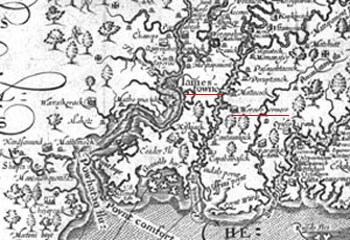

John Smith's Map of 1612 Not much is known about this memorable woman. What we do know was written by others, as none of her thoughts or feelings were ever recorded. Specifically, her story has been told through written historical accounts and, most recently, through the sacred oral history of the Mattaponi. Most notably, Pocahontas has left an indelible impression that has endured for more than 400 years. And yet, many people who know her name do not know much about her. The Written History Pocahontas was born about 1596 and named "Amonute," though she also had a more private name of Matoaka. She was called "Pocahontas" as a nickname, which meant "playful one," because of her frolicsome and curious nature. She was the daughter of Wahunsenaca (Chief Powhatan), the mamanatowick (paramount chief) of the Powhatan Chiefdom. At its height, the Powhatan Chiefdom had a population of about 25,000 and included more than 30 Algonquian speaking tribes - each with its own werowance (chief). The Powhatan Indians called their homeland "Tsenacomoco." As the daughter of the paramount chief Powhatan, custom dictated that Pocahontas would have accompanied her mother, who would have gone to live in another village, after her birth (Powhatan still cared for them). However, nothing is written by the English about Pocahontas' mother. Some historians have theorized that she died during childbirth, so it is possible that Pocahontas did not leave like most of her half-siblings. Either way, Pocahontas would have eventually returned to live with her father Powhatan and her half-siblings once she was weaned. Her mother, if still living, would then have been free to remarry.

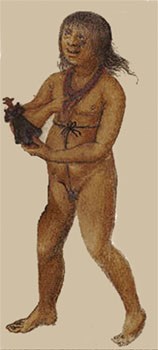

Unknown British Museum As a young girl, Pocahontas would have worn little to no clothing and had her hair shaven except for a small section in the back that was grown out long and usually braided. The shaven parts were probably bristly most of the time as the Powhatan Indians used mussel shells for shaving. In winter, she could have worn a deerskin mantle (not everyone could afford one). As she grew, she would have been taught women's work; even though the favorite daughter of the paramount chief Powhatan afforded her a more privileged lifestyle and more protection, she still needed to know how to be an adult woman. Women's work was separate from men's work, but both were equally taxing and equally important as both benefited all Powhatan society. As Pocahontas would learn, besides bearing and rearing children, women were responsible for building the houses (called yehakins by the Powhatan), which they may have owned. Women did all the farming, (planting and harvesting), the cooking (preparing and serving), collected water needed to cook and drink, gathered firewood for the fires (which women kept going all the time), made mats for houses (inside and out), made baskets, pots, cordage, wooden spoons, platters and mortars. Women were also barbers for the men and would process any meat the men brought home as well as tanning hides to make clothing. Another important thing Pocahontas had to learn to be an adult woman was how to collect edible plants. As a result, she would need to identify the various kinds of useful plants and have the ability to recognize them in all seasons. All of the skills it took to be an adult woman Pocahontas would have learned by the time she was about thirteen, which was the average age Powhatan women reached puberty.

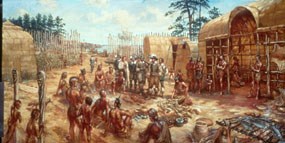

Unknown Artist When the English arrived and settled Jamestown in May 1607, Pocahontas was about eleven years old. Pocahontas and her father would not meet any Englishmen until the winter of 1607, when Captain John Smith (who is perhaps as famous as Pocahontas) was captured by Powhatan's brother Opechancanough. Once captured, Smith was displayed at several Powhatan Indian towns before being brought to the capital of the Powhatan Chiefdom, Werowocomoco, to Chief Powhatan.

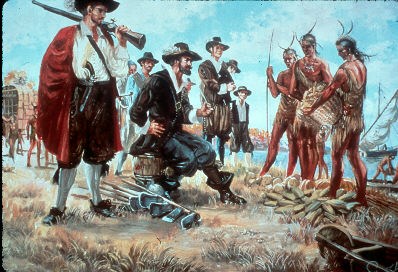

NPS Image By the winter of 1608-1609, the English visited various Powhatan tribes to trade beads and other trinkets for more corn, only to find a severe drought had drastically reduced the tribes' harvests. In addition, Powhatan's official policy for his chiefdom was to cease trading with the English. The settlers were demanding more food than his people had to spare, so the English were threatening the tribes and burning towns to get it. Chief Powhatan sent a message to John Smith, telling him if he brought to Werowocomoco swords, guns, hens, copper, beads, and a grindstone, he would have Smith's ship loaded with corn. Smith and his men visited Powhatan to make the exchange, and ended up stranding their barge. Negotiations did not go well. Powhatan excused himself, then he and his family, including Pocahontas, departed into the woods, unbeknownst to Smith and his men. According to Smith, that night Pocahontas returned to warn him that her father intended to kill him. Smith had already suspected something was wrong, but was still grateful that Pocahontas was willing to risk her life to save his yet again. Afterwards, she disappeared into the woods, never to see Smith in Virginia again. As relations between the two peoples deteriorated, Chief Powhatan, wearied of the constant English demand for food, moved his capital from Werowocomoco (on the York River) in 1609 to Orapaks (on the Chickahominy River), further inland. Pocahontas was not allowed to visit Jamestown anymore. In the fall of 1609 Smith left Virginia because of a severe gunpowder wound. Pocahontas and Powhatan were told that Smith died on the way back to England.

Unknown British Museum The years 1609-1610 would be important ones for Pocahontas. Pocahontas, who was about fourteen, had reached adulthood and marriageable age. She began to dress like a Powhatan woman, wearing a deerskin apron and a leather mantle in winter, since she was of high status. She might also wear one-shouldered fringed deerskin dresses when encountering visitors. Pocahontas started decorating her skin with tattoos. When she traveled in the woods, she would have worn leggings and a breechclout to protect against scratches, as they could become easily infected. She would have also grown her hair out and worn it in a variety of ways: loose, braided into one plait with bangs, or, once married, cut short the same length all around. For the next several years, Pocahontas was not mentioned in the English accounts. In 1613, that changed when Captain Samuel Argall discovered she was living with the Patawomeck. Argall knew relations between the English and the Powhatan Indians were still poor. Capturing Pocahontas could give him the leverage he needed to change that. Argall met with Iopassus, chief of the town of Passapatanzy and brother to the Patawomeck tribe's chief, to help him kidnap Pocahontas. At first, the chief declined, knowing Powhatan would punish the Patawomeck people. Ultimately, the Patawomeck decided to cooperate with Argall; they could tell Powhatan they acted under coercion. The trap was set. During her religious instruction, Pocahontas met widower John Rolfe, who would become famous for introducing the cash crop tobacco to the settlers in Virginia. By all English accounts, the two fell in love and wanted to marry. (Perhaps, once Pocahontas was kidnapped, Kocoum, her first husband, realized divorce was inevitable (there was a form of divorce in Powhatan society). Once Powhatan was sent word that Pocahontas and Rolfe wanted to marry, his people would have considered Pocahontas and Kocoum divorced.) Powhatan consented to the proposed marriage and sent an uncle of Pocahontas' to represent him and her people at the wedding.

Unknown British Museum The Rolfe family traveled to England in 1616, their expenses paid by the Virginia Company of London. Pocahontas, known as "Lady Rebecca Rolfe," was also accompanied by about a dozen Powhatan men and women. Once in England, the party toured the country. Pocahontas attended a masque where she sat near King James I and Queen Anne. Eventually, the Rolfe family moved to rural Brentford, where Pocahontas would again encounter Captain John Smith.

Angela L. Daniel "Silver Star" The Oral History

Sarah J Stebbins The most famous event of Pocahontas' life, her rescue of Captain John Smith, did not happen the way he wrote it. Smith was exploring when he encountered a Powhatan hunting party. A fight ensued, and Smith was captured by Opechancanough. Opechancanough, a younger brother of Wahunsenaca, took Smith from village to village to demonstrate to the Powhatan people that Smith, in particular, and the English, in general, were as human as they were. The "rescue" was a ceremony, initiating Smith as another chief. It was a way to welcome Smith, and, by extension, all the English, into the Powhatan nation. It was an important ceremony, so the quiakros would have played an integral role.

NPS Image Over time, relations between the Powhatan Indians and the English began to deteriorate. The settlers were aggressively demanding food that, due to summer droughts, could not be provided. In January 1609, Captain John Smith paid an uninvited visit to Werowocomoco. Wahunsenaca reprimanded Smith for English conduct, in general, and for Smith's own, in particular. He also expressed his desire for peace with the English. Wahunsenaca followed the Powhatan philosophy of gaining more through peaceful and respectful means than through war and force. According to Smith, during this visit Pocahontas again saved his life by running through the woods that night to warn him her father intended to kill him. However, as in 1607, Smith's life was not in danger. Pocahontas was still a child, and a very well protected and supervised one; it is unlikely she would have been able to provide such a warning. It would have gone against Powhatan cultural standards for children. If Wahunsenaca truly intended to kill Smith, Pocahontas could not have gotten past Smith's guards, let alone prevented his death. As relations continued to worsen between the two peoples, Pocahontas stopped visiting, but the English did not forget her. Pocahontas had her coming of age ceremony, which symbolized that she was eligible for courtship and marriage. This ceremony took place annually and boys and girls aged twelve to fourteen took part. Pocahontas' coming of age ceremony (called a huskanasquaw for girls) took place once she began to show signs of womanhood. Since her mother was dead, her older sister Mattachanna oversaw the huskanasquaw, during which Wahunsenaca's daughter officially changed her name to Pocahontas. The ceremony itself was performed discreetly and more secretly than usual because the quiakros had heard rumors the English planned to kidnap Pocahontas.

NPS Image Rumors of the English wanting to kidnap Pocahontas resurfaced, so she and Kocoum moved to his home village. While there, Pocahontas gave birth to a son. Then, in 1613, the long suspected English plan to kidnap Pocahontas was carried out. Captain Samuel Argall demanded the help of Chief Japazaw. A council was held with the quiakros, while word was sent to Wahunsenaca. Japazaw did not want to give Pocahontas to Argall; she was his sister-in-law. However, not agreeing would have meant certain attack by a relentless Argall, an attack for which Japazaw's people could offer no real defense. Japazaw finally chose the lesser of two evils and agreed to Argall's plan, for the good of the tribe. To gain the Captain's sympathy and possible aid, Japazaw said he feared retaliation from Wahunsenaca. Argall promised his protection and assured the chief that no harm would come to Pocahontas. Before agreeing, Japazaw made a further bargain with Argall: the captain was to release Pocahontas soon after she was brought aboard ship. Argall agreed. Japazaw's wife was sent to get Pocahontas. Once Pocahontas was aboard, Argall broke his word and would not release her. Argall handed a copper kettle to Japazaw and his wife for their "help" and as a way to implicate them in the betrayal. A devastating blow had been dealt to Wahunsenaca and he fell into a deep depression. The quiakros advised retaliation. But, Wahunsenaca refused. Ingrained cultural guidelines stressed peaceful solutions; besides he did not wish to risk Pocahontas being harmed. He felt compelled to choose the path that best ensured his daughter's safety. In the spring of 1614, the English continued to prove to Pocahontas that her father did not love her. They staged an exchange of Pocahontas for her ransom payment (actually the second such payment). During the exchange, a fight broke out and negotiations were terminated by both sides. Pocahontas was told this "refusal" to pay her ransom proved her father loved English weapons more than he loved her. In 1616, the Rolfes and several Powhatan representatives, including Mattachanna and her husband Uttamattamakin, were sent to England. Several of these representatives were actually quiakros in disguise. By March 1617, the family was ready to return to Virginia after a successful tour arranged to gain English interest in Jamestown. While on the ship Pocahontas and her husband dined with Captain Argall. Shortly after, Pocahontas became very ill and began convulsing. Mattachanna ran to get Rolfe for help. When they returned, Pocahontas was dead. She was taken to Gravesend and buried in its church. Young Thomas was left behind to be raised by relatives in England, while the rest of the party sailed back to Virginia.

Sarah J Stebbins Conclusion What little we know about Pocahontas covers only about half of her short life and yet has inspired a myriad of books, poems, paintings, plays, sculptures, and films. It has captured the imagination of people of all ages and backgrounds, scholars and non-scholars alike. The truth of Pocahontas' life is shrouded in interpretation of both the oral and written accounts, which can contradict one another. One thing can be stated with certainty: her story has fascinated people for more than four centuries and it still inspires people today. It will undoubtedly continue to do so. She also still lives on through her own people, who are still here today, and through the descendents of her two sons. Author's note: There are various spellings for the names of people, places and tribes. In this paper I have endeavored to use one spelling throughout, unless otherwise noted. Bibliography Custalow, Dr. Linwood "Little Bear" and Angela L. Daniel "Silver Star." The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Golden: Fulcrum Publishing, 2007. Haile, Edward Wright (editor) Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony: The First Decade: 1607-1617. Chaplain: Roundhouse, 1998. Mossiker, Frances. Pocahontas: The Life and The Legend. New York: Da Capo Press, 1976. Rountree, Helen C. and E. Randolph Turner III. Before and After Jamestown: Virginia's Powhatans and Their Predecessors. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1989. Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005. Rountree, Helen C. The Powhatan Indians of Virginia: Their Traditional Culture. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989. Towsned, Camilla. Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma: The American Portrait Series. New York: Hill And Wang, 2004.

Sarah J Stebbins NPS Seasonal, August 2010

Available online through the National Park Service is A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: THE FIRST CENTURY by Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, Ph.D. |

Last updated: September 4, 2022