NPS image

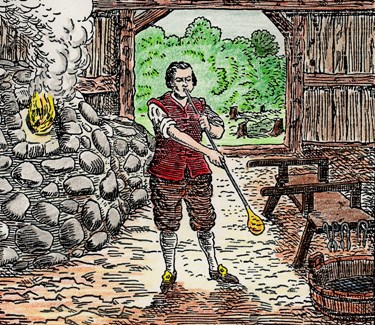

Glassmaking in America began at Jamestown, Virginia in 1608, where a glass factory was operating just a little more than a year after the first colonists arrived from England. The "tryal of glasse" sent back to England that year was not only the first glass made by Englishmen in the New World, but was also their first factory-made product. Businessmen in England made up the London Company. With a new continent to draw upon, they hoped to find valuable raw materials needed back home. They also hoped to manufacture goods that could be sold for a profit. One of the possible industries for which Virginia seemed suitable was glassmaking. In the past 50 years, there had been a great increase in the demand for glass, but this demand could not be satisfied by the English factories. Few Englishmen were skilled in the craft, and though foreign glassmakers had come from the continent to practice their trade and had presumably trained some Englishmen, a great deal of glass was still being imported. Expansion of the industry had been limited by the gradual depletion of the forests, for coal was just beginning to be used in furnaces. Captain Newport had explored the vicinity of Jamestown and would have known that the resources needed for glassmaking were readily available in the new land. The officials of the London Company had every reason to believe glassmaking in Virginia was entirely feasible and a likely source of profit. It seemed reasonable to assume that the cost of glass from a factory in Virginia would be much less than what was being paid in Italy and other continental glass centers. But enlisting English glassmakers to leave a flourishing industry at home and set up business in a strange land across the ocean was not easy. Therefore, the Company looked abroad, and among the 70 settlers who sailed for Virginia in the summer of 1608 were "eight Dutchmen and Poles," some of whom were glassmakers. The so-called Dutchmen probably came from Germany, for Captain John Smith in one of his letters mentions that the London Company had sent to Germany and Poland for "glasse-men and the rest," "the rest" referring to the makers of pitch, tar, soap ashes and clapboard. It was also customary to refer to Germans as "Dutchmen." The introduction of glassmaking in the fall of 1608 appeared at the time to increase the chances for the colony's success. The glass factory, according to Smith was located "in the woods neare a myle from James Towne" or, as William Strachey described it, "a little without the Island where Jamestown stands." There, as Strachey wrote, the glass workers and their helpers erected a glasshouse, which was "a goodly howse...with all offices and furnaces thereto belonging." When Captain Newport left for England later that year, he carried with him "tryals of Pitch, Tarre, Glasse, Frankincense, Sope Ashes; with that Clapboard and Waynscot that could be provided." Of what this first "tryal of glasse" consisted, the records do not tell. The records do indicate that there was some activity at the glass factory during the first six months or so following its establishment. Twelve years later a second glassmaking venture was started at Jamestown. Well planned, reasonably well financed, and staffed with experienced Italian glass workers, it appeared to have a much better chance of success than the earlier venture. This second venture was organized largely through the initiative of Captain William Norton. In June 1621, he petitioned the London Company for a patent to "sett upp a Glasse furnace and make all manner of Beads & Glasse."He proposed to take four "Itallyans" and two servants to Virginia, who were to have the glasshouse operating within three months after their arrival. They sailed for Jamestown in August 1621. The Italians proved difficult for the English to work with, and there were other difficulties. First the glasshouse blew down and then the Indian uprising of 1622 put a stop to everything for the time being. Finally, Captain Norton died, and the Italians "fell extremely sick." George Sandys, resident treasurer for the Company, took over the project upon Norton's death, but fared little better in getting results. He repaired the furnace and the crew set to work in earnest in the spring of 1623, but without success. In a desperate effort to make something of the enterprise, Sandys even sent to England for sand that might better suit the glass workers, but he finally was forced to give up completely in the spring of 1624. The records suggest that little, if any, glass was made during this second and last glassmaking venture at Jamestown. Archaeological excavations did not disclose what kinds of glass were made at Jamestown during the two ventures. When the glasshouse site was excavated in 1948 only small, dark green fragments and drippings were found. Experts who studied the fragments believe that they could have been pieces from window panes, small bottles and vials, and simple drinking glasses. At Glasshouse Point, located one mile from the visitor center, the National Park Service exhibits the original furnace ruins. Nearby is a reconstructed glasshouse, built in the 17th century style. At the Glasshouse, costumed artisans blow and fashion glass in the 17th century manner. The handmade objects are sold at the Glasshouse.

Harrington, J. C. Glassmaking at Jamestown. Richmond: Dietz Press, 1952. Smith, Captain John. Adventures and Discourses. Detroit: Singing Tree Press, 1969.

|

Last updated: February 26, 2015