researchers saw that most of the intertidal foraging was for clams during the pre-salmon season. J. Erlenbach Photo.

In October 2015, six bears were again recaptured, but only two were bears that were recaptured in July. This means that for the span of the season, we only have two bears with which we can compare the weight gain, body composition, and chemical markers of the diet. From these two bears we have learned that they gained less mass during the salmon season than during the pre-salmon foraging season, about 1.4 pounds a day. These two bears did, however, gain more body fat from salmon at about 25.5% gain compared to the 5% gain in the pre-salmon season.

Does this tell us that the intertidal resources are helpful for gaining muscle mass after hibernation? Can we assume that the bears switch from the intertidal to salmon to help increase the fat intake before hibernation? Since we only have two individual bears to compare at this point, it is not safe to create any conclusions yet. However, it does spur the curiosity in us all. Will this year’s findings support our current understanding, or will new findings suggest a different theory?

We’ll have an update on the first capture of bears for 2016 next week. Be sure to check back!

Explore some of the data that was collected yourself on our new Changing Tides Story Map!

J. Erlenbach Photo.

J. Erlenbach Photo.

Find out more about the Changing Tides Project.

If you have any questions or would like more information on this project, please contact:

Carissa Turner, Coastal BiologistKatmai National Park, King Salmon, AK (907) 246-2104, carissa_n_turner@nps.gov

Kaitlyn Kunce, Science CommunicatorKatmai National Park, King Salmon, AK (907) 246-2129, kaitlyn_kunce@nps.gov