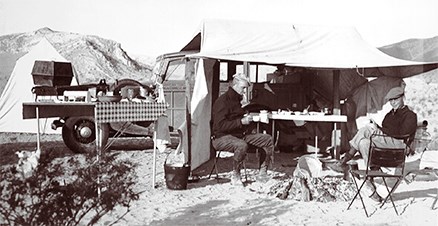

Campbell’s work revolutionized theories on early desert cultures. Campbell photo, JOTR 9960

Elizabeth Warder Crozer was born in August of 1893 into a well-to-do society where families lived in mansions flanked by lawns, gardens, and private woods. She was schooled at home by a French tutor until age fourteen, when she entered a Philadelphia women's finishing school where the headmistress prepared her students for a college education rather than the more common entrance into society and marriage. It was her last formal education, except for the nurse's training she received during World War I. Late in the war, she met William (Bill) Henry Campbell, a military ambulance driver, at the wedding of a friend. After rejoining his unit on the Italian front, Bill was exposed to mustard gas, which burned his lungs and required an extended convalescence in the hospital. Despite the disapproval of her family, Bill and Elizabeth married in 1920, leaving Elizabeth to believe that she had been disowned and removed from any inheritance. Bill's failing health brought them across the country to Pasadena, California and later to Twentynine Palms, where his doctor believed the dry desert air would help heal his lungs. Housing in Twentynine Palms was scarce and in 1925 Elizabeth found herself living in a tent pitched at the Oasis of Mara, looking out over the southern California desert for the first time. Bill's health noticeably improved after camping at the oasis for several weeks so they decided to homestead in the area. Joining the small number of early residents of Twentynine Palms, California, the Campbells built a small house which Elizabeth described as "a one car garage with a window on each side." When Elizabeth's father died in 1926, she discovered that he had established a trust fund for her which supported her comfortably for the rest of her life. The small wooden house would later become the kitchen attached to a very large stone house. The trust fund also enabled both the Campbells to take an active role in the development of the community of Twentynine Palms and their new avocation-desert archeology.

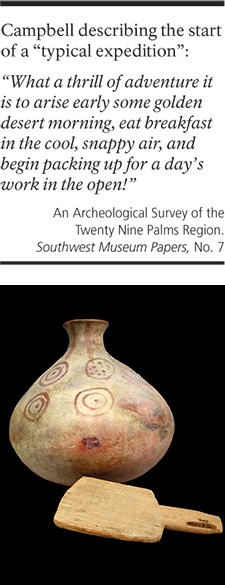

Desert Archeology Recognizing that road improvements were bringing more homesteaders and visitors to the area and increasing the likelihood of damage to archeological sites, the Campbells contacted the Southwest Museum in Pasadena for advice and information. They began working regularly with well known archeologists Charles Amsden and Edwin Walker, and quickly began to publish their findings. Although her earliest papers were short, amateurish accounts of archaeological discoveries, they soon evolved into substantive papers that contributed to the development of regional prehistory theory. Between 1929 and 1940 Elizabeth was the author or senior author of six articles and three monographs. Her monograph, "An Archaeological Survey of the Twenty Nine Palms Region" (Campbell 1931), was one of the first intensive surveys of the region, in part based on the information provided by Bill McHaney. In 1932 the Desert Branch of the Southwest Museum was established in Twentynine Palms in an outbuilding on the Campbells' property. Elizabeth did the writing and most of the lab work while William did the mapping and dealt with the equipment, logistics, and transportation. Pinto Basin Site Collaborating with geologist David Schraf and paleontologist Chester Stock from the California Institute of Technology, the Campbells began field work in the Pinto Basin in 1933. They discovered a heavy concentration of archeological surface sites along six miles of an ancient, dry-stream channel. Since no springs were in the vicinity, the association of the sites with the dry channel led them to conclude that those sites must be associated with an ancient river or stream that flowed sometime in the late Pleistocene or early Holocene. From the Pinto site, and later work at the north end of Pleistocene Lake Mojave beginning in 1934, Elizabeth came to recognize a relationship between humans and environmental factors that could influence settlement patterns. In the spring of 1936, the new professional journal American Antiquity published her paper "Archaeological Problems in the Southern California Deserts." A Revolutionary Approach Mainstream American archeology of the 1920s and 30s was rooted in the examination of prehistoric technological development. Elizabeth Campbell's approach to archeology was outside that mainstream. Essential to her theoretical model is a relationship between prehistoric humans and their changing physical environment, especially water in the desert. Today Elizabeth's work appears so fundamental as to be unexciting, but during her lifetime her theories must have appeared experimental and unproven. The Campbells legacy includes field notes, photographs, and site notations along with thousands of well documented artifacts curated at Joshua Tree National Park and the Autry National Center in Los Angeles. The information above was adapted from a paper by Claude N. Warren, Prof Emeritus, University of Nevada, Las Vegas. |

Last updated: February 15, 2023